More of the U.S. population would be eligible for Medicaid coverage under health care overhaul legislation being considered by Congress. Widening the Medicaid safety net could have major consequences for people with mental illness who have trouble accessing care but also could impact states struggling to meet current Medicaid commitments.

Health care reform legislation could expand the program from certain categories of people with incomes of less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), who are now covered, to all Americans with incomes up to 150 percent of the FPL.

The House-passed health care reform bill (HR 3962) would expand Medicaid eligibility by 2013 to all individuals with incomes of up to 150 of the FPL ($16,200 for an individual in 2009). The cost of care for these new Medicaid enrollees would be borne by federal taxpayers, not shared equally with the states as is now the case with Medicaid.

Senate negotiations over its version of health care reform have also included a proposal to raise Medicaid eligibility to the same level as the House bill, but as currently written in the leading Senate bill (HR 3590), people earning up to only 133 percent of the FPL would gain Medicaid eligibility.

The House bill would reduce the number of uninsured individuals by 37 million by 2019, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Among those, 11 million, or about 30 percent, would move into Medicaid by 2019 and bring total Medicaid enrollment to 85 million people, or about 25 percent of the U.S. population. The Senate proposal would add 15 million beneficiaries to Medicaid.

Critics, including Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.), a physician, disparaged the proposed expansion.

“That's banishing people to a substandard system, compared to what's generally available in this country,” Coburn said in a Senate floor speech.

Supporters of expanded Medicaid access, including many mental health care advocates, highlight the expansive coverage—compared with many private insurance plans—of treatment for psychiatric illnesses provided by Medicaid. It is already the largest single payer for mental health care in the United States, funding about 25 percent of all such care.

Laurel Stine, J.D., director of federal relations for the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, told Psychiatric News that the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to people with incomes of up to 150 percent of the FPL would be “remarkable.”

The expansion would “strengthen Medicaid as a safety net for single, childless adults” who are generally ineligible for coverage under current rules at even the lowest income levels, she said.

Expanding access to Medicaid-covered mental health also could increase potential cost savings by providing people with treatment that prevents progression of minor psychiatric conditions into major ones that require expensive hospitalization or other costs to society.

The House bill also would require state Medicaid programs to cover preventive services not otherwise covered, if those services are recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Will It Be a Budget Buster?

Critics of the Medicaid expansion note that states hit by declines in tax revenues during the ongoing recession already are struggling to meet their existing Medicaid commitments. Federal assistance in covering some state obligations under Medicaid was provided under the Obama administration's stimulus bill enacted last February. But that funding is scheduled to expire at the end of this calendar year and along with it the requirement that states maintain eligibility levels and refrain from imposing enrollment barriers.

Despite the proposed eligibility expansion and federal stimulus assistance, states could cut programs and services that their Medicaid programs now fund as state budget outlooks deteriorate.

For instance, the Oklahoma Medicaid program is considering a range of cuts to produce a 5 percent budget drop, including reducing the number of brand-name prescriptions that adult beneficiaries can receive at any one time from three drugs to two.

The possible spending cuts many states are considering to balance declining revenue raise the prospect that states could roll back Medicaid eligibility expansions that they undertook during recent growth years.

The deteriorating fiscal outlook in Indiana led Gov. Mitch Daniels (R) to tell local media that his state cannot afford the proposed expansion of Medicaid, even if the federal government picks up 91 percent of the cost. However, some other governors in hard-hit states welcomed the possible Medicaid expansion and the larger federal cost sharing it would bring.

Physician Participation a Concern

Further state funding shortfalls also could worsen the payment shortcomings in the Medicaid system and reduce access to physicians. For instance, when the Kansas Medicaid program was recently faced with funding shortfalls, its administrators approved a 10 percent cut in all Medicaid provider payments.

Such reductions could affect the ability of physicians to treat an influx of new Medicaid patients when the programs pay, on average, only 60 percent as much as private insurance does, according to some estimates. The House bill would raise some physician Medicaid fees to the level of Medicare reimbursements.

The current low reimbursements have led to many physicians' refusing to see Medicaid patients.

