Antidepressant medications have gained wider acceptance and popularity, accompanied by declining use of psychotherapy, in the treatment of depression in the United States from 1996 to 2005, a study published in the August Archives of General Psychiatry demonstrates.

The authors, Mark Olfson, M.D., and Steven Marcus, Ph.D., compared the rates of antidepressant use in 1996 and 2005 using data collected in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)–household component. The ongoing survey was first conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 1996.

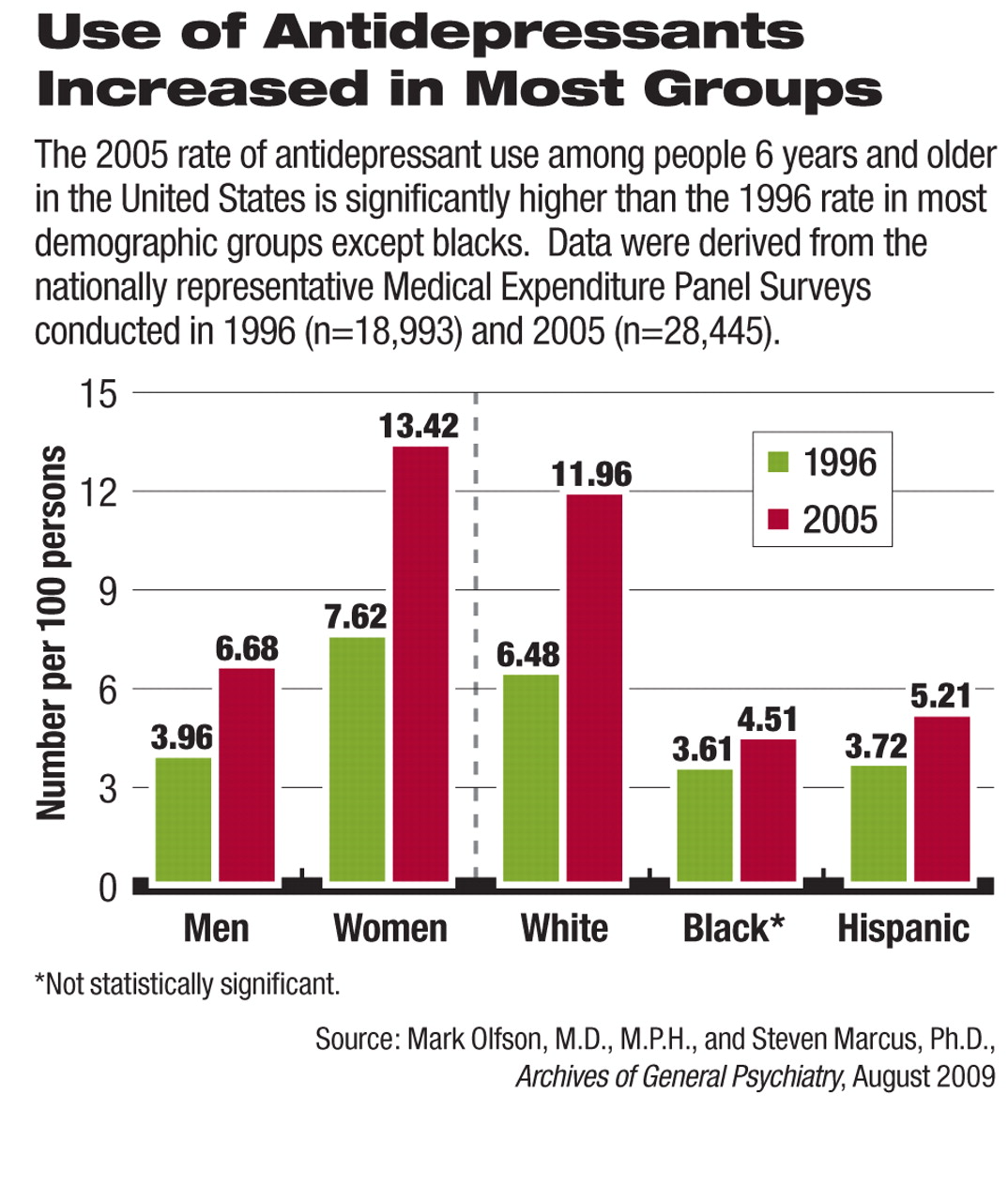

In 2005 the annual rate of antidepressant use was estimated at 10.12 percent, nearly doubling from the 5.84 percent documented in 1996. Compared with 1996, the rates of antidepressant use in 2005 increased with statistical significance regardless of sex, age group, marital status, educational level, family income, health insurance type, and employment status. The rate of antidepressant use increased significantly among white and Hispanic, but not black, respondents.

