A few years ago a dark cloud began to encroach on the pastoral landscape of Berkshire County in western Massachusetts. The abuse of opioid pain medications there was rising alarmingly, just as it was doing in cities and towns across the country.

In fact, deaths from opioid abuse there increased to the point where they surpassed the number of deaths due to suicide. This pernicious trend mirrored what was occurring in other parts of Massachusetts and in other parts of the United States.

So Berkshire Health Systems (BHS), a private, nonprofit health care organization and major provider of care in Berkshire County, decided to tackle the problem with an innovative program called the Berkshire Community Pain Management Project. The project, implemented in 2005, is an effort to improve chronic pain management while also combatting opioid abuse and diversion.

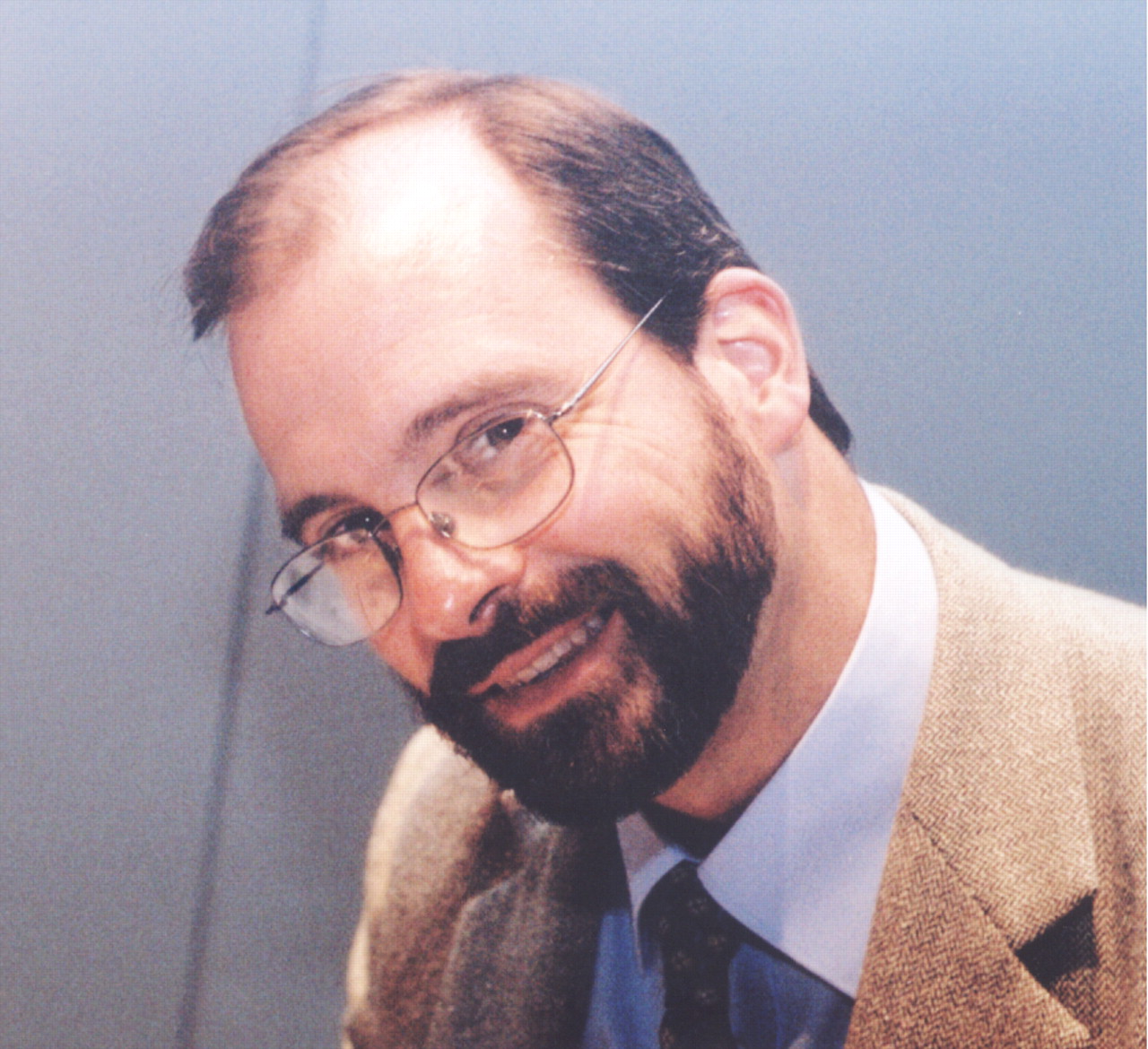

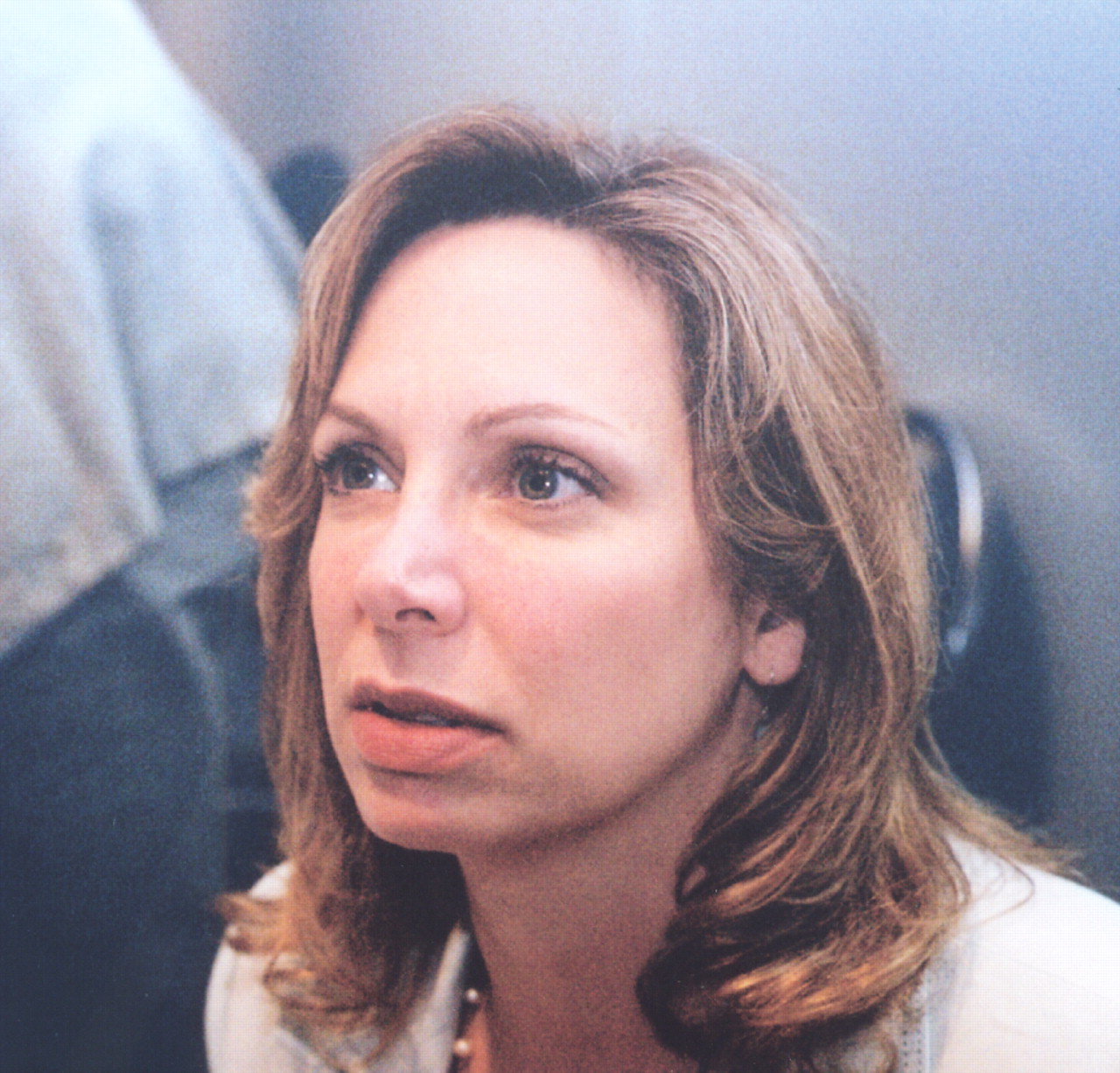

Some of the leaders of the BHS project described it in depth at APA's 2008 annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in May. They were John Rogers, J.D., vice president; Alex Sabo, M.D., chair of psychiatry; Jennifer Michaels, M.D., a substance-abuse expert; and John Harrington, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist.

