A failure to recognize and address the large number of suicides among elderly Americans has allowed thousands of Americans to die every year. To curb rates of suicide among older people—older white men in particular have the highest suicide rate among major U.S. demographic groups—advocates have launched an effort to force the issue onto the federal legislative agenda.

During a June briefing before congressional staff, mental health advocates, led by the Suicide Prevention Action Network (SPAN USA), discussed the scope of the problem and urged support for legislation that would bolster senior suicide-prevention efforts.

The legislation that could help reduce these suicides include companion House and Senate bills (HR 4897 and S 1854, both known as the Stop Senior Suicide Act) that would coordinate the efforts of federal agencies on the issue. The bills also would lower Medicare's out-of-pocket coinsurance rate for outpatient mental health services from 50 percent to 20 percent, a change long advocated by APA. Some of these bills' provisions also have been included in must-pass Medicare overhaul legislation (S 1715).

The high rate of suicide among senior citizens “is an issue that frequently flies under the radar,” said Yeats Conwell, M.D., a psychiatrist who has researched suicide among seniors.

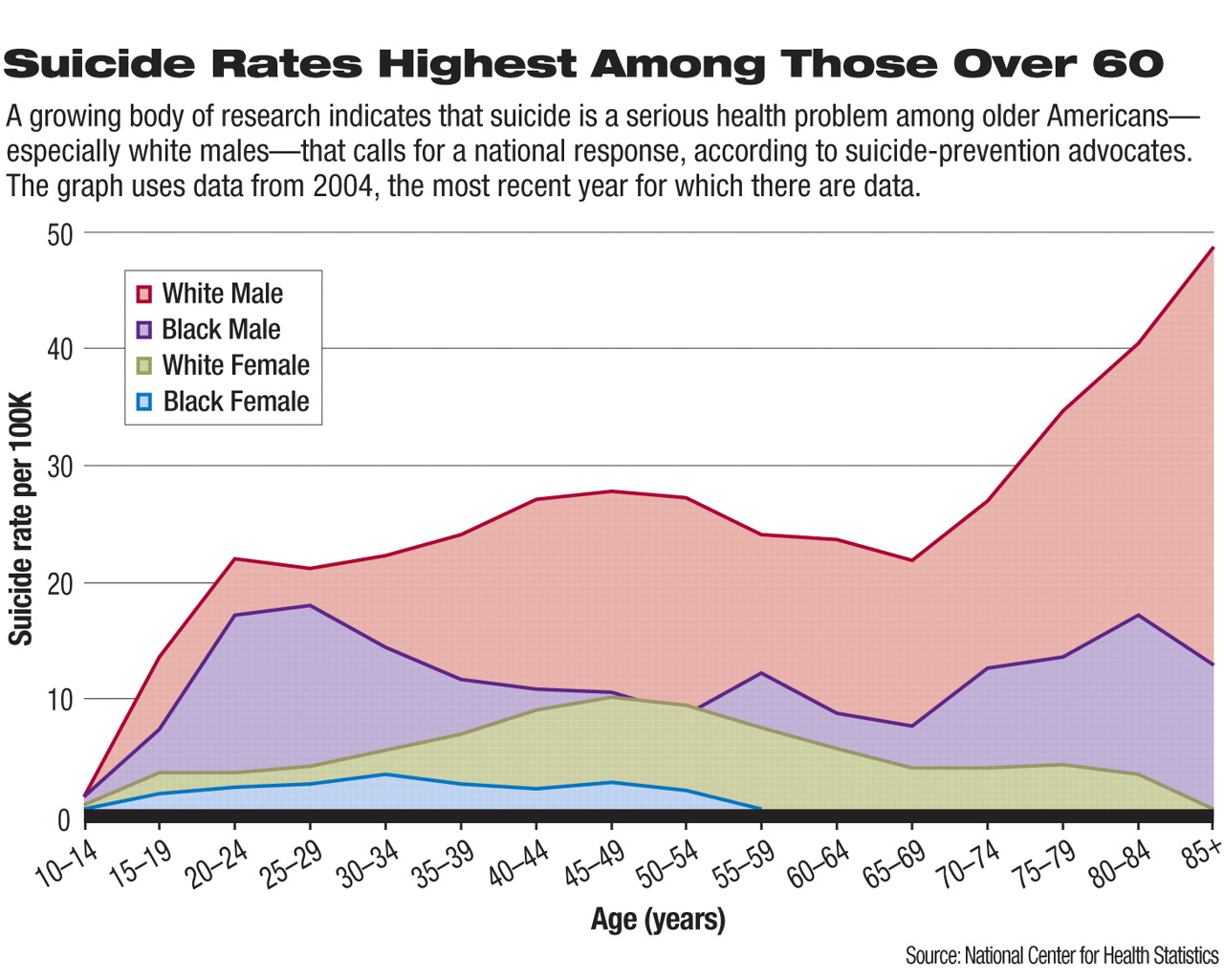

Its low profile masks the extent of the problem. There were 6,860 suicides by people older than 60 in 2004—the highest rate of suicide for any age group—according to a 2007 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People over age 60 make up 12 percent of the U.S. population, but they complete 16 percent of suicides.

The high rate of suicide among seniors, said Jerry Reed, executive director of SPAN USA, is driven by the high rate of untreated mental illness in that population. As many as 90 percent of suicides by seniors, he and other advocates noted, are likely related to untreated mental illness. “It's a very real problem,” he said.

The most recent effort to get Congress to take steps that could reduce suicide by the elderly was led, in part, by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.), who lost his father to suicide years ago.

“Clinical depression and suicidal feelings are not a normal part of aging, yet these treatable conditions are often misdiagnosed, untreated, or ignored in far too many seniors,” said Reid in a Senate floor speech when he introduced S 1854 in July 2007. “Out-of-pocket expenses under Medicare, the health insurance program for 37 million Americans aged 65 years and older, is a key reason.”

Reid and mental health advocates said the copayment difference discourages Medicare beneficiaries, especially low-income and fixed-income individuals, from seeking mental health treatment. This financial disincentive exacerbates the stigma that also keeps many seniors from seeking needed mental health care. The Medicare copay policy dates back to the inception of the program in 1965.

The Reid bill and its House version also would establish the Federal Interagency Geriatric Mental Health Planning Council. This council would coordinate suicide-prevention efforts by federal agencies that interact with older Americans.

