Although a variety of universal health care proposals has been bandied about in Washington, D.C., in recent years (see

Senator Says Health Reform to Come in Baby Steps), some experts are now wondering if a long-existing plan might work—at least for the uninsured.

The use of Medicaid to cover most, if not all, of the nation's 47 million uninsured people has begun to be discussed broadly by health-policy experts as one of the most realistic options.

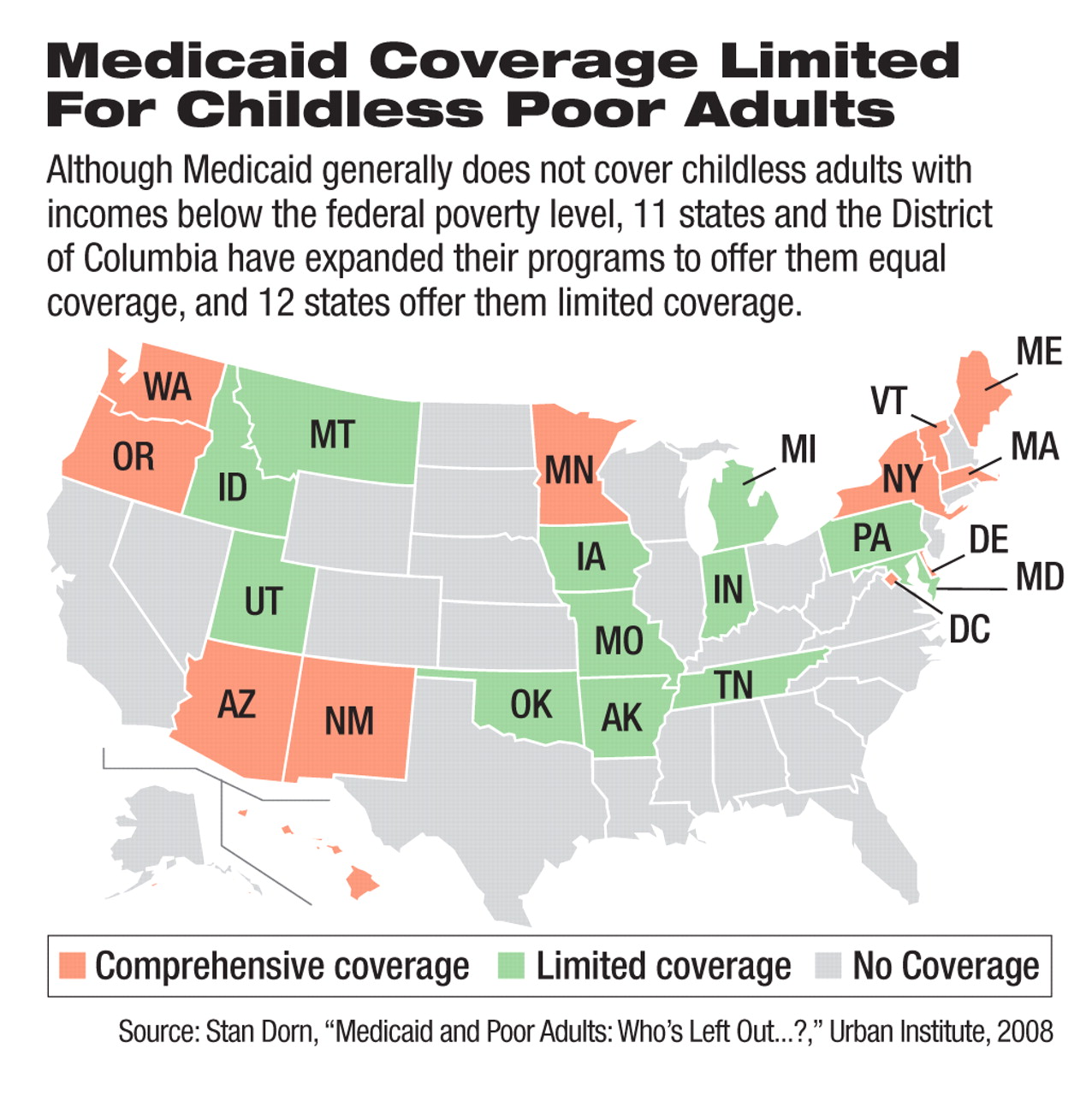

Consideration of an expanded role for Medicaid fits with the popular but mistaken belief that all low-income people are qualified for coverage under the program. Medicaid eligibility is currently limited to low-income children and adults who fall into one of nearly 50 categories of eligibility, such as pregnant women.

