Five years after discharge, patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) treated with mentalization-based therapy during partial hospitalization followed by maintenance mentalizing group therapy showed clinical and statistical improvement on a range of measures compared with patients receiving treatment as usual.

Those measures included suicidality, diagnostic status, service use, use of medication, global function, and vocational status, according to a report in the March 17 edition of AJP in Advance.

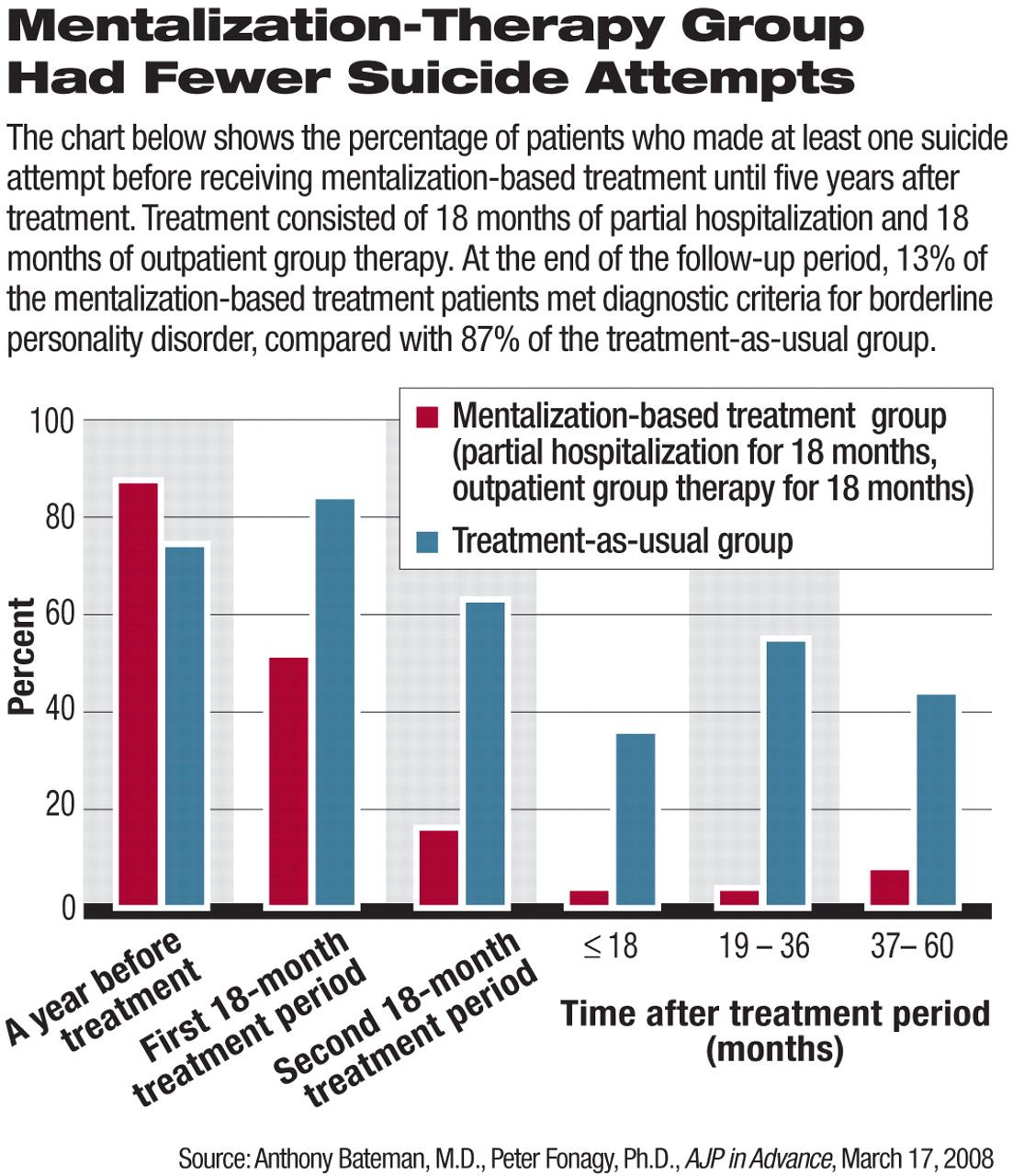

“More striking than how well the mentalization-based treatment group did was how badly the treatment-as-usual group” fared despite extensive treatment, wrote study authors Anthony Bateman, M.D., and Peter Fonagy, Ph.D.“ They look little better on many indicators than they did at 36 months after recruitment to the study. A few patients in the mentalization-based treatment group had made at least one suicide attempt during the postdischarge period, but this was almost 10 times more common in the treatment-as-usual group.

