Buprenorphine effectively prolongs abstinence and prevents relapse in the long-term maintenance treatment of heroin-dependent patients, researchers have found in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and conducted at an outpatient research clinic in Muar, Malaysia, between July 2003 and May 2004. The results were published in the June 27 The Lancet.

After completing a two-week residential detoxification program at baseline, 126 patients with a

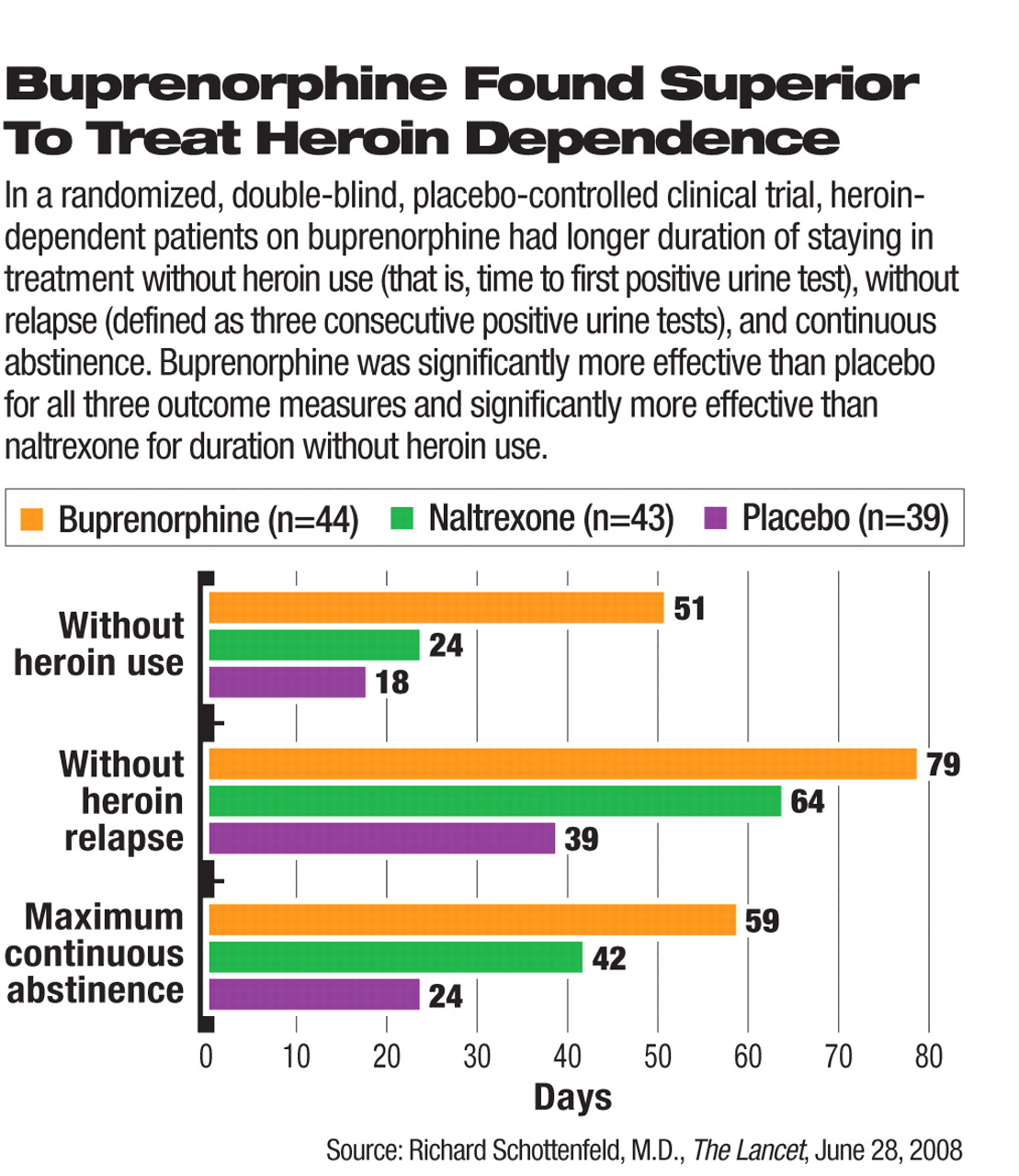

DSM-IV diagnosis of heroin dependence were randomly assigned to one of three arms of treatment—oral buprenorphine (n=44), naltrexone (n=43), or placebo (n=39) for 24 weeks. Those treated with buprenorphine had significantly longer duration of abstinence before the first heroin use (positive urine test) and duration to heroin-related relapse (three consecutive opioid-positive urine tests) than those who received naltrexone or placebo (see

chart). The buprenorphine-treated group also had significantly better outcome than the placebo group in the maximum number of consecutive days of abstinence.