Olfson is a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University Medical School and New York State Psychiatric Institute. Marcus is a research associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy and Practice. The study was supported by grants from the AHRQ and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

During the year of MEPS, trained interviewers visited and interviewed a large sample of households throughout the United States and asked respondents to record their and their family members' health care visits, reasons for the visits, and treatments including medications throughout the year. Their diagnoses and health care visits were validated by respondents' medical records. Olfson and Marcus limited their analyses to people 6 years and older and included nearly 19,000 people from the 1996 survey and over 28,000 from the 2005 survey.

Among people who were treated with antidepressants, 5.45 percent also received antipsychotics in 1996, compared with 8.86 percent who also received antipsychotics in 2005, while the percentage of patients who also received psychotherapy declined significantly from 31.50 percent to 19.87 percent. Meanwhile, the rate of inpatient mental health service decreased significantly from 3.93 percent to 2.08 percent.

Fewer than 1 in 4 antidepressant users was being treated by a psychiatrist in 2005. This information was not collected in the 1996 survey, thus making a comparison impossible, Olfson told Psychiatric News. The rates of treatment by psychologists and social workers were about 9 percent and 4 percent, respectively, in 2005.

The authors suggested a number of explanations for the increase in antidepressant use, including more new drugs being approved, less stigma for mental illness, growing acceptance of psychopharmacological treatment by the public and general medical sectors, and a near fourfold increase in direct-to-consumer advertising to promote antidepressant drugs. The indications of antidepressants have expanded in the decade, which may also explain the growth of their popularity. The percentage of all antidepressant users who were being treated for depression barely changed from 1996 to 2005—from 26 percent to 27 percent. Other conditions for which they were treated included back pain, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disorder.

The study authors offered several possible explanations for the increased antidepressant use. Two national surveys showed that the prevalence of major depression in adults rose from 3.3 percent in 1991-1992 to 7.1 percent in 2001-2002. “It is difficult to know whether depression became more common . . . or people just became more willing to disclose that they were depressed. Whatever the reason, a larger percentage of the population endorsed the symptoms of major depression in the later time period,” said Olfson.

“The overall increase in the use of antidepressants since the mid-1990s is consistent with previous reports and with general clinical experience,” David Fassler, M.D., commented to Psychiatric News. Fassler is a child psychiatrist and APA secretary-treasurer.“ Physicians and the general public are more aware of the signs and symptoms of depression, and treatment with medication is more widely accepted.” He found the decline in psychotherapy use unfortunate, as“ research clearly demonstrates that psychotherapy is a valuable and important component of treatment for many people with depression.”

Despite the increased rate of antidepressants, these data do not measure the quality of diagnosis and treatment for patients with depression and other mental illnesses, the authors acknowledged. They pointed out one disconcerting dataset: 52 percent (1996) to 65 percent (2005) of MEPS respondents with bipolar disorder were prescribed antidepressants. The effectiveness and risk of antidepressants in bipolar treatment are still controversial.

“In the long run, the real issue isn't simply how many people are taking antidepressants,” said Fassler, but rather “whether or not the right people are getting the most effective and appropriate intervention possible.”

Recent studies have suggested that the national trend of rising antidepressant prescriptions since the 1990s may have flattened or reversed since late 2004 when the Food and Drug Administration issued a series of public warnings about increased risk of suicidality in young patients associated with antidepressants (Psychiatric News, July 17). A boxed warning was required for all antidepressant drug labels in February 2005. This study, a cross-sectional comparison between 1996 and 2005, does not directly address this more recent trend.

An abstract of “National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment” is posted at<archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/66/8/848>.▪