Just as negative psychological states seem to be toxic to the human heart, positive ones seem to be beneficial. For instance, optimism has been linked to reduced progression of hardening of the arteries. Those scoring high on forgiveness measures exhibited less cardiovascular reactivity to acute stresses.

And now emotional vitality—a positive state associated with interest, enthusiasm, excitement, and energy for living—is associated with cardiovascular health as well, a new study has found. The study was conducted by Laura Kubzansky, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Harvard School of Public Health, and Rebecca Thurston, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. Results appeared in the December 2007 Archives of General Psychiatry.

The study included a nationally representative sample of about 6,000 American men and women. Its goal was to evaluate the hypothesis that emotional vitality is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease. None of the subjects, during medical exams at the start of the study, showed signs of coronary heart disease.

Each subject completed the General Well-Being Schedule, a validated measure that is commonly used in health research and that contains six subscales dealing with depressed mood, anxiety, general health, vitality, emotional self-control, and a sense of positive well-being. Questions refer to how respondents have been feeling during the prior month. The researchers then used the questions having to do with emotional vitality—say, how much energy or pep do you have, how happy are you with your life, is your daily life full of things that interest you—to derive an emotional-vitality score for each subject. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 35. Subjects' average score was 25.

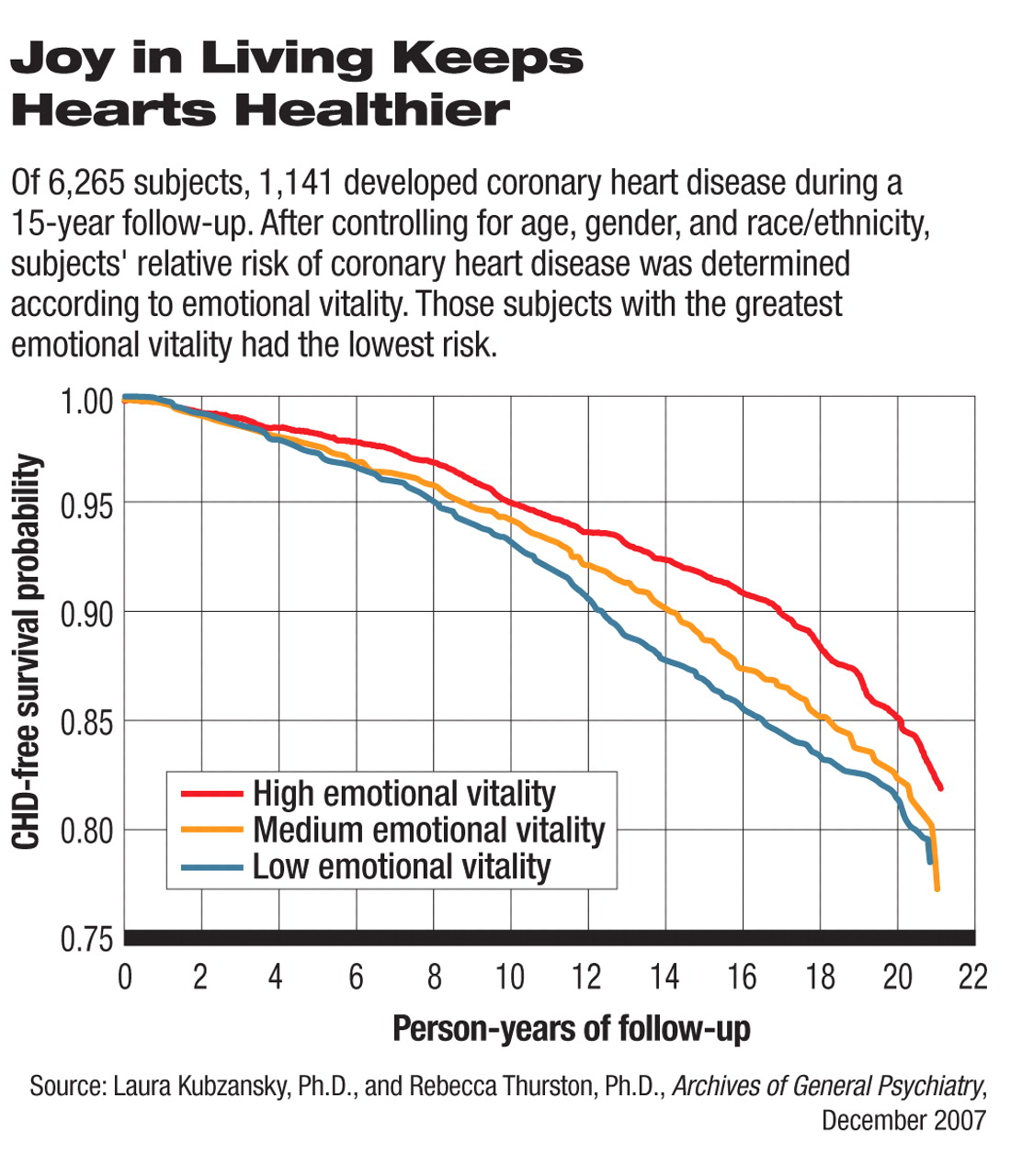

The subjects were then followed for 15 years to see whether they developed coronary heart disease. Measures of coronary heart disease were obtained from hospital records and death certificates. More than 1,000 subjects developed coronary heart disease during that time.

The researchers then looked to see whether subjects with higher emotional-vitality scores had significantly less coronary heart disease by the end of the 15-year period than subjects with less emotional vitality.

They found that after controlling for age, gender, and race/ethnicity, subjects with the highest levels of emotional vitality had a relative risk of 0.68 for coronary heart disease compared with subjects who had the lowest levels of emotional vitality.

Moreover, a highly significant dose-response relationship was evident: the greater the emotional vitality, the less the chance of having heart disease. And even when other possibly confounding factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, physical activity, a history of psychological problems, and current depressive symptoms were considered, the link between emotional vitality and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease remained statistically significant.

Finally, the researchers wanted to make sure that their finding couldn't be explained by some low-emotional-vitality subjects having undetected coronary heart disease at the start of the study. So they examined the association between emotional vitality and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease after excluding subjects who developed coronary heart disease within three years after the start of the study. The finding, however, remained unchanged.

“We were a little surprised that it remained so robust even after a number of other coronary heart disease risk factors were considered,” Kubzansky told Psychiatric News. So she and Thurston believe that emotional vitality can help protect people against coronary heart disease.

One way by which it might protect people, they speculated, is helping people respond effectively to challenges as well as provide reserve capacity for meeting those challenges. And a better meeting of such challenges would, presumably, put less stress on the cardiovascular system and thus help protect it.

The authors acknowledged, however, that a third factor such as genetics could account for both increased emotional vitality and decreased risk of coronary heart disease.