The most important finding in all trauma studies is that the more intense the traumatic experience, the higher the prevalence of psychiatric problems, according to Robert Ursano, M.D., professor and chair of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

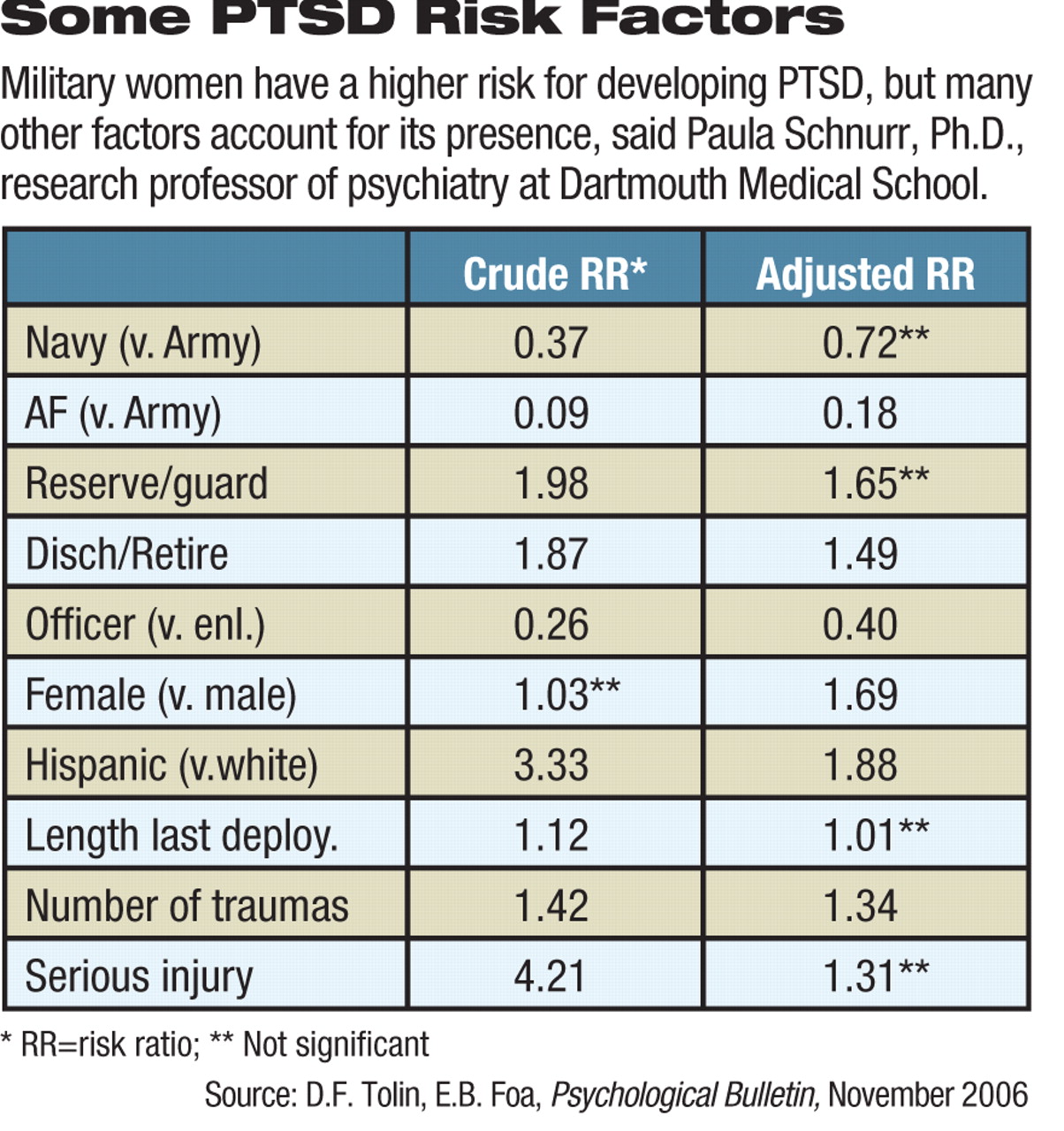

Nevertheless, other factors may be related to the presence or severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other trauma responses. Race or gender may play roles, but so can the victim's trauma history, the type of stressor, the surrounding social response from family or community, ethnocultural differences in the expression of distress, and stressful posttrauma events like divorce, unemployment, lack of treatment, and negative experiences.

