An interactive self-help program may serve as an artificial counselor to help astronauts solve psychological and interpersonal problems during prolonged space flights or extended stays in a space station.

This self-guided, multimedia computer program is intended to treat depression using an established behavioral-treatment approach known as problem-solving therapy, which is widely used in psychotherapy in primary care settings, James Cartreine, Ph.D., the principal investigator on this project, told Psychiatric News.

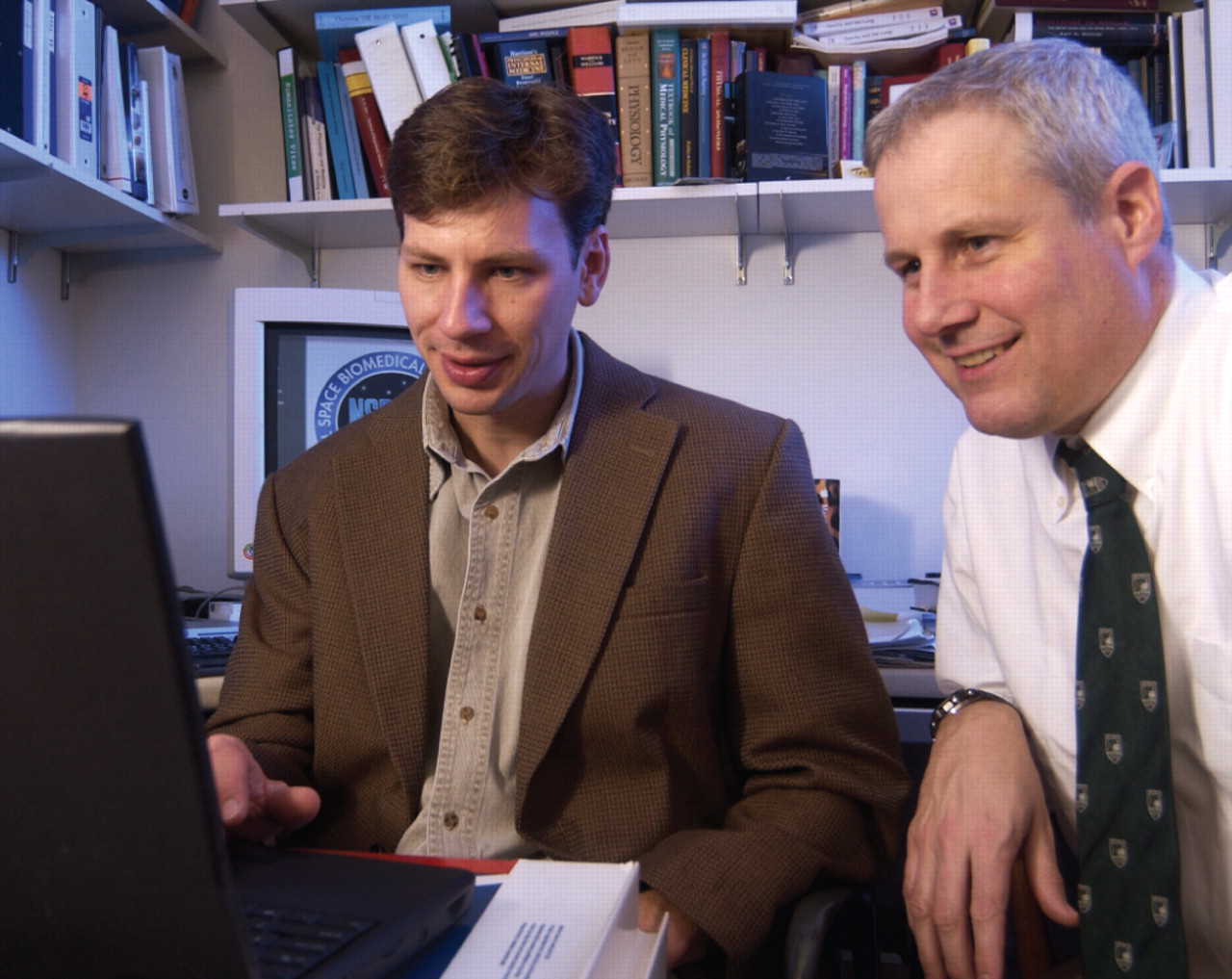

The user is guided through the program's series of steps by the prerecorded voice and image of a psychologist (in this case, Mark Hegel, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School).

First, the user is instructed to make a list of concrete, measurable, objective problems being experienced that exacerbate his or her low mood and can directly be addressed by new behaviors such as regular exercise or increased interpersonal interactions. Second, the user is asked to choose one problem from the list that has a reasonable likelihood of being solved and to then devise a clear and specific goal that marks the ultimate solution of the problem. The user is encouraged to brainstorm different ideas to come up with many possible ways to reach the solution of the problem and, with the help of the computer, chooses the action that is most likely to solve the problem.

“This is a step-by-step, structured process, which lends itself to a computerized approach,” said Cartreine, a psychologist in the Division of Clinical Informatics at Boston's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.“ The computer program is like an interactive workbook to help the user solve problems.” He noted that the computer program does not solve the problems for the user, but rather facilitates an individual's own problem-solving behaviors, thus mimicking the strategy of a live therapist in one-on-one sessions.

The program uses the validated nine-item depression scale in the Patient Health Questionnaire, known as the PHQ-9, to assess the severity of the user's depression symptoms at baseline and track clinical progress over time.

The self-guided treatment program is one module of a suite of programs known as the Virtual Space Station. It was developed for NASA and funded by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, a consortium of organizations and institutions devoted to researching health risks in long-duration space flights. Two additional modules for managing interpersonal conflicts and self-treatment for anxiety and stress are in development.

Astronauts are screened for physical and mental health and are generally less vulnerable to illnesses than the average person. But long space flights pose unique challenges to even an otherwise tough person, Jay Buckey, M.D., a professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School and a co-investigator on the project, told Psychiatric News. He was an astronaut at NASA in the 1990s and flew on a 16-day mission aboard the Columbia space shuttle in 1998.

Many astronauts, however, participate in missions that are much longer than Buckey's. For example, a stint on board an international space station usually lasts four to six months, which could be psychologically challenging.

“On a long flight, if the mission isn't going well, and the crew is in conflict, and no one is getting enough sleep, you can imagine that may be a situation where depression could develop,” Buckey said. The isolation and stress may have a significant impact on astronauts' mental health.

The depression self-treatment program has been tried by several researchers stationed in Antarctica, where the isolated condition mimics that of long space flight. A randomized clinical trial of the program, led by Cartreine, was slated to begin in October at Beth Israel Deaconess and would assess the program's effectiveness in 100 volunteers with mild to moderate depression.

Both Cartreine and Buckey noted that this self-treatment program may be useful for not only astronauts but also the general patient population, and that NASA is interested in spinning off its technology for civilian use.

“It does not replace a psychologist or a psychiatrist,” said Buckey. “But it can guide the user to identify [his or her] problems” and then provide instructions on how the user can take steps to solve those problems. “Even people who are not depressed can find it helpful,” he said. Cartreine added that it also can be used in conjunction with in-person therapies and medications.

“The field of computer-based psychotherapy is still very new,” Cartreine noted. “Research has shown that people are more willing to admit embarrassing problems to a computer than to a live person—[problems] such as suicidal or homicidal ideations, certain sexual behaviors, and addictions.” In other words, he said, a computer is often perceived in patient interviews as being less judgmental than a live person.

A description of the Self-Guided Depression Treatment on Long-Duration Spaceflights is posted at<www.nsbri.org/Research/Projects/viewsummary.epl?pid=155>.▪