“There is no such thing as crazy.”

Psychiatrist and filmmaker Fred Miller, M.D., Ph.D., has backed this provocative catch phrase by creating an entire project around it to help young people develop healthier attitudes toward emotional problems and the treatment of mental illness.

“Having emotional problems or needing treatment for a psychiatric illness is part of being human,” he told Psychiatric News in an interview. “These are just another set of problems akin to physical maladies.”

Miller, who is chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare in Evanston, Ill., had for years been traveling to schools in the greater Chicago area to teach high school students about the symptoms of and treatments for mental illnesses and to dispel the myths about mental illness propagated by films and television.

Usually he would lecture in front of students in their health classes, but found the format less than effective. “The students' eyes would glaze over” with disinterest, he recalled.

He began thinking about more creative ways to get their attention, but it wasn't until 2003, when he was approached by the parents of a teen with bipolar disorder who committed suicide, that he moved ahead with a project he called “There Is No Such Thing as Crazy.”

The parents approached Miller because he was known for his lectures at local schools, and they wanted to discuss with him ways to reach out to other young people who had mental health problems.

He teamed up with local filmmaker John Mossman to produce a short film, titled “Five Teens' Stories,” in which five teenagers talked on camera about their experiences with mental illness, including depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Tourette's syndrome.

Miller noted that the film's five subjects were extremely candid, and the final product was a moving documentary about their experiences of struggle and healing.

In 2005, “Five Teens' Stories” won a 2005 Voice Award, sponsored by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Each year SAMHSA recognizes television and film writers and producers who have incorporated in their film scripts, programs, and productions respectful and accurate portrayals of people with mental illness.