“It's not enough to be poor” to be eligible for Medicaid, said Stan Dorn, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, at a September health-policy forum in Washington, D.C., about Medicaid eligibility.“ You also have to fit into a federally defined eligibility category.”

Medicaid's design leaves out most low-income adults who are childless and those whose children have reached adulthood. Research that Dorn has conducted shows that such low-income adults are by far the largest group of uninsured Americans. He found that 55 percent of low-income people who are uninsured are adults who do not qualify for Medicaid.

“So if you're serious about doing something about the uninsured and about those who lack the ability to provide for themselves, this is a group of people you need to take very seriously,” Dorn said.

Also among those who are uninsured and ineligible for Medicaid are nearly 16 million adults aged 18 to 64 who have at least one chronic illness requiring continuing care to prevent expensive medical crises.

These individuals have caught the attention and support of most Americans, according to mutliple polls. In one of those polls, 83 percent of respondents said they believe that “immediate action” is required by the next president and Congress to address coverage for the uninsured, according to Gary Ferguson, senior vice president of American Viewpoint Inc., a political polling firm.

And using Medicaid to cover low-income, uninsured individuals appears popular. Ferguson's polling found that 68 percent of Americans favor expanding Medicaid to cover more of those with lower incomes, while only 28 percent opposed such a move.

Then again, such support for Medicaid is tempered by strong reservations about the potentially high costs of a large Medicaid expansion.

Is Medicaid Role Practical?

The public support for a possible Medicaid role in filling the insurance-coverage gap has led more health-policy experts to focus on the practicality of such a role for Medicaid. Recent expansions in some states' Medicaid programs and other public-health programs have been credited with the 1.3 million-person drop in the number of uninsured from 2006 to 2007.

Medicaid has several advantages that argue for its use in helping to reverse the nation's uninsured rates, according to Barbara Coulter Edwards, a principal with Health Management Associates, a firm that operates hospitals. Unlike any new program that might be created to cover the uninsured, Medicaid has existing networks, low administrative overhead, and existing relationships with private health plans through its managed care plans, and it partners with federal and state governments through its dual-funding structure.

Several specific approaches to a greater Medicaid role have been suggested, although none of them specifically delves into the mental health components of Medicaid—the nation's largest public payer of psychiatric care.

Ending Budget Neutrality Suggested

One approach would scrap the requirement for budget neutrality in the waiver requests through which states apply for permission from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to alter their Medicaid programs. The chief problem of this approach is that federal budget officials in any presidential administration could balk at the elimination of, or great reductions in, budget-neutrality requirements, according to Dorn.

Another approach would make Medicaid an income-based program that covers every uninsured person whose annual income is under a certain amount. This approach could produce huge savings because much of the administrative costs of determining eligibility under current complex categorizations would be scrapped for simpler income verification.

“Of course the big disadvantage of this approach is that lots of folks who qualify for Medicaid today would lose coverage,” Dorn said. For example, some beneficiaries in nursing homes receive other federal benefits that could push them over the income limits.

A third approach to expanding Medicaid would create a new eligibility category for low-income adults without regard to other characteristics. This approach would help the poorest uninsured adults, while not taking coverage from people who have it today, according to Dorn.

Some have voiced caution, however, in using Medicaid expansions to cover uninsured people.

Nina Owcharenko, a senior policy analyst for health care at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, said that such expansions would add to Medicaid's already ballooning price tag, which cost state and federal governments about $338 billion in 2007 and is expected to reach $717 billion in 2017. This growth threatens to consume state budgets, which already earmark an average of 22 percent of funds for Medicaid.

“You've got to wonder if it's crowding out other state priorities [such as] transportation, criminal justice, education, and a lot of other issues that are of concern to people at the state level,” said Owcharenko.

Another problem that proponents of a Medicaid expansion face is whether states can commit to covering large numbers of additional uninsured people when they repeatedly demonstrate difficulty in maintaining previous coverage commitments when state tax revenues drop.

“Medicaid is counter cyclical, so just when the economy is at its worst, and the state is least able to pay, the demand for the program is the greatest,” said Edwards, former acting director of the National Association of State Medicaid Directors.