Has the “Rashomon” effect come to the doctor's office?

Parents in a recent study said they did not receive counseling for their children's mental health problems in 75 percent of the visits with primary care providers in which the primary care providers said they had delivered it.

Psychiatrists and pediatricians have been experimenting with ways to improve mental health diagnosis and care at the primary care level, either by making referral simpler or quicker or by deepening the knowledge of primary care providers.

The new study suggests that process may also involve a complex set of factors attributable to both providers and parents, wrote Jonathan Brown, Ph.D., M.H.S., of Mathematica Policy Research in Washington, D.C., and Lawrence Wissow, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of health, behavior, and society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. Their report appeared in the December 2008 Pediatrics.

Their analysis was based on data drawn from a study of how nonspecific“ common factors”—helping providers engage and involve children and parents, addressing hopelessness and anger, the therapeutic alliance, decreasing barriers to care, increasing patient motivation—often result in better outcomes than more specific treatments, said Wissow in an interview.

In this study, Brown and Wissow documented the results of 749 visits to 54 pediatric primary care providers at 16 practices in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and a rural area in upstate New York. Forty-four of the providers were physicians, nine were nurse practitioners, and one was a physician assistant. Patients were aged 5 to 16, and 27 percent had high levels of mental health symptoms.

Immediately after the patient visit, the providers and parents answered one yes-or-no question each about mental health counseling in the encounter. Parents were asked whether the provider counseled them about the child's mood, behavior, ability to get along with others, parental stresses, or family problems. Providers were asked if they had given counseling for a psychosocial problem requiring clinical attention.

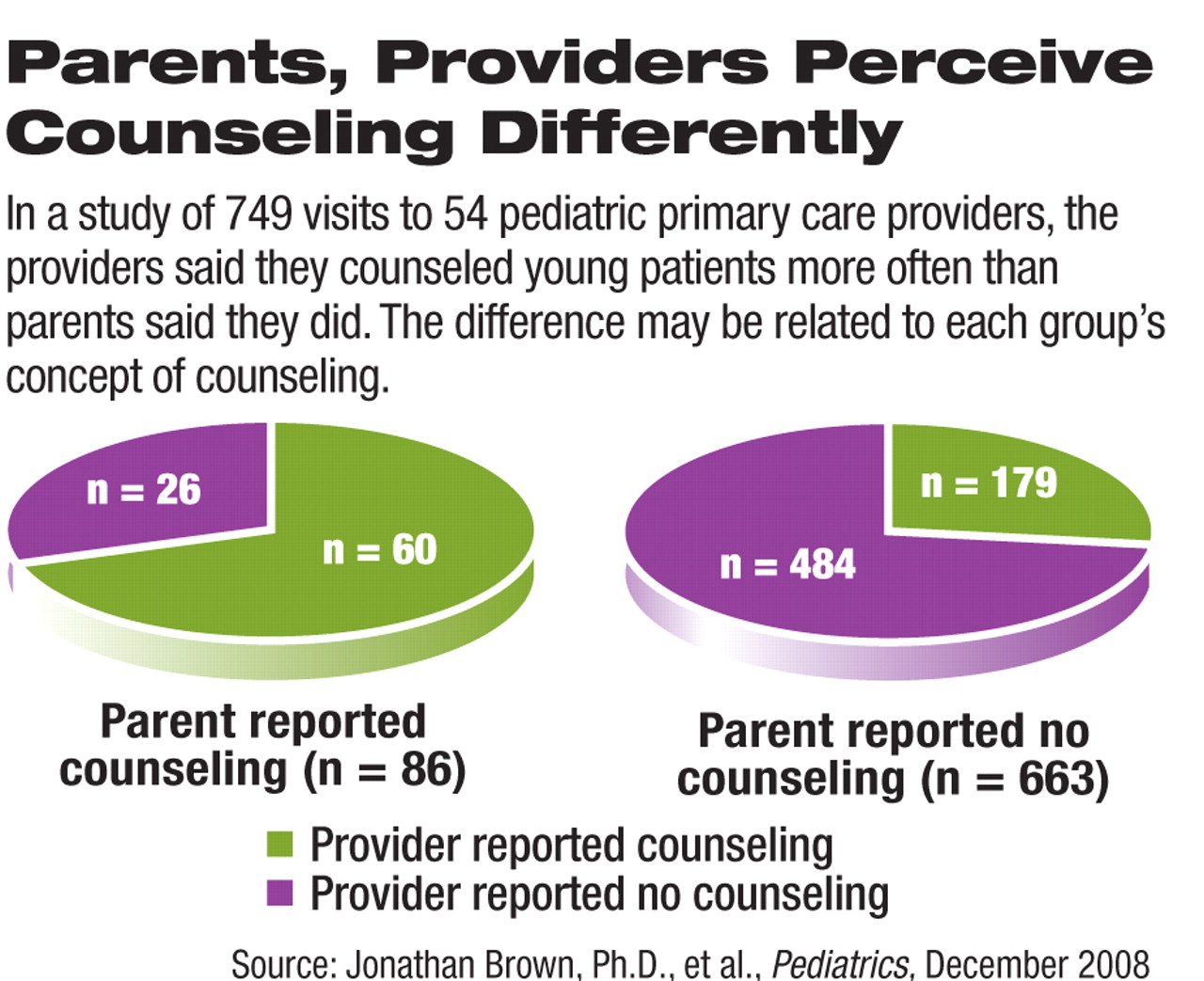

The providers said they gave mental health counseling to parents of their young patients at 239 visits (32 percent), yet parents reported such counseling at just 179 visits (11 percent). (Curiously, parents did report counseling at 26 of the 510 visits in which the providers said they had not provided it. See chart.)

The odds of parents' reporting no counseling rose if they also said the visit was for mental health reasons, there was any discussion of mental health, or if a provider was more burdened by delivering mental health treatment.

“Burden is a combination of things, but mainly the anxiety of having to deal with mental health issues,” he said. “Providers worry that if they bring up these issues, the patient will emote, the doctor won't know what to do and will fall further behind in the day's work, and nobody will be happy.”

The two parties' definition of counseling seemed to be the same, but parents' expectations may have something to do with the results.

“When you say 'mental health care,' people still think of medications or psychotherapy, not a reframing of the problems they came in with,” said Wissow. So even if a family walks out with a sense that their concerns have been heard, that their problems are common enough with children that age, or that it may help to talk to the school counselor, they may think that the provider has not specifically helped them with a mental health issue.

“Providers may not be good enough at framing what they are doing as mental health care,” said Wissow.

“[They] may require [more] skills to communicate efficiently and effectively with families about mental health when faced with competing demands and fewer resources,” wrote Brown and Wissow. “Such skills should help [primary care providers] overcome language or cultural barriers, clarify what the parent and youth hope to gain from the visit, and investigate whether their expectations have been met.”

The providers may be doing better over the longer term than they are right after the visit. Brown and Wissow are still analyzing follow-up data, but Wissow said that both clinical outcomes and parental views seem improved six months after the visit recorded in the study.