A combination nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than other smoking-cessation treatments for maintaining abstinence, report researchers in the November Archives of General Psychiatry.

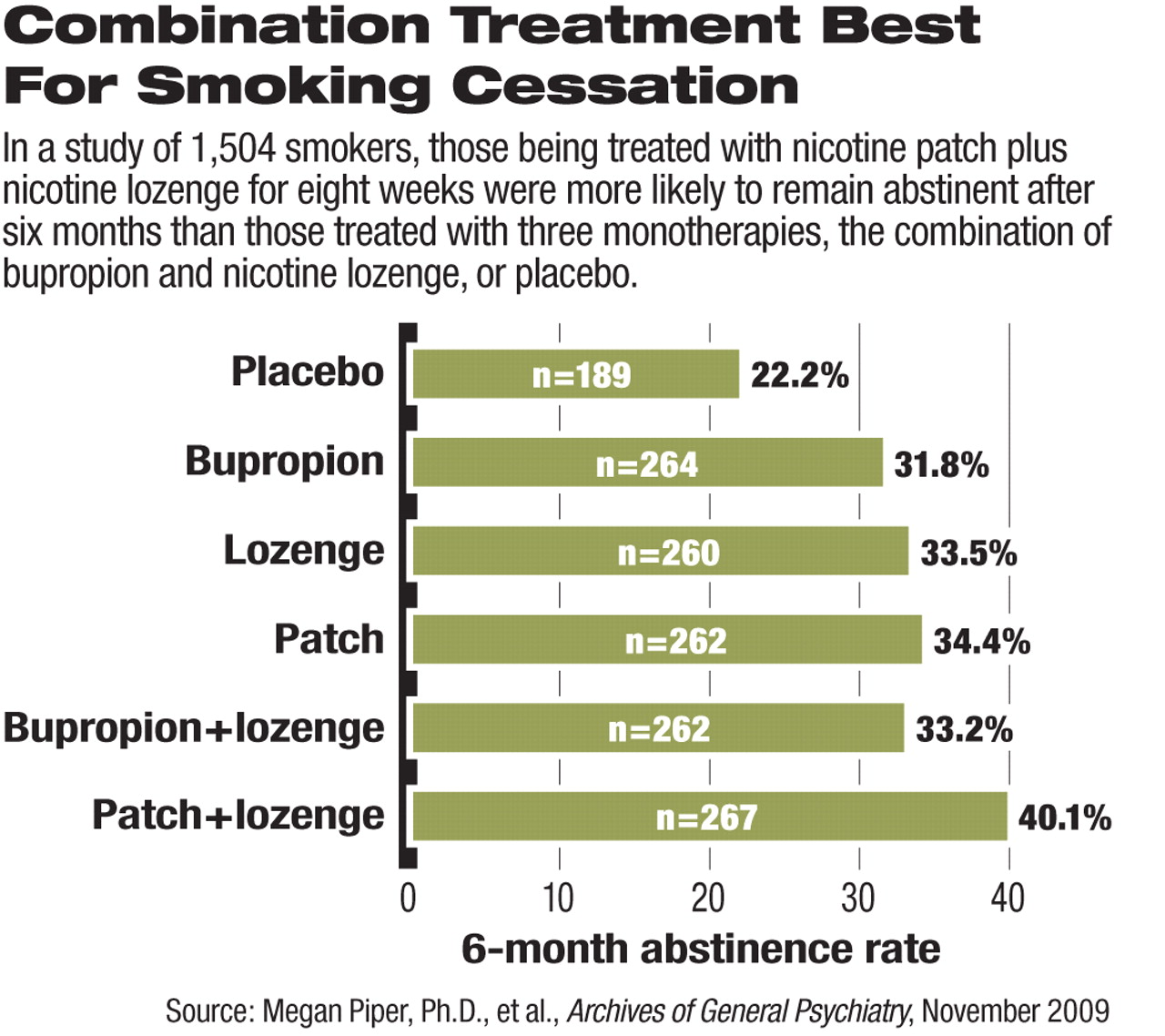

In a three-year study, 1,504 participants who were smoking at least 10 cigarettes a day and motivated to quit were randomly assigned to one of six smoking-cessation treatments: (1) nicotine lozenge, (2) nicotine patch, (3) bupropion sustained-release tablet 150 mg twice daily, (4) nicotine patch and nicotine lozenge, (5) bupropion and nicotine lozenge, or (6) placebo.

Participants received study treatments for eight weeks after their quit date, except for those taking bupropion, who began treatment one week before their quit date. Six individual counseling sessions were also provided for each participant before and after the quit date. After eight weeks of treatment ended, participants had two follow-up assessments—at weeks 12 and 26.

The rate of seven-day abstinence (no smoking in the prior week) was higher for participants who were on any of the five active treatments than it was for those on placebo. This difference was statistically significant at one week after quit date, at the end of the eight-week treatment, and at six-month follow-up.

After statistical analyses, the authors concluded that “the nicotine patch plus lozenge combination emerged as the treatment with the strongest support,” though the other treatments were more effective than placebo in maintaining abstinence from smoking.

Even the placebo group achieved a 22 percent abstinence rate at six months. In other groups, the rate of abstinence at six months ranged from 32 percent (for those on bupropion) to 40 percent (for the patch and lozenge combination). These rates were higher than those found in previous studies of smoking cessations, perhaps because of the inclusion of counseling sessions for all participants during the study, the authors suggested. A previous randomized, open-label study of nicotine patch and nasal spray, published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research (issue 2, 2003), found that 20 percent of study participants were abstinent from smoking after six weeks and 8 percent were abstinent at six months.

“Combining counseling and medications provides the best outcome,” Megan Piper, Ph.D., the lead author of the study, told Psychiatric News. She is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. If clinicians are unable or unwilling to offer smoking-cessation counseling, they can refer patients to the nationwide hotline at (800) QUIT-NOW, she added. “Everyone has access to this free service.”

In order to facilitate the head-to-head comparisons under a double-blind condition, participants in Piper's study who were assigned to the placebo group were randomized to receive inactive patch, lozenge, tablet, or two combinations of those.

Abstinence was assessed primarily by self report at each follow-up visit. Participants were asked whether they had smoked in the past seven days and whether they had smoked at all since the start of the study. A carbon monoxide breath test was used to confirm self-reported abstinence.

The study excluded volunteers who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychosis, or bipolar disorder. Piper explained that the researchers were concerned about the safety of using bupropion in patients with these illnesses, especially bipolar disorder. In addition, the study did not include varenicline as a comparator, because the drug was not available when the study began.

The adverse events reported during the study were consistent with those found in previous smoking-cessation studies. Skin irritation was the most common complaint for patients using the patch, sleep disturbance/abnormal dreams for bupropion, and nausea for the lozenge. One patient was hospitalized for a seizure, which was deemed possibly related to bupropion.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.