Pain-Management Strategies Taught

Patients in the county who suffer from chronic pain can, for example, seek relief at a multidisciplinary clinic established as part of the project and headed by Harrington and Douglas Molin, Ph.D., a physiatrist. There, patients are assessed for pain as well as comorbidities, and a treatment plan for them is initiated. The plan consists of cognitive-behavioral therapy and exercise and may include opioids.

Harrington provides the CBT. “There is a lot of evidence that CBT can help chronic-pain patients and also some evidence that combining CBT and exercise can do so as well,” he told Psychiatric News.“ At the same time, there is little evidence that long-term use of opioids will counter pain, and substance abuse from such long-term use is a danger.”

Even though a CBT-exercise treatment regimen lasts only six weeks, it seems to be helping patients, Harrington said. To date, 41 chronic pain patients have participated. On a 0-to-10 scale, they rated their pain at 6 at the start of treatment and at 5 afterward—a statistically significant difference. The patients also experienced significantly less anxiety and depression after treatment, and their energy levels and social lives were also boosted by it, Harrington said.

The project also includes treatment for chronic-pain patients in the county who have become addicted to opioid pain medications. The major component of the treatment consists of placing patients on buprenorphine rather than on the opioid pain medications that they have been taking. The treatment is provided by Michaels.

Since buprenorphine is an opioid, it is not a cure-all for opioid dependence, she explained. Yet it does stabilize them and help reduce their craving for, and withdrawal from, the opioid pain medications they have been using. And once their craving and withdrawal have been reduced, she is better able to manage their pain. In other words, “When patients are abusing opioids such as heroin, oxycontin, Percocet, et cetera, pain management becomes difficult to impossible,” she said.

In fact, several of her patients have reported that once they switched to buprenorphine, they started receiving pain relief from aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which was not the case as long as they were taking opioid pain medications.

If buprenorphine does not reduce pain sufficiently in chronic pain patients who are opioid addicted, Michaels may refer them to Harrington for CBT and exercise as well.

“It seems these patients are doing about as well as Harrington's other pain patients, but the numbers are still too small to be sure,” she said.

Finally, another way that project staff are trying to better manage chronic pain is to promote the use of evidence-based guidelines for treatment of chronic pain. To achieve this goal, they developed a manual that includes standardized pain-assessment and pain-management tools and distributed the manual to all BHS physicians.

Efforts Under Way to Reduce Abuse

As for the team's efforts to reduce abuse of opioid medications, one such initiative requires that BHS physicians who prescribe these medications use tamper-resistant prescriptions.

Another strategy is to work with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to make data about opioid-medication prescribing in Massachusetts available to BHS physicians. The data let BHS physicians know whether their opioid-prescribing patterns are in line with those of their peers in Massachusetts. “Most physicians who may overprescribe opioids currently have no ready means of comparing their prescribing practices with those of other physicians,” Rogers said.

Electronic medical records, which are standard at BHS, are likewise being deployed to reduce opioid abuse. BHS physicians who prescribe opioids for a patient makes a special notation in the record. This way other BHS physicians will be alerted that the patient is already on opioids and will not unwittingly prescribe more than the patient needs.

Finally, pharmacists in Berkshire County are being brought on board the project to improve communication between them and BHS opioid prescribers, with the goal of identifying individuals who are trying to obtain opioid medications fraudulently. Indeed, the importance of pharmacists' cooperation cannot be overemphasized, Sabo stressed, since during 2005 they filled almost 3 million doses of Schedule II opioid medications—four times the number dispensed a decade earlier.

Moreover, because of its leadership on this issue, BHS has been selected by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to assist Brandeis University and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in testing secure electronic prescribing as a way to reduce prescription tampering and duplication and diversion of opioid pain medication.

“The challenge of a project like this is to balance a number of competing interests,” Rogers said. “If you do, you can make enormous headway.”

Since opioid abuse is rampant across the United States, Rogers, Sabo, Michaels, and Harrington believe that health care providers in other areas might want to establish a community pain-management project similar to theirs.

Indeed, Paul Cote, past commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, has called the project a “leading-edge program.” And at the APA annual meeting, Nathaniel Katz, M.D., an adjunct assistant professor in analgesic research at Tufts University and an authority on pain management, stated, “This group has really knuckled down to developing a community coalition to solve the pain management–opioid abuse problem. In my experience, their balanced and enlightened approach is unique.”

Information about BHS is posted at<www.berkshirehealthsystems.com>.▪