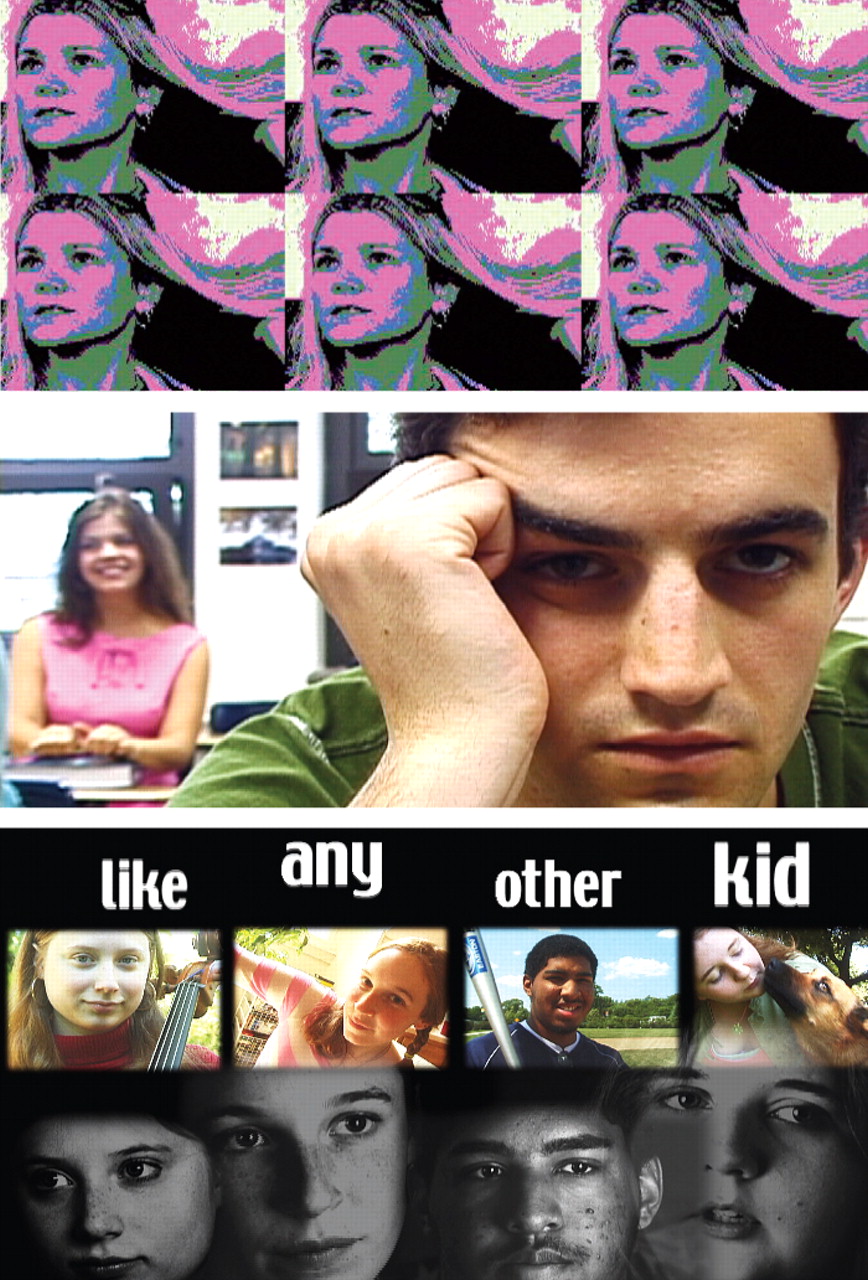

Soon after the film received national recognition by SAMHSA, the National Institutes of Health commissioned Miller to produce a film that also profiled teens with different mental illnesses. It was titled “Any Kid like Me.”

Miller then decided to turn to the Internet to broadcast his message to as many young people as possible. This endeavor led to the creation of the interactive Web site, No Such Thing as Crazy, at<www.nosuchthingascrazy.com>. The site features links to stories of teens who have experienced mental illness, facts about mental illness and treatment, and a section titled“ Living Awesomely,” which is dedicated to providing young people with tools for better mental health. Some of these tools include challenging negative thoughts in order to produce positive feelings.

“If you think you're a total loser, you will feel hopeless and depressed. If you think everything is your fault, you'll feel guilty. These global, unhelpful thoughts can be a big part of our lives,” this section of the Web site states.

The site also includes links to a number of national mental health advocacy organizations, such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health America, and books for teens and parents on mental health problems and treatments.

Also on the Web site is a message board for parents of teens with mental illness.

Miller went on to produce two additional films, “Lost and Found” and “Invasion of the Sad People.”

“Invasion of the Sad People” was the first of his films to use professional actors and animation. In “Invasion,” a high school student named Harold abandons a friend who has been unable to commit to social plans due to suffering from depression. After falling asleep, Harold dreams he is carrying the weight of depression—personified by somber people wearing black cloaks—and better understands his depressed friend when his classmates react negatively to him.

Miller said that “There Is No Such Thing as Crazy,” including the films and Web site, has been largely self-funded and that he distributes his films at no cost to those who are interested. So far, he has sent copies of his films to hundreds of individuals, schools, and community agencies.

He also has been asked to show the films at local schools and conduct discussions afterward. During the discussions, he noted, he is impressed by students' candor in sharing their experiences with emotional problems with fellow classmates and teachers.

Many teachers find the films useful because they are interested in learning to recognize the warning signs of mental illness in their students, he noted.

Looking back, Miller said that the project has enabled him to put his creative skills to work. “I have twin daughters who are filmmakers,” Miller said. “I inherited their talent—not the other way around.”

He noted that he views the project as a work in progress and is hoping to develop new ways to dispel the stigma surrounding mental illness for young people and encourage them to seek treatment when needed. Part of the project may eventually include workshops for teens and young adults, Miller said.

“I enjoy applying creativity to the destigmatization of mental illness,” Miller said.

He is now looking for psychiatrists and mental health professionals with a variety of creative talents—such as filmmakers, writers, artists, comedians, and dancers—to take the project further, he said.

The Web site “There Is No Such Thing as Crazy,” which includes information about the related films, is posted at<www.nosuchthingascrazy.com>. Copies of the films and information on getting involved in the project are available from Miller at [email protected].▪