The Kimberley region of Western Australia is a land of vast and spectacular natural beauty—ochre rock landscapes, plunging waterfalls, beaches fronting the turbulent Indian Ocean. It is also home to a number of Australia's indigenous people, collectively called Aborigines.

Yet in spite of the exquisite terrain, life for many of them is far from ideal. Their physical health tends to be dismal. And they have now been found to possess what may be the highest dementia rate in the world.

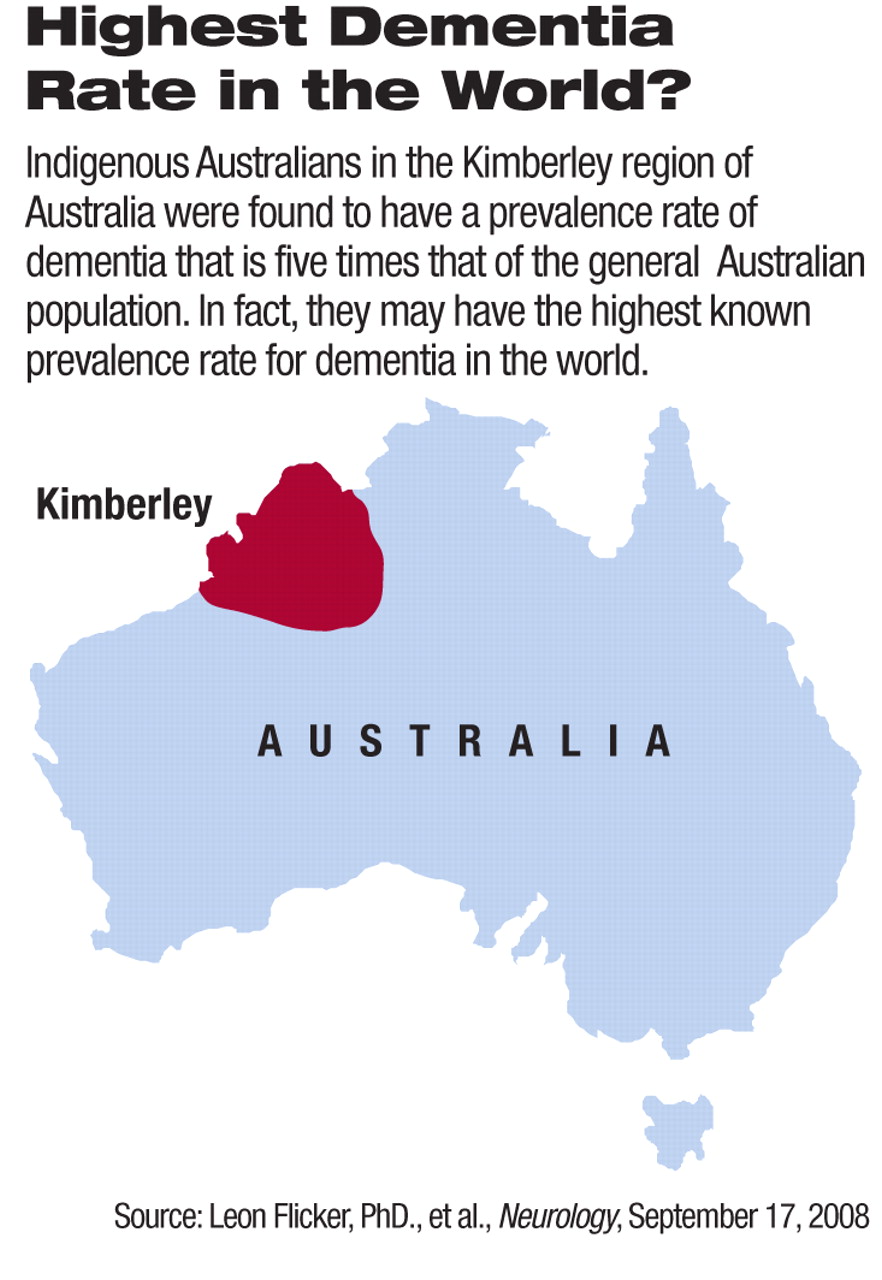

Specifically, Australian scientists have now found, after assessing 365 indigenous persons in the Kimberley region who were aged 45 or older, that this population has a prevalence rate of dementia five times higher than that of the general Australian population of comparable age—or 12.4 percent versus 2.4 percent, the latter rate of which is similar to that in other developed countries. Results were published online September 17 in Neurology.

In fact, the prevalence rate of dementia among the subjects aged 60 or older was 24 percent—perhaps the highest known prevalence rate for dementia in the world, according to the scientists. They noted that the only known prevalence rate that comes close was an Alzheimer's disease prevalence rate of 21 percent reported for an elderly Arab community in Israel.

“We were surprised by these results,” the lead investigator of this study, Leon Flicker, Ph.D., a professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Western Australia in Perth, told Psychiatric News.“ It was previously thought that because of the high mortality in the indigenous Australian population, older people were sparse, and dementia was uncommon. But despite there having been lower numbers of older people, we found very high rates of dementia, particularly in younger people.”

The reason for this dementia “epidemic,” Flicker speculated, may be because indigenous Australians in the Kimberley region possess a number of characteristics that in turn predispose them to dementia. For example, he and his colleagues found that 60 percent of subjects over age 45 had no formal education, 51 percent had experienced head injuries, 50 percent had poor mobility, 43 percent had high blood pressure, and 42 percent had diabetes.

Flicker and his colleagues are now exploring ways whereby they can improve both the mental and physical health of these individuals. For example, if they could get the people to exercise more, it might not just benefit their physical health, but reduce their risk of dementia.

Indeed, Flicker and his colleagues found in another recent study, which they conducted in nonindigenous Australians, that exercise can improve cognitive function in older adults at risk of dementia; that is, exercise is beneficial in persons over age 50 who complain of mild memory problems. True, many observational studies have already found that people who are physically active seem less likely than sedentary persons to experience cognitive decline and dementia in later life. But this study of 170 subjects, reported in the September 3 Journal of the American Medical Association, appears to be the first randomized, controlled trial to do so, according to Flicker and his group.

Both studies were funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

An abstract of “High Prevalence of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment in Indigenous Australians” is posted at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/01.wnl.0000320508.11013.4fv1>. An abstract of “Effect of Physical Activity on Cognitive Function in Older Adults at Risk for Alzheimer's Disease” is posted at<http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/300/9/1027>.▪