Most veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are prescribed psychotropic medications, but the percentage decreases as they get older, according to Department of Veterans Affairs' researchers.

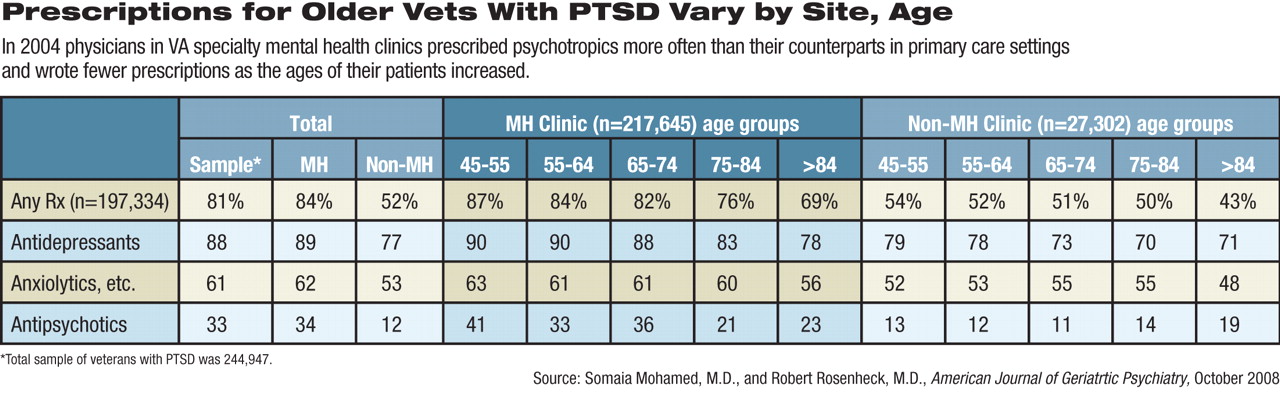

Their study included 274,297 veterans in the VA health system diagnosed with PTSD. About 80 percent of them received prescriptions for a psychiatric drug in 2004, the year covered by the study. Of those, 89 percent got prescriptions for antidepressants, 61 percent for anxiolytics/sedatives-hypnotics, and 34 percent for antipsychotics. Similar prescription percentages applied to veterans older than age 45 (n=244,947) within the larger cohort, wrote Somaia Mohamed, M.D., an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, and Robert Rosenheck, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and public health at Yale. Rosenheck is director and Mohamed is associate director of the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven, Conn.

Their research appeared in the October American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Mohamed and Rosenheck used national administrative databases from the VA as their source. The pharmacy data became available to health services researchers at the VA only in recent years. The study measured only prescription data, not outcomes.

Prescribing rates were lower for patients seen in primary care (52 percent overall) compared with those seen in specialty mental health clinics (84 percent). Patients seen in mental health clinics may be sicker and have more comorbidities than those seen in primary care settings, possibly accounting for the higher number of prescriptions.

Prescribing rates dropped as the ages of the veterans increased (see table). For instance, compared with 45- to 54-year-olds, those aged 75 to 84 were 46 percent less likely to receive a psychotropic prescription. There might be several explanations for this effect, said Mohamed and Rosenheck. For one thing, increasing medical comorbidities that appear with age may lead physicians to be more cautious about prescribing another drug to an elderly patient already using several medications.

Intensity of PTSD symptoms may also recede with age, according to previous research cited by Mohamed and Rosenheck.

“Older veterans may [also] be reluctant to take medications because they experience mental illness as more stigmatizing than younger veterans,” the researchers noted, referring to World War II and Korean War veterans.

The strongest predictor for prescription of antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives-hypnotics, or antipsychotics was a diagnosis of an indicated illness for which these medications have been approved. However, choice of treatment is often based on symptoms rather than diagnoses, said Mohamed and Rosenheck in an interview.

“Many people who get antipsychotics don't have these disorders,” said Rosenheck. “That's not surprising in itself, but in this study we have documented the magnitude of the practice.”

Off-label use is rational, said Rosenheck, but there is little systematic research on such use.

“The FDA has left it up to industry, but industry funds studies for expanding indications for use,” he said. “More research on drugs assessing their value in treating symptoms, whether or not they arise as part of a diagnosis, might provide a better evidence base for use of these drugs.”

An abstract of “Pharmacotherapy for Older Veterans Diagnosed With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans Administration” is posted at<http://ajgponline.org/cgi/content/abstract/16/10/804>. A related abstract is posted at<www.psychiatrist.com/abstracts/abstracts.asp?abstract=200806/060811.htm>.▪