Psychoanalysis may be able to help some children with autism or an autism spectrum disorder make dramatic progress toward normalcy.

So reported psychoanalyst Susan Sherkow, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, at the January meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association in New York City.

Moreover, during the meeting, she provided details about one patient to make her case. Later, during a phone interview, she said that she has also used psychoanalysis with five more children who were “flat-out autistic” or “on the spectrum,” and that the outcomes in these cases too were quite positive. The six children ranged in age from 2 to 9 when they started analysis, she said.

Autistic children tend to have difficulty communicating verbally, or even if they can talk, it is often difficult to understand them, Sherkow explained to Psychiatric News. Nor is it always possible to know whether what they are saying is connected to what they are thinking or feeling. So a major goal of her analysis with each of the six children (five boys and one girl), she said, was to “pay very close attention to the child's behavior” so that the behavior would give her clues to thoughts and emotions. And once she had decided on how to interpret the child's behavior, she would verbalize it in her or his presence. For example, if the child appeared to be upset, she would say, “You're upset.” Or if he or she appeared to be angry, she would say, “You must be angry.” And if the child gave her a furtive glance after she made such a comment, she would conclude that her interpretation of the behavior was probably correct. So by using such techniques over a period of weeks, she came to understand quite well what the child was thinking and feeling when he or she engaged in various behaviors, she said.

Further, her verbally expressing her interpretations of the child's behaviors in his or her presence served another purpose, she pointed out. The child came to realize that thoughts and feelings were being understood. She was forging a relationship with the child.

Another goal of the analysis was to help the child relinquish stereotypic behaviors for imaginative play, Sherkow reported. “These kids are typically lacking in imaginative play,” she said. “Imaginative play comes from having used language and from having identified emotions with language.”

Also, the mother of each of the six children was present during her child's analytic sessions, Sherkow noted. There were several reasons why the mother was included, Sherkow said. One was to help the mother recognize what her child was thinking and feeling. Another was to help her and her child communicate verbally with one another. Yet a third goal was to demonstrate to her that her child could be helped.

The six children whom Sherkow analyzed were in analysis anywhere from two to four years, she said.

“All six significantly improved in outcome,” Sherkow reported,“ but I will clarify that since 'outcome' is a very broad word.... By the end of the first year of analysis they had developed empathy.... They can socialize with other children and communicate their needs. They can say 'I'm angry,' 'I'm sad,' 'I'm hungry,' or 'I'm tired.' They look like a child without a diagnosis. I would say that they all arrived at that.... Some have even gone on to mainstream schools....”

How much of these children's impressive outcomes were actually due to analysis?

Sherkow is the first to admit that she is not sure, especially since the children were also receiving speech therapy and occupational therapy and, in some cases, physical therapy. Further, she and the other therapists worked closely together in each case “to make sure that everybody was on the same page.” Nonetheless, she has little doubt that the children's remarkable results were due at least in part to analysis. For example, her patient who had started analysis at age 9 had already had speech therapy, and it had done nothing to help him with his grave speech difficulties. But now, after analysis, “he is understandable,” she reported. “You can actually have conversations with him.”

