Spurred largely in response to the Virginia Tech shootings in April 2007, Virginia passed changes in its mental health law in March affecting standards for involuntary commitment. The new legislation also drew from the ongoing work of the state's Commission on Mental Health Law Reform, established six months before the campus tragedy.

A new criterion for involuntary admission to a “psychiatric inpatient facility for treatment” lies at the heart of the legislation. The old standard emphasizing “imminent danger” to self or others was replaced by “a substantial likelihood that, in the near future, he or she will cause serious physical harm to himself or herself or another person...” or “will suffer serious harm due to substantial deterioration of his or her capacity to protect himself or herself from such harm or to provide for his or her basic human needs.”

Representatives of the commission, the Virginia Tech Review Panel, legislative leaders, and Gov. Tim Kaine's (D) office agreed on a set of reforms for the legislative session that ended in March. Lawmakers also agreed to Kaine's proposal to allocate $42 million over two years for case management and emergency services for people with mental illness.

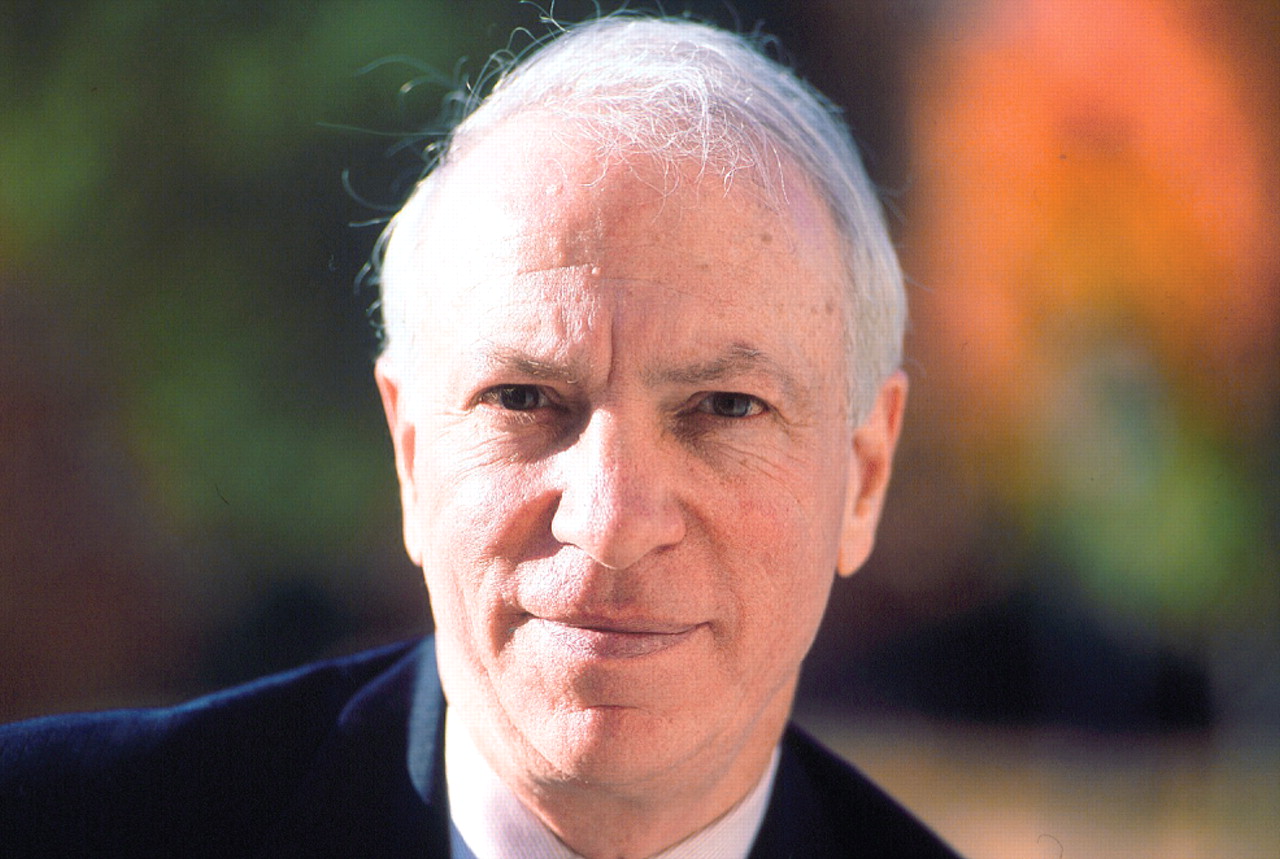

“These issues [addressed in the new law] were well understood by everyone,” commission chair Richard Bonnie, J.D., told Psychiatric News. “I think we had quite a successful session for what is really a first step in an ongoing effort.”