Often, risk factors that seem clear at first can lose significance when controlled for statistically. For instance, black soldiers in the Vietnam War experienced higher combat exposure than other soldiers, which appeared to explain their higher incidence of PTSD. Hispanic soldiers not only saw more combat, but also were younger and had lower educational attainment than their non-Hispanic peers, which explained their increased risk, said Ursano. He made his remarks at a conference in October on trauma spectrum disorders cosponsored by the Department of Defense's Defense Centers of Excellence of Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“As Einstein said, you have to look below the variable to see what is really represented,” said Ursano.

To cite another example, initial data from Sandro Galea's studies of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York showed that Hispanics had a 1.74 increased risk of PTSD compared with other ethnic groups, but looking below the variable revealed that only Puerto Ricans (odds ratio 2.79) and Dominicans (odds ratio 3.08) had a higher risk beneath the broader Hispanic umbrella, said another speaker, Paula Schnurr, Ph.D., a research professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School.

Thus, the apparent role of the original overarching ethnic term was diminished once adjustment was made for other factors like income, age, or losing a loved one in the attacks, she said.

Thus, terms like “race” and “ethnicity” must be carefully defined and, once subdivided appropriately, may reduce statistical power for some comparisons, said Schnurr.

“There is further confusion about causality,” she said. She characterized a “risk factor” as a statistical association—causal or not—with an injury or disease, but a“ risk marker” as a form of risk factor that is not causal.

“Sociodemographic characteristics are risk markers,” she emphasized. “They predict, but do not explain, why some sociodemographic groups differ in risk of PTSD.”

For example, studies show that women are at greater risk for developing PTSD but that men are at greater risk for exposure to trauma. Controlling for likelihood or type of exposure does not explain all the difference, she said.

“We need new data and new analysis to find out more about how sociodemographics relate to PTSD,” she said. “We have to avoid misleading heterogeneous groupings like black versus white, avoid stigmatizing certain groups, and look at potential mediators. We also need to apply the information we already have to modify risk and explore other posttraumatic stress reactions other than PTSD.”

Factors such as severity or age at exposure, coping abilities, appraisal of the event, or biological responses like HPA axis sensitivity have been hypothesized as playing roles as well, she said.

Schnurr also noted that the timing and duration of a PTSD diagnosis often seem unclear in some research. Both researchers and diagnosticians should differentiate between comparisons involving the development of PTSD (ever having it vs. never having it) and the maintenance of the diagnosis (current vs. past PTSD).

Recognition and treatment of PTSD are low, said epidemiologist Kathryn Magruder, M.P.H., Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Only 7 percent of persons with PTSD made a treatment contact in the first year of onset, and there is a median 12-year delay in seeking treatment.

There are no evident gender differences in these rates, but African Americans are half as likely to have a lifetime treatment contact, said Magruder. Among military populations, studies showed that 80 percent of respondents returning from war-zone deployment acknowledge a mental health problem, but less than half (23 percent to 40 percent) sought any help. Among VA primary care patients, only 48 percent of persons meeting criteria for PTSD had a notation in their charts regarding the disorder.

“This indicates a lack of recognition of PTSD and also poor recognition of multiple diagnoses by primary care doctors,” said Magruder.

The number of disability applications is increasing among all eras of veterans, including World War II veterans, but most applications are being filed by Vietnam-era vets, said Magruder.

In the future, the VA system must be redesigned to accommodate more women and younger veterans, while answering the questions raised by psychiatric epidemiology, she said.

“What accounts for that 12-year delay? Can screening for PTSD reduce delays? Do all who screen positive need treatment? Does earlier treatment improve outcomes? Can we improve access and outcomes by adapting treatment to be delivered in primary care?”

One advantage for clinicians and patients today is that the presence of psychological problems induced by the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have been acknowledged and studied in the midst of the conflicts.

“The first request for applications for the treatment of psychiatric casualties of the war in Vietnam were issued in 1979, six years after the American combat involvement in the war ended,” said Terence Keane, Ph.D., chief of psychology service at the VA Boston Healthcare System and director of the Behavioral Science Division of the National Center for PTSD.“ The work by Charles Hoge and colleagues at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research is giving us real-time data on the consequences of an ongoing war and permits surveillance and care for troops with unprecedented speed and rapidity.”

Still, said Keane, the Pentagon and the VA are now challenged by a constellation of problems in the population of service members returning from combat—PTSD, traumatic brain injury, chronic pain—that has not been previously addressed collectively in the literature. Primary care will not have the capacity to treat all people with psychological problems, he said. Only an integrated approach to care will help these individuals.

The Web site of the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury is<www.dcoe.health.mil/>.▪