U.S. military health officials are using an ambiguous and unvalidated method of identifying mild traumatic brain injuries among troops returning from service in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to three Army medical researchers.

The Department of Defense now uses a brief checklist after the troops return from the war zones to screen for medical consequences of deployment. Only one question on the Post Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) form asks about possible traumatic brain injury (TBI).

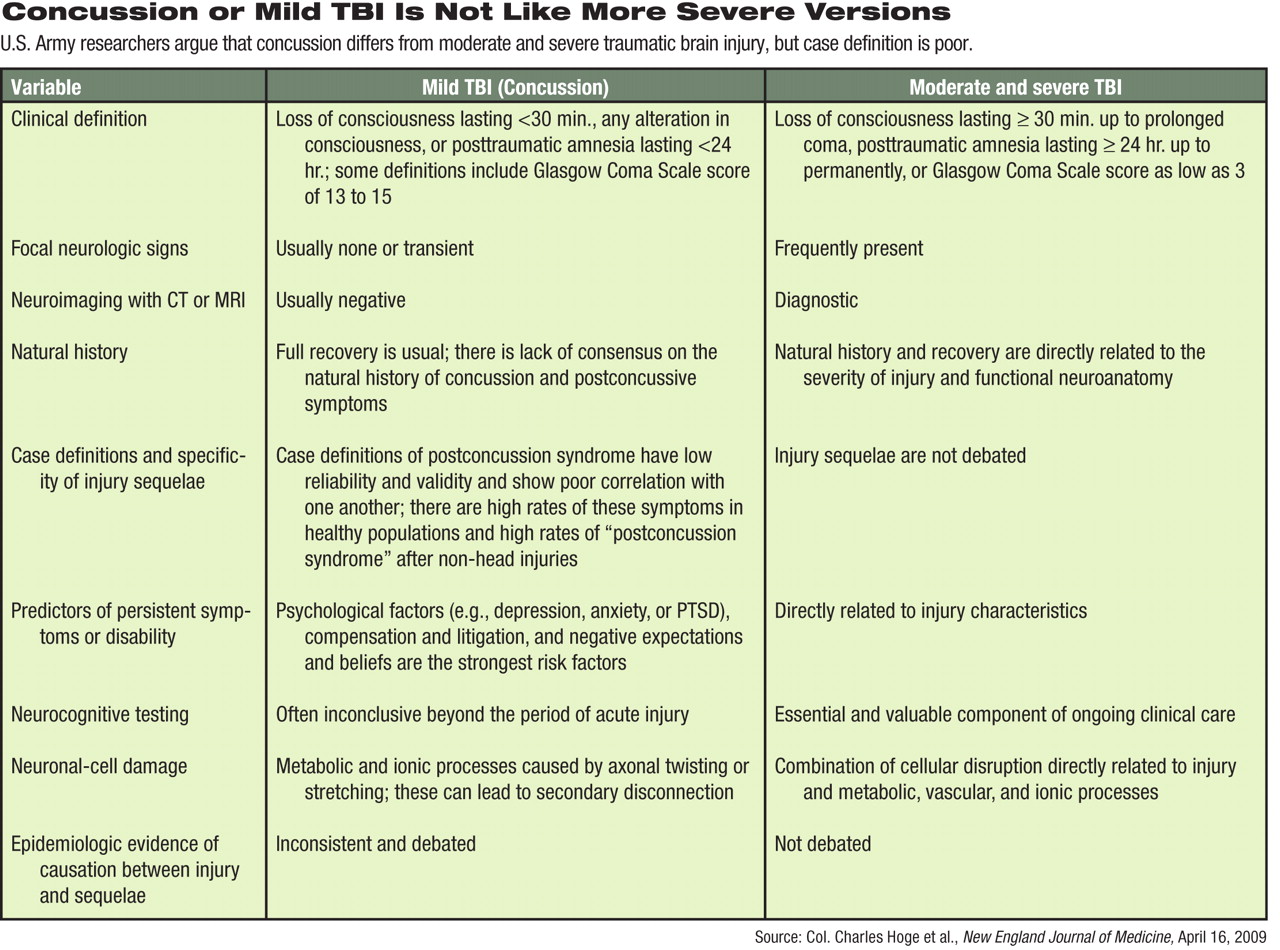

The resulting information does not amount to a case definition because it lacks three essential criteria for use months after injury: symptoms, time course, and impairment, wrote Col. Charles Hoge, Col. Carl Castro, and Herb Goldberg in the April 16 New England Journal of Medicine. Hoge is director of the Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and Goldberg is a communications specialist there. Castro is a psychologist and director of the Military Operational Medicine Research Program at Fort Detrick, Md.