Bonnie is the Harrison Foundation Professor of medicine and law, a professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, and director of the Institute of Law, Psychiatry, and Public Policy at the University of Virginia School of Law. Bonnie is also a consultant to APA's Committee on Psychiatry and Law.

During the legislative process, the Psychiatric Society of Virginia (PSV) allied with other medical organizations and, in an effort led by the Medical Society of Virginia, pushed for expanded access to care for patients, higher standards of care, and patient privacy, said PSV President Steve Brasington, M.D., in an interview. On some counts, however, they came away disappointed.

“They've moved from a higher standard to a lower one,” said Brasington, a U.S Navy captain and director of mental health at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, va.

For one thing, said Brasington, a physician or even a doctoral-level psychologist will no longer be required to evaluate a person for commitment. An employee of the local community services board may do so.

Doctors were also removed from the commitment process to eliminate the appearance of financial conflict of interest should patients be committed to the doctor's own facility, Brasington believes. This possibility is remote, however, because facilities often lose money on the care of involuntary patients, and doctors are not reimbursed for the time spent at hearings, he said.

However, the status of who performs assessments reflects reality, Bonnie said.

“The problem is that in many parts of the state, there are no psychiatrists or psychologists available, so the law will allow a licensed counselor or social worker to be appointed as an independent examiner,” Bonnie told Psychiatric News. “Our goal was to promote consistency by trying to give more guidance to judges who make commitment decisions.”

Further, the statutory change requiring an independent examination was made almost 15 years ago, not by the commission, and it did not exclude the treating physician or others from the commitment process, explained Bonnie. The task force did consider how financial incentives have changed, but decided to retain the independent examination requirement.

“I do not feel that the psychiatrists' point of view was overlooked,” he said. “I believe that this is a case of variance bet ween percept ions (which we need to correct) and reality.”

The old commitment standard was open to broad interpretation, and so the new one might seem either looser or more restrictive, depending on one's point of view, said Bonnie. While dangerousness seemed the most salient issue to the public over the last year, in fact an earlier study found that a“ substantial inability to care for oneself” was the only reason for about half of all commitments in the state.

Virginia psychiatrists also were concerned about where persons committed under the new law would be placed.

'System Is Still Broken'

Brasington fears that more people would be committed under the new law, increasing the demand for inpatient psychiatric beds at a time when hospitals are cutting those beds because of poor reimbursement from insurers.

Without inpatient hospital beds allocated to mental health, some patients who are committed could tie up emergency department slots for several nights, controlled with multiple doses of medications, until they are stable enough to go home, said Brasington. That would defeat the purpose of commitment.

Bonnie disagreed. There is a shortage of beds in some parts of the state, he said, but not in most regions. Increasing the number of places for people who need beds would help, but beds in crisis-stabilization facilities may be an alternative to acute hospitalization for some individuals who are now being admitted to emergency rooms and hospitals for evaluations. Those services would be enhanced by a “major part” of the additional $42 million budgeted for mental health, so that inpatient rates would rise less than some fear, said Bonnie.

Confidentiality a Concern

Some mental health consumer groups also raised concerns about medical or psychiatric records becoming public once they are reviewed by a judge as part of the commitment process.

Under the old law, a patient had to affirmatively invoke confidentiality for his or her medical records. Seung Hui Cho, the gunman in the Virginia Tech killings, never did so, and his records became public after the shooting. Under the new law, the patient's medical and court records will be kept confidential at the court level, said Bonnie.

“Any disclosure can only happen with good cause and refer only to the court's order, not the person's health history,” he said. “The overall approach is that this is a therapeutic process, and only [sufficient] disclosure needed for an informed decision is permitted.”

More changes could come in the future, said Bonnie.

The Commission on Mental Health Law Reform, organized in 2006 by the chief justice of the Virginia Supreme Court, was originally scheduled to produce its final report late this year.

Despite that plan, greater public awareness following the Virginia Tech tragedy nevertheless led the commission to issue a preliminary report last December and to present specific reforms that could be taken up by the 2008 legislature.

Brasington said some psychiatrists felt excluded from the composition and purpose of the commission, which included only two physicians, both psychiatrists, who work as state administrators, but none from academia or private practice.

However, besides those two psychiatrists, at least five others were on the task forces that supported the commission, including three from the University of Virginia psychiatry department, said Bonnie.

“We just didn't realize that the psychiatrists with whom we were working on the commission and the commitment task force were not serving a liaison function with the psychiatric society,” he said. “I had no idea that the PSV felt excluded. We will take remedial action.”

Information about the Commission on Mental Health Law Reform is posted at<www.dmhmrsas.virginia.gov/OMH-MentalHealthCommission.htm>.▪