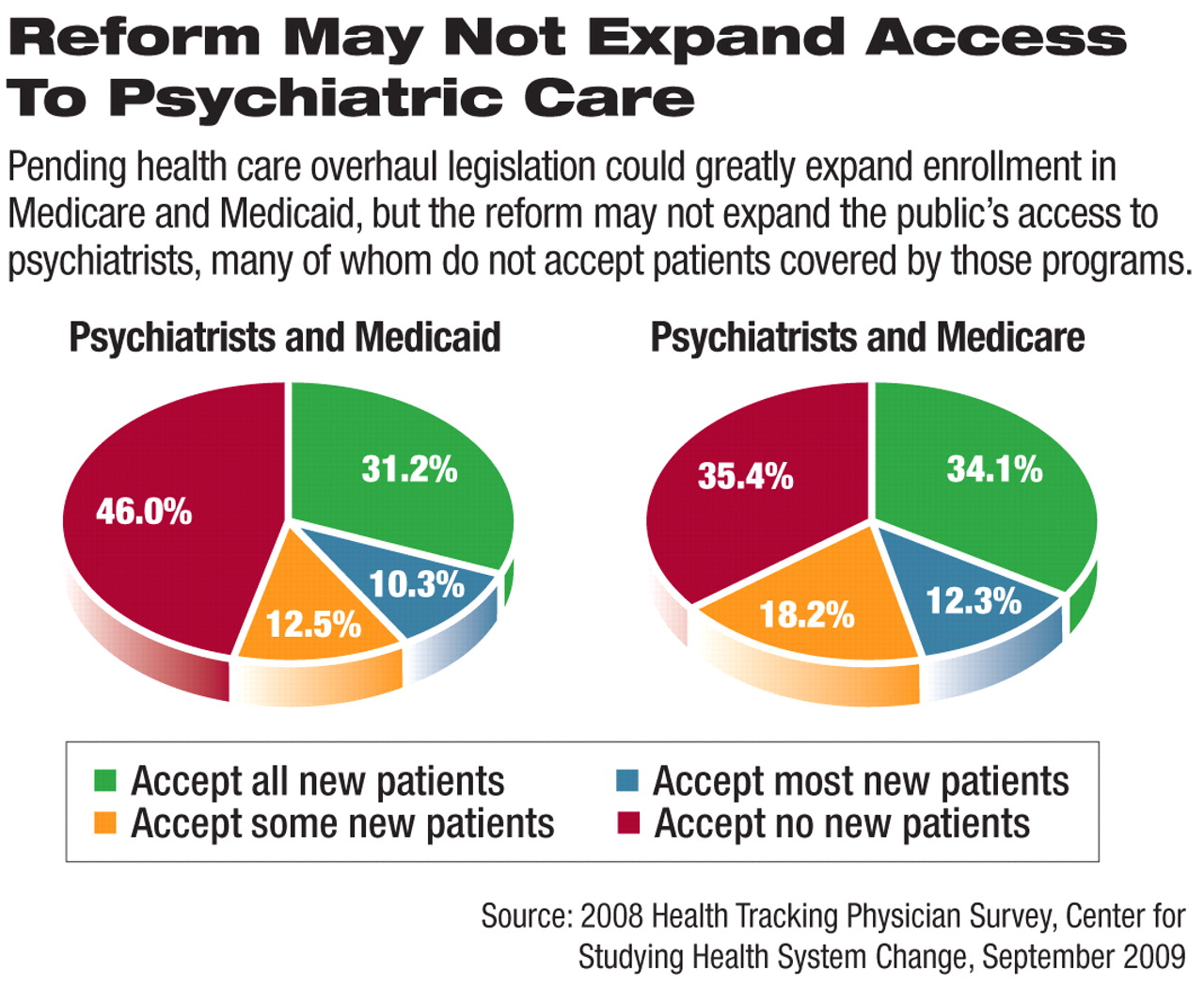

Research published in September 2009 by the Center for Studying Health System Change found that 28 percent of physicians don't accept Medicaid patients now, and 19 percent have limits on the number of Medicaid patients they will see. Forty percent of physicians said they will accept any Medicaid beneficiary.

That study found that psychiatrists were even more reluctant to accept Medicaid patients than the average physician, with 46 percent reporting that they are accepting no new Medicaid patients, while 23 percent of psychiatrists said they accept some or most Medicaid patients, and 31 percent accept all new Medicaid patients.