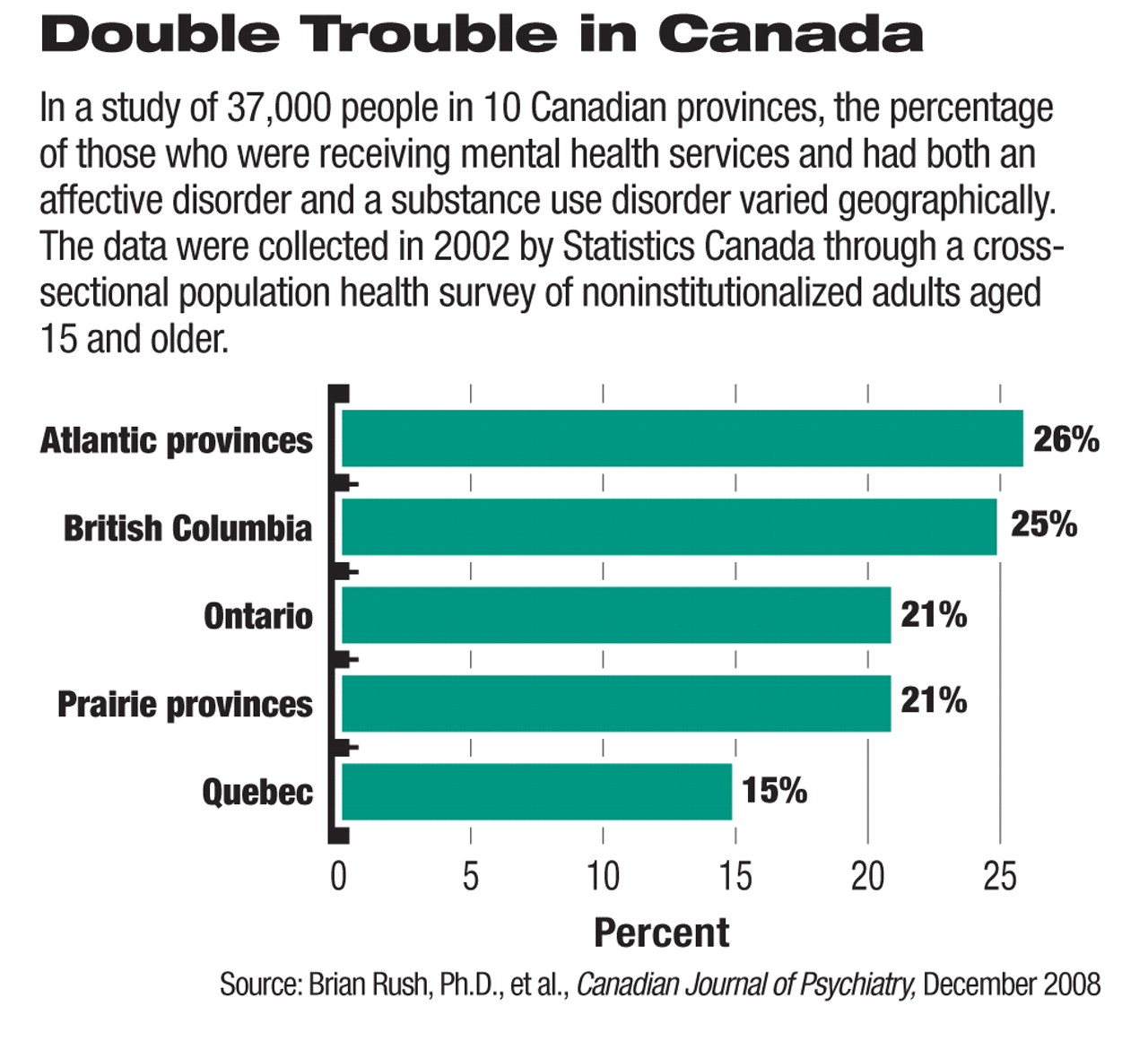

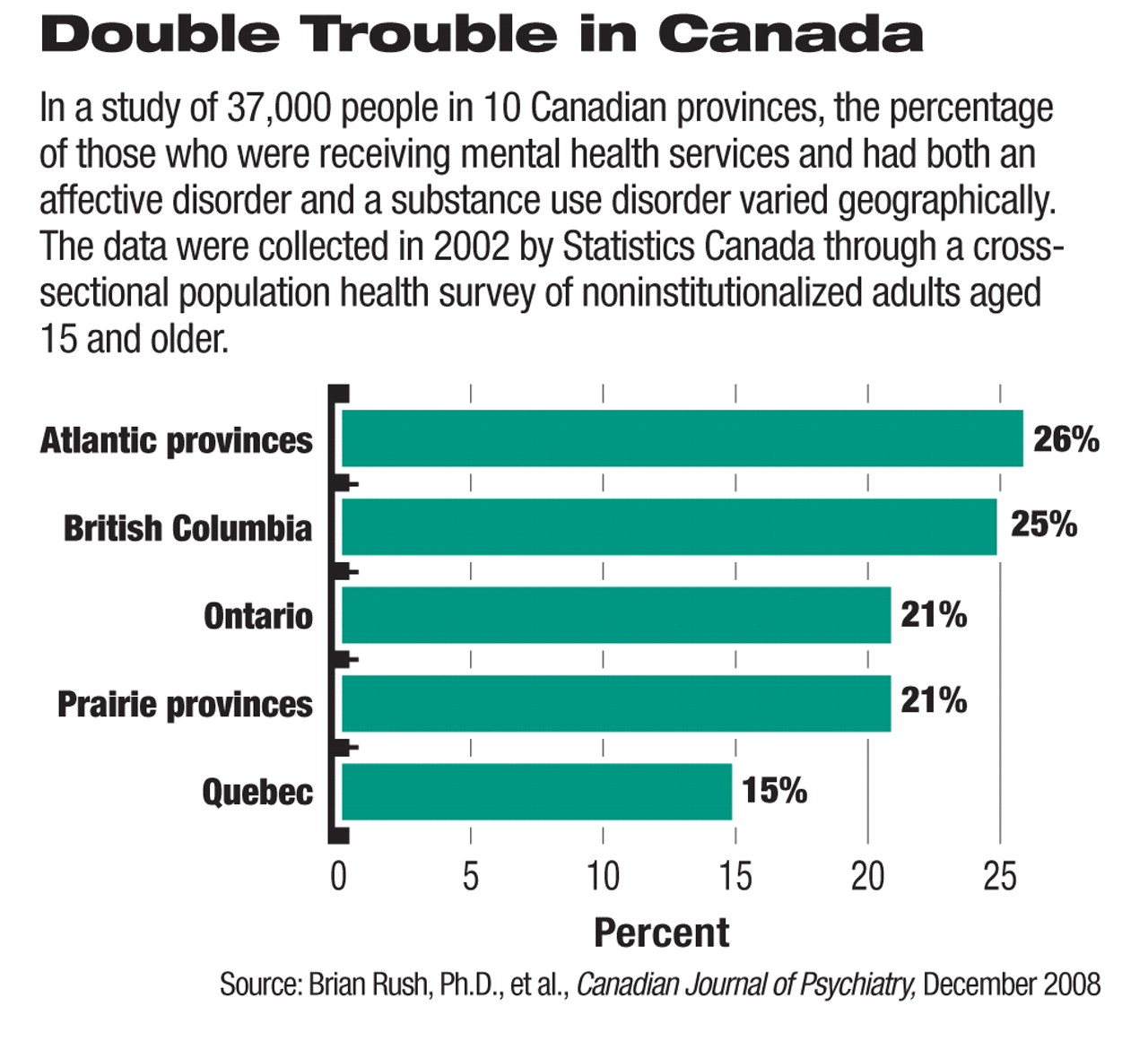

How many Canadians have both an affective disorder and a substance use disorder? Who are they? Where do they live? For what appears to be the first time, a study has tackled these questions, according to researchers.

The study, which included a nationally representative population sample of some 37,000 people, was headed by Brian Rush, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Results appeared in the December 2008 Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Overall, 2 percent of Canadians had both an affective disorder and a substance use disorder in the year prior to the study. (An affective disorder could be DSM-IV depressive episodes, manic episodes, panic disorder, social phobia, or agoraphobia. A substance use disorder could be alcohol abuse short of dependence, alcohol dependence, illicit drug use short of dependence, or illicit drug dependence.) This finding surprised him and his colleagues, Rush told Psychiatric News. They thought that the percentage would be higher, but he added that he and his colleagues “were reassured [that this finding was accurate] by its comparability with the most recent and best-conducted American study.”

Of course, this finding does not minimize the burden that those Canadians who have both an affective disorder and a substance use disorder experience, he stressed. Moreover, a large number of Canadians who seek mental health services have such comorbidity, he noted.

Still other valuable findings emerged from the study. Among them:

•

The prevalence of substance use disorders among Canadians with affective disorders decreased with age.

•

The co-occurrence of an affective disorder and a substance use disorder was more common in certain subgroups of Canadians than in others. For instance, one-third of Canadian women with an illicit drug use disorder were found to have an affective disorder as well. And compared with women with an affective disorder, men with an affective disorder were twice as likely to have an alcohol use disorder and three times more likely to have an illicit drug use disorder.

•