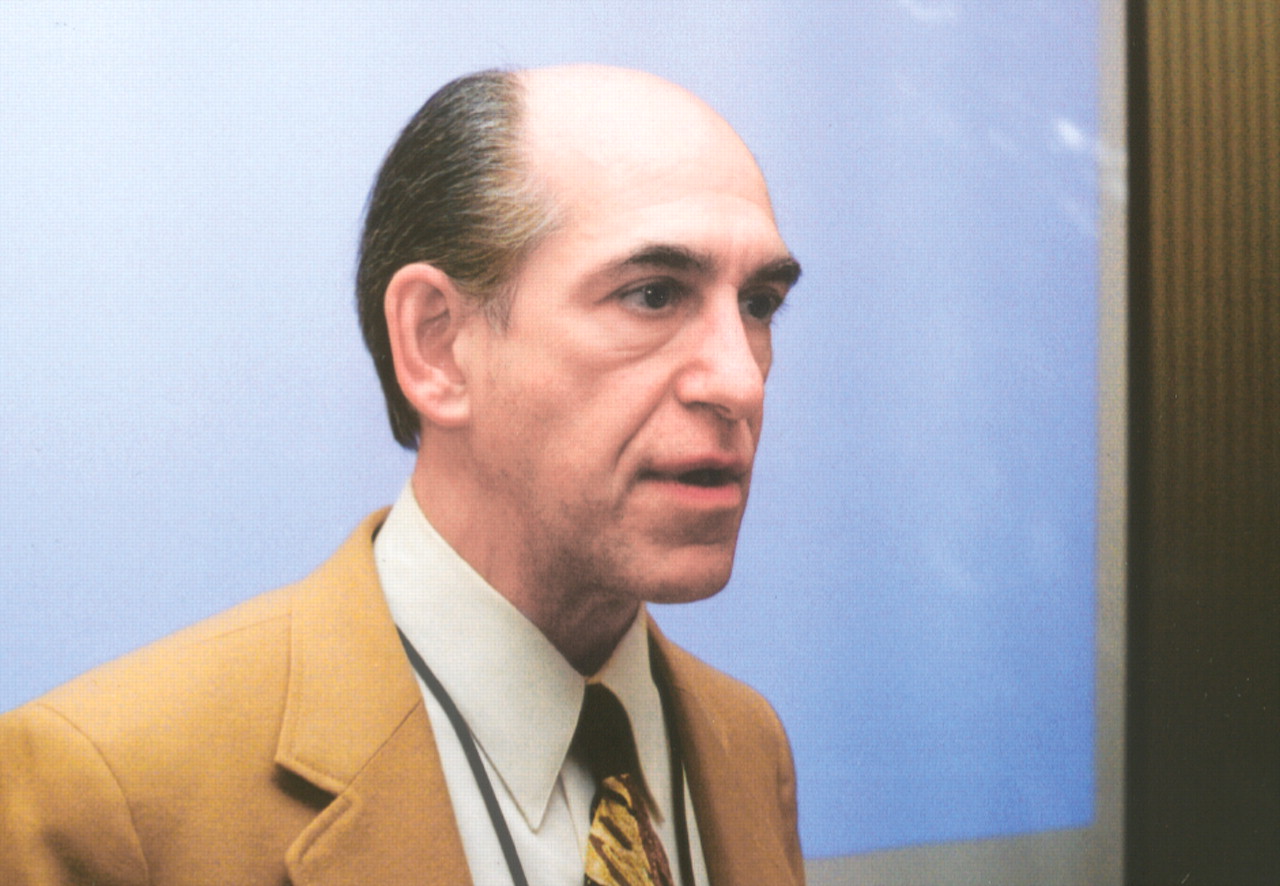

Sherkow's greatest achievement may have been in making the children empathetic, Emanuel DiCicco-Bloom, M.D., a professor of neuroscience at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and an autism scientist, declared at the APsaA meeting. “It is heartwarming, something we don't hear about at our autism meetings,” he added.

But perhaps the more sweeping implication of these outcomes, DiCicco-Bloom pointed out, is that they challenge the traditional belief that children with a diagnosis of autism or of an autism spectrum disorder cannot get better.“ We are learning that the brain has an incredible amount of plasticity,” he declared. “There is far more plasticity than many of us would have imagined even 10 years ago.”

Sherkow agreed: “One of the main things we are up against in our work is that there has been a lot of press over the years that you can't lose the diagnosis of autism.... Now we are beginning to see that that is just not true.”

Other American analysts are also using analysis to help autistic children, Sherkow noted. So are some European analysts, she added. So does she recommend that children with autism or an autism spectrum disorder receive psychoanalysis? “Absolutely!” she replied. And where might American parents find an analyst to help an autistic child? “They should go to a psychoanalytically trained child psychiatrist or child psychologist who knows how to do this or who would learn how to do it because it is based on how we do child analysis anyway.” ▪