“The treatment-as-usual group also experienced more emergency room visits and greater use of polypharmacy,” Bateman and Fonagy added.

The study, “8-Year Follow-Up of Patients Treated for Borderline Personality Disorder: Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Treatment as Usual,” is the latest analysis of a randomized trial first reported in AJP in October 1999 and titled “Effectiveness of Partial Hospitalization in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial.”

Joel Paris, M.D., an expert on BPD, explained that mentalization therapy, developed by Bateman and Fonagy in the 1990s, is based on attachment theory and on observations that BPD patients have a failure of“ mentalization”—the ability to observe their own emotions and those of other people and to appreciate how their behavior may affect others.

“Mentalization-based therapy can be considered as an amalgam of psychodynamic and cognitive methods,” he told Psychiatric News.

For instance, a case report included in the study describes a 24-year-old woman who was referred from forensic services after her arrest for setting fire to her university dormitory.

She had a history of recent suicide attempts and regularly burned herself with cigarettes and a hot iron. In individual sessions, treatment initially focused on clarifying her own feelings and others' experience of her; later it progressed to helping her appreciate how her experiences of self-doubt and emotional turbulence led to a sense of fragmentation that was controlled only by experiences of intense physical pain, according to Bateman and Fonagy.

“The individual therapist identified these processes while focusing on the way she represented her own mental states and those of others with whom she interacted,” they wrote. “Gradually this was explored within the relationship with the therapist.”

They report the patient as stating, “It never occurred to me that what I did had an effect on anyone else.”

As explained in the 1999 AJP report, the original study was conducted at the Halliwick Psychotherapy Unit at St. Ann's Hospital in London. Halliwick offers partial hospitalization consisting of long-term psychoanalytically oriented treatment to 30 patients aged 16 to 65 who have borderline or severe personality disorder.

Forty-four patients were randomly assigned either to treatment by means of partial hospitalization or to standard outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization consisted of 18-month individual and group psychotherapy in a partial-hospital setting offered within a structured and integrated program provided by a supervised team.

Treatment for the partially hospitalized group consisted of once-weekly individual psychoanalytic psychotherapy; thrice-weekly group analytic psychotherapy (one hour each); and a weekly community meeting (one hour), all spread over five days. In addition, on a once-permonth basis, subjects had a meeting with the case administrator (one hour) and medication review by the resident psychiatrist.

Expressive group therapy using art and writing was included. Treatment as usual consisted of general psychiatric outpatient care with medication prescribed by the consultant psychiatrist, community support from mental health nurses, and periods of partial hospital and inpatient treatment as necessary but no specialist psychotherapy.

In the outcome analysis published last month, Bateman and Fonagy reported on 41 of the original patients. At six-month intervals after 18 months of mentalization-based treatment in partial hospitalization, they assessed treatment profiles—including emergency room visits, hospitalization, medication, suicidality, and self-harm. They also collected information twice yearly concerning vocational status, calculating the number of six-month periods in which the patient was employed or attended an educational program for more than three months.

Five years after discharge, the mentalization-based hospitalization group continued to show clinical and statistical superiority to treatment as usual on suicidality—23 percent in the mentalization group made at least one suicide attempt compared with 74 percent in the treatment-as-usual group over the the five-year postdischarge period.

Regarding diagnostic status, at the end of the follow-up period, 13 percent of the mentalization-based treatment patients met diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder compared with 87 percent of the treatment-as-usual group (see chart).

During the five years after discharge from treatment, the treatment-as-usual group received significantly more services—3.6 years of psychiatric outpatient treatment and 2.7 years of assertive community support, compared with two years and 5 months, respectively, for the mentalization-based treatment group.

Further, 46 percent of the mentalization-based treatment group had a global assessment of functioning score above 60 compared with 11 percent of the treatment-as-usual group.

The mentalization-based group also scored significantly better on use of medication after discharge from treatment and vocational status.

“This is the first study to follow patients treated with an evidence-based therapy for several years, and it shows that once patients get better, they tend to stay better,” Paris told Psychiatric News.“ So the take-home message is hopeful.”

He added that there has been no direct comparison of mentalization therapy to any other therapy, but said that all of the structured psychotherapies—including dialectical-based therapy, transference-based therapy, and schema-focused therapy—appear to be efficacious.

The poor outcome for patients in the treatment-as-usual group replicates a finding reported in a comparison of dialectical-based therapy and treatment as usual—suggesting to Paris that structure is critical for patients with BPD.

“All the studies show that a structured method is better,” he said. “The main problem with all the therapies subjected to randomized control trials is that they are lengthy and expensive, limiting access. Perhaps the cost is necessary, but it is also possible that streamlined versions of therapy can work.”