Canadians in certain regions were more at risk of having both an affective disorder and a substance use disorder than were Canadians in other regions. For example, a mood disorder accompanied by an alcohol use disorder was most prevalent in Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island) and least prevalent in Quebec. A mood disorder accompanied by an illicit drug use disorder was most common in British Columbia and least common in Quebec. Of Canadians who had both an affective disorder and a substance use disorder, most were found in Atlantic Canada and British Columbia, a fair number in Ontario and the Prairie provinces, and the fewest in Quebec. These regional differences “were unexpected,” Rush said.

These results, among others from the study, raised some crucial questions, Rush and his colleagues pointed out in their report. For instance, why were Québécois less prone to a dual affective-substance use disorder than Canadians in other provinces? Rush and his group don't know. However, there are a number of possible explanations, they speculated:“ lifestyle, health care, social and legal policies, income inequality, or migration patterns.” And if they can find the answers, the answers might offer some valuable insights into factors that help protect people against a comorbid affective disorder and substance use disorder.

The results likewise have implications for psychiatrists, Rush told Psychiatric News. “[They] should be vigilant for substance use disorders among those accessing their services. There also needs to be thoughtful and well-integrated mental health and addiction services to assess and respond appropriately to the co-occurring disorders. Historically people with [such comorbidity] ... have been confronted with seeking help from two separate and often ideologically conflicting service-delivery systems. Much work is being done in Canada, the United States, and other countries to rectify this situation to improve client experiences and outcomes. But much [still] remains to be done.... [Canada's] new Mental Health Commission should serve to direct needed attention to the issue of co-occurring disorders.”

The research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care.