Patients with acute stress disorder had fewer posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms at follow-up after a clinical trial of exposure-based therapy than did patients getting cognitive restructuring therapy or placed on a treatment waiting list, according to Australian psychologist Richard Bryant, Ph.D.

More attention in recent years to early intervention following traumatic events has increased interest in what the primary therapeutic approach should be, wrote Bryant and colleagues in the June Archives of General Psychiatry.

The researchers studied 90 patients who had experienced nonsexual assault or a motor vehicle crash and were diagnosed with acute stress disorder (ASD) from 2002 to 2006. They were randomized to receive five 90-minute sessions of either prolonged exposure therapy or cognitive restructuring therapy. A third group was placed on a wait list and told they would be reassessed after six weeks and then offered active treatment.

Prolonged exposure patients were told to “verbalize reliving the trauma experience in a vivid manner that involved all perceptual and emotional details.” They were given homework exercises. Later sessions and homework included visualizing images of trauma exposure and real-life exposure to associations with their trauma. The last session included relapse-prevention strategies to help patients damp down PTSD symptoms if they recurred.

Cognitive restructuring (CR) treatment involved identifying and monitoring maladaptive thoughts by “Socratic questioning, probabilistic reasoning, and evidence-based thinking.” Some homework and relapse prevention were included in this treatment too.

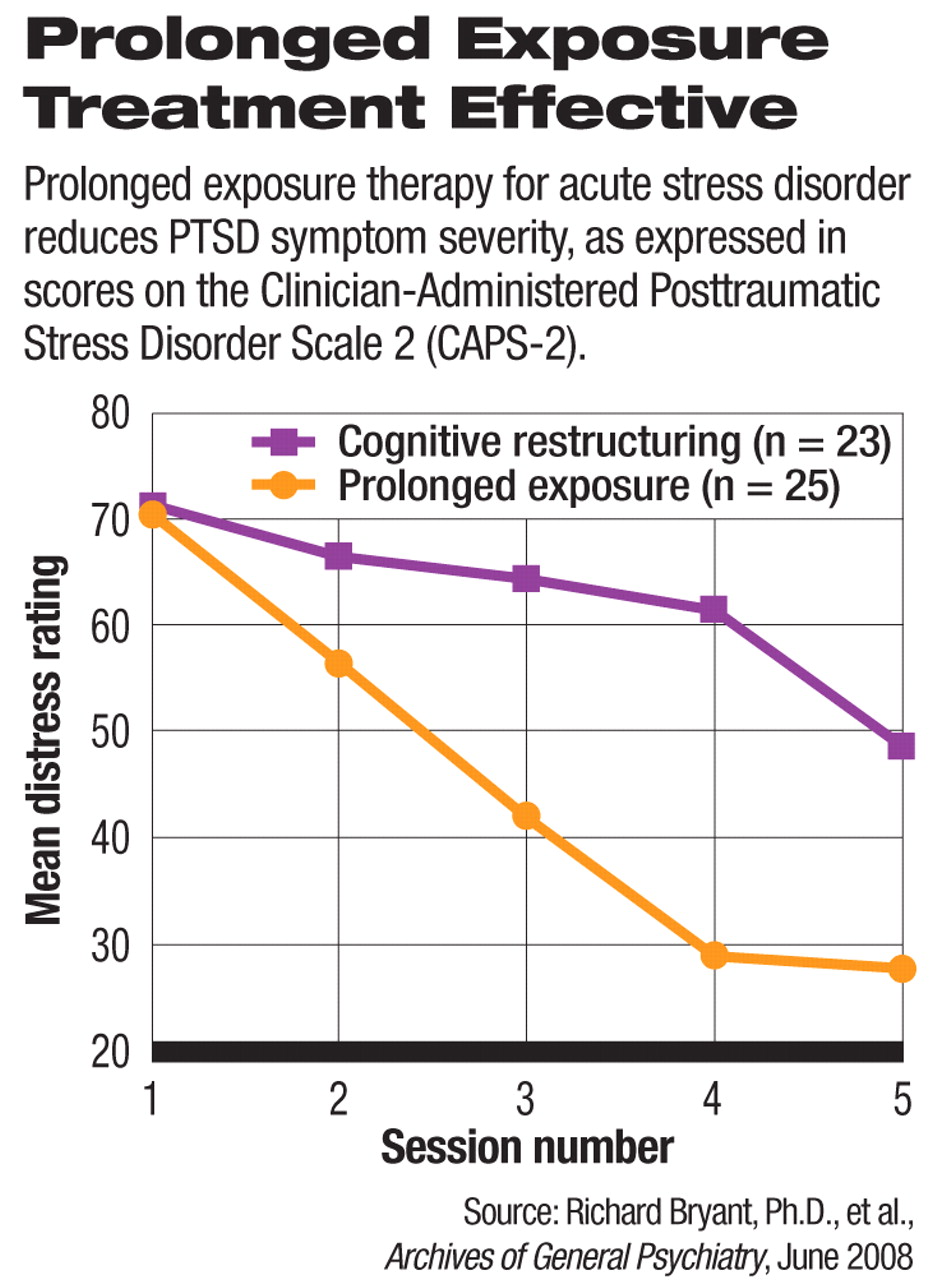

Prolonged exposure showed large effect sizes, and cognitive restructuring showed moderate effect sizes, compared with the wait-list group. After six weeks, 33 percent of the exposure group met PTSD criteria compared with 63 percent of the cognitive restructuring patients, and 77 percent of those on the wait list.

At the six-month follow-up, 37 percent of the exposure group met PTSD criteria while 63 percent of the cognitive restructuring group did. The researchers did not compare a combination of the two therapies with the single treatments.

The effect was seen early in the course of exposure treatment, even as cognitive restructuring patients continued experiencing distress.

Many therapists hesitate to use exposure therapy because it can cause distress and possibly drive patients away from therapy, according to the researchers. However, only five subjects reported adverse effects, all due to high distress, and dropped out of the study. Two subjects were in the exposure arm, and two were in the CR arm. Overall, patients getting exposure therapy reported less distress at the end of the last three sessions than did patients getting CR therapy.

“Dropout rates in the present study were comparable to dropout rates across chronic PTSD studies,” wrote Bryant and colleagues.

In a rigorous review of treatments for PTSD, the U.S. Institute of Medicine last fall said that the only treatment for PTSD supported by a strong evidence base was exposure therapy.

“The current findings suggest that direct activation of trauma memories is particularly useful for prevention of PTSD symptoms in patients with ASD,” they wrote. “[A]daptation occurs when the individual repeatedly engages with trauma reminders and learns that there is no aversive outcome.”

The study showed that not only was using prolonged exposure treatment beneficial, but also it did not result in more therapy dropouts or aversive responses than other approaches.

For Bryant and colleagues, the conclusions are clear. “[T]here is a need to better educate mental health care providers about the use of [prolonged exposure] as a frontline intervention for ASD,” they said.