Previously, other military health officials have stated that as many as 360,000 (20 percent) returning troops have experienced at least transitory effects of blasts from improvised roadside bombs or other explosives, although half of those cases resolve by the time of return to the United States (Psychiatric News, April 3). The remaining cases may require further treatment in primary or specialty care, either in the Department of Defense or the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical systems.

As they return home, service members are asked to recall if they were exposed to a blast and if they were also “dazed or confused” at the time, were unconscious for less than 30 minutes, or had posttraumatic amnesia due to concussion or mild TBI.

“Positive responses to this single, unvalidated question have accounted for two-thirds of all reported cases of concussion/mild TBI,” they wrote. The current system may be inflating the number of cases.

“The issue is one of 'caseness,' how to define a person with mild TBI or concussion,” explained Castro, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “For any symptom-based disorder or injury, a case is based on five factors, each of which has to be independently validated: an event, the reaction to the event, symptoms, impairment, and a time course.”

The 360,000 figure is based on only two of those elements, the event and the reaction, neither of which has been validated, said Castro. “So they're saying, 'The soldier has been injured, but he has no injuries.'”

Furthermore, high rates of these symptoms occur in healthy populations, and“ postconcussion syndrome” appears after injuries to areas other than the head. Validation of current case definition is poor, he said.

Terminology is fluid, but usually TBI refers to the injury itself, and postconcussive syndrome applies to what follows the injury, said James Couch, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of neurology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Neurology. Much of the controversy comes from the fact that many symptoms associated with concussion or mild TBI—such as headache, sleep disturbance, irritability, dizziness, balance problems, fatigue, or poor concentration—are not specific to head injury, he said.

“[C]linicians' attribution of such nonspecific symptoms to concussion/mild TBI is subjective,” but the present screening process assumes that they are causally related, wrote Hoge and colleagues.

They are also concerned that the present approach encourages negative expectations about recovery, complicated by possible secondary gain, and inappropriate treatment.

“This is an excellent review of the clinically sensitive and policy-relevant consequences of poorly defined diagnostic criteria for mild traumatic brain injury,” said Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of APA's Office of Research and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education. “There has been reluctance in the Department of Defense to use the diagnosis of postconcussive syndrome simply because of the stigma attached to this being a mental disorder—however transient—rather than a neurological disorder.”

Failure to address the consequences of the current concepts of mild TBI could easily lead to expectations of permanent brain damage for those so diagnosed, as happened with soldiers returning from World War I diagnosed with shell shock, said Regier.

Hoge, Goldberg, and Castro have received a mixed response from higher ups to their recommendations.

“Some are supportive, some want more debate and discussion,” said Castro. “We want to keep the discussion going until we get the right mixture of policies and procedures in place.”

In response to the perspective in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Pentagon unit charged with researching TBI acknowledged that there was no clear standard of care for it in the early years of the two current wars, but it has been collecting data to improve screening and clinical practice, said Michael Kilpatrick, M.D., director of strategic communications for the Military Health Service.

“Today DoD [Department of Defense] continues to analyze the data that have been collected to make the best scientific changes to processes to optimally identify, document, and treat mild TBI/concussion,” said Kilpatrick in a prepared statement. “The Hoge paper is the expression of an opinion supporting this scientific process.”

How DoD and the VA ultimately define mild TBI will have implications not just for diagnosis but for treatment, compensation, and long-term care for returned veterans.

“The research of Hoge and colleagues has guided discussions of the DSM-V trauma-related diagnostic criteria and has helped APA improve the Defense Department's proposals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the CDC's [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's] National Center for Health Statistics to revise the ICD-9-CM classification of cognitive and behavioral consequences of concussion and TBI,” said Regier.

Castro sees the paper by him and his colleagues as just one element of a continuing debate aimed at getting the best possible solution for TBI issues in veterans.

“Charles Hoge and I want every service member to return home and live a happy and productive life,” he said. “If any program, policy, or procedure for which the scientific evidence is not appropriate hinders that, then we need to speak out.”