Local Approaches Encouraged

In addition, the legislation would provide small grants to state and local governments to develop suicide-prevention strategies aimed at seniors.

Mel Kohn, M.D., Oregon's state epidemiologist, helped coordinate that state's first-in-the-nation senior suicide-prevention initiative.

“We had a youth suicide-prevention program for years in Oregon, but the data showed that we were really missing the boat on where the problems lay,” said Kohn, about the high rates of senior suicide.

The Oregon plan funded a data collection effort to understand the scope of the problem and research to find the most effective prevention approaches. As others have done, the Oregon planners found that one of the biggest missed opportunities to address suicide by seniors involved primary care physicians. Seniors have the highest rate of primary care contact of any age group, with 58 percent of seniors who commit suicide having visited their doctor within a month of their death, according to SPAN USA. Part of the effort to reduce suicide among seniors has to include education for general practitioners about the high rates of untreated mental illness among seniors and the increased risk of suicide when this population remains untreated, according to the advocates.

Prime Opportunity Awaits

Outreach and treatment especially are needed for the 1.4 million seniors who have attempted suicide and who are likely to try again, Reed said.

One-on-one intervention efforts between physicians and their patients can be supplemented by state and local governments' use of education and risk reduction plans, according to advocates. Suicide-prevention strategies among older people in other countries that have shown some promise, Conwell said, include making senior-focused telephone assistance available and reducing the availability of the most common means of suicide. For example, the most common means of suicide in Great Britain was carbon monoxide poisoning through residential gas appliances before the government mandated that domestic gas suppliers cut the carbon monoxide content in gas for household use.

Supporters said they are confident that state and local prevention strategies can be inexpensive but effective at reducing suicide rates among the older population, although research on the effectiveness of risk reduction and education plans for seniors has not yet been conducted.

The legislative outlook for the senior suicide-prevention bills is poor during the current Congress, according to congressional staff. However, some of the bills' provisions may pass as part of a Medicare overhaul, which has stalled over Republican opposition to spending increases for domestic programs.

The need for federal action on the issue will grow in the coming years, mental health advocates said, as the number of seniors is expected to grow from about 35 million now to 70 million by 2030. They plan to continue pushing Congress to act until the problem of suicide by seniors receives the federal attention it deserves.

The senior suicide prevention and Medicare overhaul bills can be accessed at<http://thomas.loc.gov> by searching on the bill numbers, S 1854, HR 4897, and S 1715.▪