In 1994 some 1,000 older Catholic priests, nuns, and brothers signed up for a mission that had nothing to do with saving souls but plenty to do with saving minds.

The mission, headed by David Bennett, M.D., director of the Rush University Alzheimer's Disease Center, was called the Rush Religious Orders Study. Subjects were evaluated medically, neurologically, cognitively, and psychologically, both at the start of the study and annually thereafter. Differences between those who develop Alzheimer's and those who do not are being analyzed to identify factors that might predict subsequent susceptibility to Alzheimer's.

During the past few years, the study has identified several putative Alzheimer's risk factors. One is rapidly progressing Parkinson's disease (Psychiatric News, June 20, 2003). Another is an enduring tendency to experience negative emotions (Psychiatric News, July 20, 2007). yet a third is depression.

And now still more results from the study, published in the April Archives of General Psychiatry, go a step further by suggesting that depression is truly a risk factor for Alzheimer's and not the result of the disease itself.

In this phase of the study, 917 subjects without Alzheimer's were evaluated annually for 13 years to determine both whether they were depressed and whether they might be developing Alzheimer's. Of the 917 subjects, 190 developed the illness during this time span. Consistent with earlier findings in this cohort, having more depressive symptoms at the start of the study was linked with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's. However, Bennett and his coworkers did not find that the subjects who developed Alzheimer's experienced an increase in depressive symptoms during the four years or so leading up to the onset of their Alzheimer's. So depressive symptoms indeed seem to be a risk factor for Alzheimer's rather than an early sign of its pathological process, Bennett and his colleagues concluded.

Yet if, as these data imply, depressive symptoms are a risk factor for Alzheimer's, how might they be contributing to the risk? Since major depression has been linked with brain atrophy, such atrophy in turn might make the brain more susceptible to Alzheimer's, Bennett and his team speculated. Understanding the means by which depression preps the brain for Alzheimer's might lead to some way of preventing Alzheimer's, they suggested.

Meanwhile, two other groups of scientists have been looking into whether nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) might do so.

In the first study, Steven Vlad, M.D., of Boston University and coworkers evaluated prescription NSAID use by some 49,000 veterans who had developed Alzheimer's and by some 197,000 veterans who had not. The NSAID classes assessed included arylpropionic acids such as ibuprofen or naproxen, enolic acids such as piroxicam, COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib, nonacetylated salicylates such as salsalate, and high-dose aspirin.

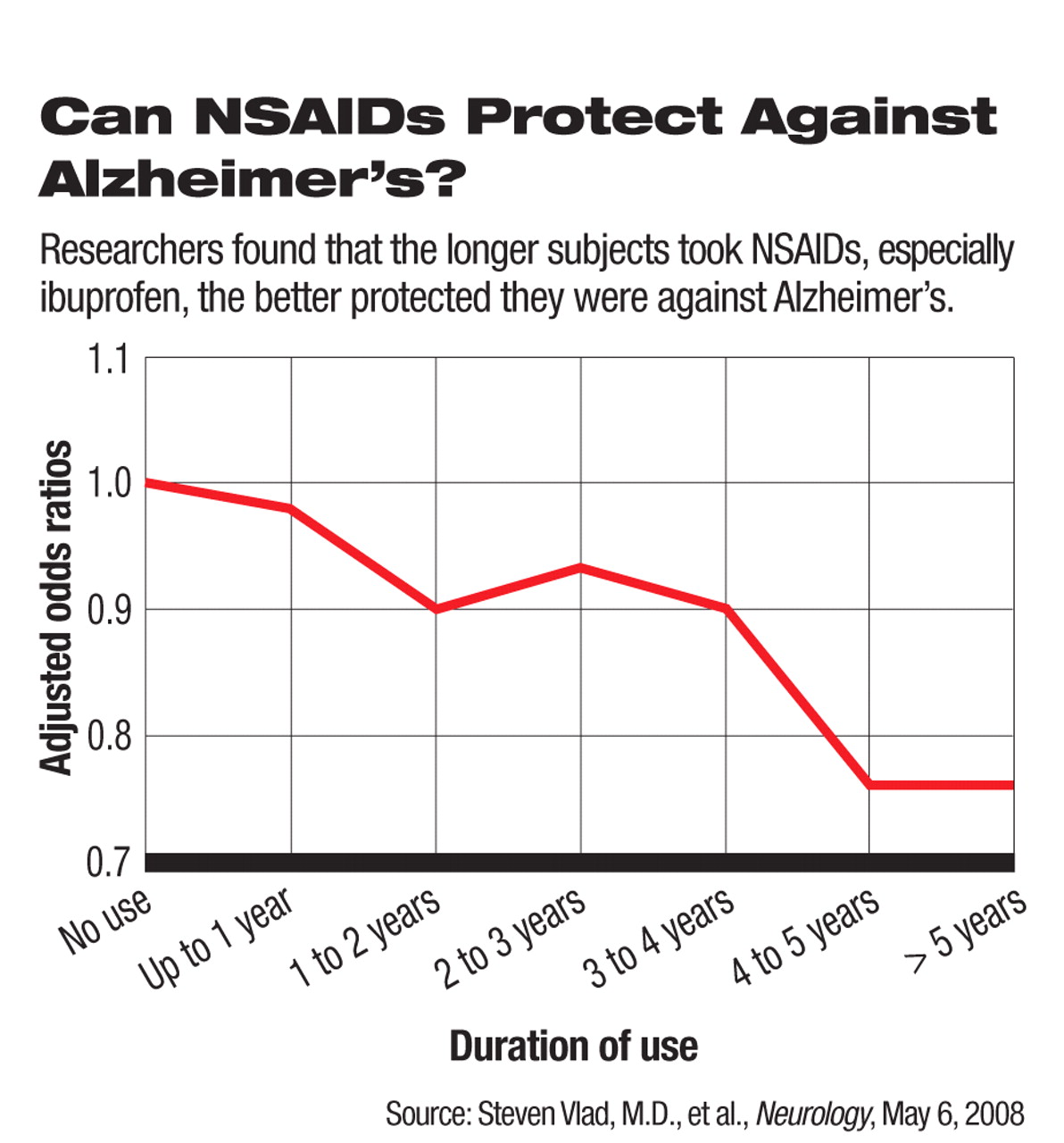

The researchers found that the odds of developing Alzheimer's decreased with longer NSAID use. Compared with persons not using NSAIDs, the odds of getting Alzheimer's decreased from 0.98 among those with use for one year or less to 0.76 for those using NSAIDs for more than five years. However, the researchers found that the protective effect did not seem to be identical for each NSAID. Some, such as ibuprofen, showed clear protective effects; others, such as the COX-2 inhibitors, did not, and in yet others the effect on Alzheimer's risk was unclear. The results appeared in the May 6 Neurology.

In the second study, Barbara Martin, Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University and her colleagues allocated some 2,100 subjects aged 70 years or older and with a family history of Alzheimer's to one of three treatment arms—200 mg of celecoxib twice daily, 220 mg of naproxen twice daily, or a placebo. The researchers followed the subjects for three years to see whether those getting either celecoxib or naproxen were better protected against Alzheimer's than those getting a placebo.

The answer was no, the researchers found. In fact, there was weak evidence that the cognitive function of the naproxen group was inferior to that of the placebo group. Thus, neither celecoxib nor naproxen appears to shield people against Alzheimer's, Martin and her group concluded in their study report, which was posted May 12 on the Archives of Neurology Web site.

All three studies were financed by the National Institutes of Health.