All patients in the study also attended weekly sessions of individual and group counseling, which included education and training on preventing relapse and reducing risky behaviors linked with HIV transmission. All patients were given urine drug tests three times a week.

The participants in each treatment group had been using heroin for an average of 14.5 to 16.4 years. Three quarters or more of the participants in each group had used injected drugs.

Retention is critical to the success of substance-dependence treatment. At the end of the six months, 36, 29, and 23 patients in the buprenorphine, naltrexone, and placebo groups, respectively, remained in the treatment. The retention rate in the buprenorphine group was higher than either the naltrexone or placebo group; however, the rate did not differ significantly between the naltrexone and placebo groups.

“This is the first randomized study, to our knowledge, that directly compares an [opioid receptor] agonist with the antagonist naltrexone,” Richard Schottenfeld, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine and the lead author of this study, commented to Psychiatric News. He noted that the study revealed a consistent pattern in all of the efficacy indicators: “The buprenorphine group did the best, the placebo group the worst, and naltrexone in the middle.”

In Malaysia, injected heroin abuse and associated HIV transmission pose a significant public health problem. This study was undertaken as a part of NIDA's international collaborative program that supports research in regions with drug-related HIV/AIDS epidemics.

The authors of the study examined the effects of these treatments on self-reported HIV high-risk behaviors and found that these behaviors decreased significantly from baseline in all three groups, and the difference was not significant among the groups.

“Heroin addiction is a very big problem and a major driver of HIV/AIDS epidemic in that region of the world,” Schottenfeld said.“ The government had been very resistant to medical treatment for drug addiction until the 1990s.” The past decade saw a gradual shift in the attitude of authorities, from locking up addicts in jail and detoxification facilities to long-term maintenance medical treatment for substance dependence and abuse.

The authorities in Malaysia and many other countries have considered opioid agonists, such as buprenorphine and methadone, as a substitute addiction rather than an effective treatment.

“Stigma is what's underlying a lot of the resistance to agonist maintenance treatment,” according to Schottenfeld. He said the Malaysian authorities were initially opposed to the use of any opioid agonist. However, this research and other objective evidence of the effectiveness of buprenorphine have had a significant influence on the public health policies in Malaysia. Recently, the country expanded approved treatment options to include methadone.

“The use of oral naltrexone is often an indicator of moral disapproval of substitution treatments with opioid agonists because they stabilize addicts rather than attempt to produce abstinence,” wrote University of Queensland's Wayne Hall, Ph.D., and Richard Mattick, Ph.D., in an accompanying editorial. The two researchers, who work at the university's School of Population Health, recommended that “health authorities in developing countries should no longer restrict pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence to oral naltrexone.... The preferred oral pharmacological treatment for opioid dependence should be agonist maintenance with either methadone or buprenorphine.”

In the United States, buprenorphine with and without naltrexone is approved to treat opioid dependence. However, the stigma of and barriers to opioid agonist treatment remain in place in the United States as they do abroad, Schottenfeld pointed out. “Agonist maintenance treatments aren't as widely available as they should be. Many heroin-dependent patients do not have access to effective buprenorphine or methadone treatment.”

Treatment-oriented policies are gaining ground in some countries. Schottenfeld noted that several similar NIDA research programs are currently being conducted in China and Iran and that there is a shift in many countries toward increased recognition of the need for long-term medical treatment for substance dependence as for any other chronic diseases.

An abstract of “Maintenance Treatment With Buprenorphine and Naltrexone for Heroin Dependence in Malaysia...” is posted at<www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS014067360860954X/abstract>.▪