Lack of fear can precede criminal activity in adulthood. So suggests a study published online on November 16, 2009, in AJP in Advance and in the January American Journal of Psychiatry. The lead investigator was Yu Gao, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research associate in criminology, psychology, and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. Senior investigator was Adrian Raine, D.Phil., a professor in those departments.

Although lack of fear is already a well-established hallmark of antisocial individuals, this appears to be the first study to demonstrate that lack of fear early in life precedes criminal activity in adulthood.

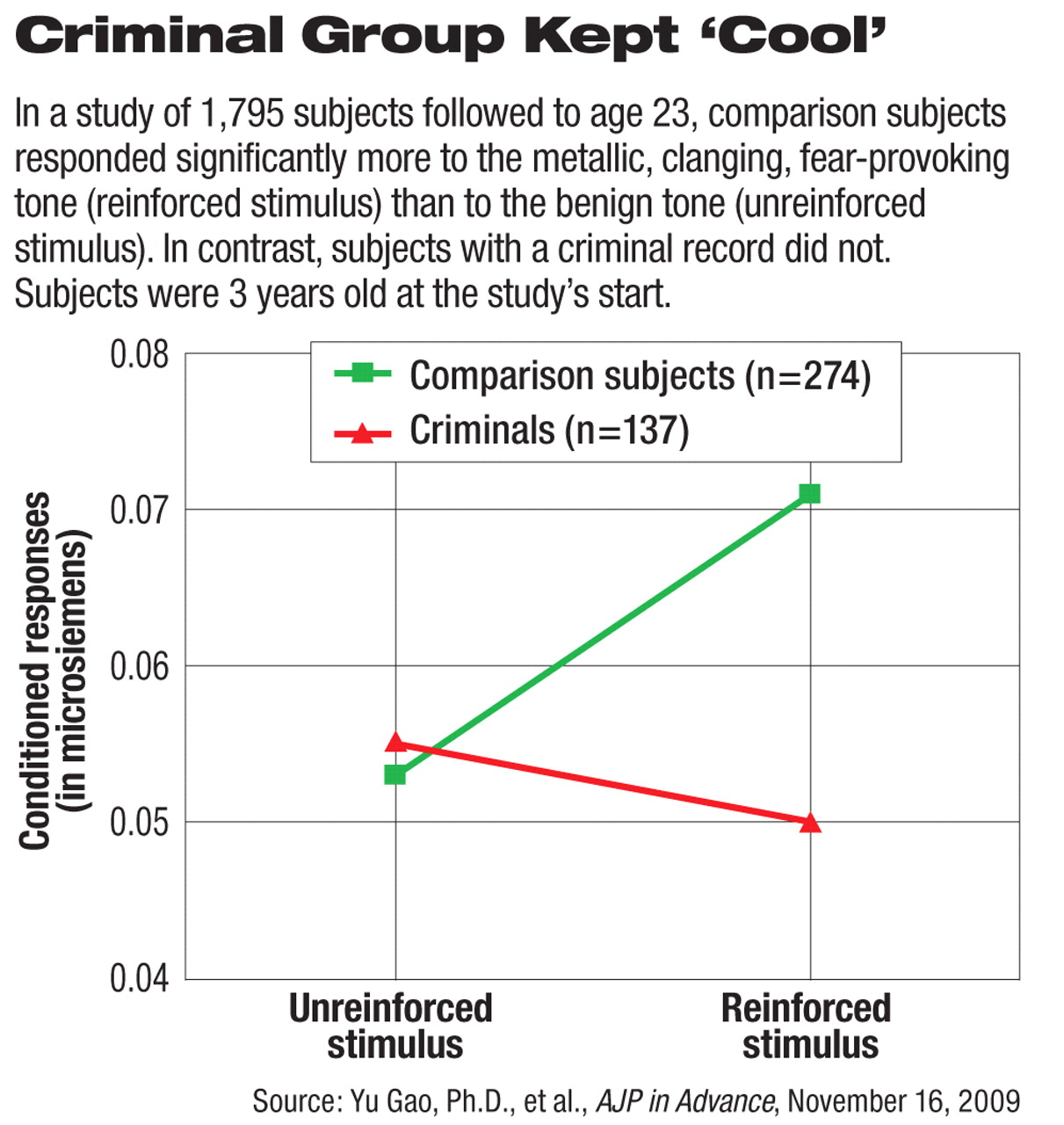

In the study, 1,795 children were exposed at age 3 to two different tones. One tone was coupled with a brusque, loud, metallic sound; the other tone was not. After the children had been exposed a few times to the two tones, they developed an aversive reaction to the tone coupled with the metallic sound. This was called “fear conditioning.”

After that, the electrical responses of the children's skin to the two tones were measured. Such responses reflected the involuntary nervous system's response to the stimuli.

After following the children to age 23, the researchers found that 137—or 8 percent of the cohort—had criminal records. Each of these 137 subjects was matched with two comparison subjects on gender, ethnicity, and social adversity. Finally, the researchers looked to see how the fear conditioning reactions of the subjects at age 3 compared with the fear conditioning reactions of the 274 adult comparison subjects.

Future Criminals Were Fearless

At age 3, the comparison group had shown normal fear conditioning—that is, a significantly greater reaction to the metallic, clanging, fear-provoking tone than to the benign one. In contrast, the group with criminal records had not. The results remained firm even when possibly confounding factors such as social adversity, ethnicity, or gender were considered.

Thus, “poor fear conditioning at age 3 predisposes to crime at age 23,” Gao and his group concluded.

“Poor fear conditioning [is simply a] proxy for amygdala dysfunction,” the researchers proposed in their paper. The amygdala is considered the primary brain structure for processing fear, and abnormal amygdala structure and function have been observed in both antisocial children and antisocial adults, they pointed out.

However, amygdala structure and function have not yet been visualized in children younger than age 11, the researchers noted. So “only when it becomes possible to conduct brain scans in large samples of very young children and follow them longitudinally over several decades will it be possible to confirm early amygdala dysfunction as a specific source of poor fear conditioning in young children who become adult criminal offenders.”

If the researchers are right, however, they believe that their findings suggest that neurodevelopment plays a role in antisocial or criminal behavior, especially since the amygdala, unlike some other brain structures, is rarely susceptible to injury or illness. And if that is the case, prevention may be possible.

Some Evidence Says Yes

Some provocative evidence amassed by David Olds, Ph.D., and colleagues, and cited by Gao and his team in their paper, suggests that it might. Olds is director of the Prevention Research Center for Family and Child Health at the University of Colorado in Denver.

For example, one of the studies conducted by Olds and his colleagues included some 400 disadvantaged pregnant women. Nurses helped half of them give their children a better physical and psychological start in utero and the first two years of life. The other half did not receive such help and served as controls. The children of both groups of women were followed to adulthood and compared. The offspring of the women who had received the intervention had experienced significantly fewer arrests and convictions than the offspring of the control women (Psychiatric News, August 1, 2008).

So it looks as though early-life interventions such as that tested by Olds and his team, or perhaps other interventions, such as nutritional enhancement, physical exercise, or cognitive stimulation, might be able to promote the normal development of brain structures involved in fear conditioning, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, Gao suggested to Psychiatric News. Further, if the amygdala and prefrontal cortex followed a normal developmental trajectory, it then might “facilitate the development of conscience and reduce [criminal] behavior,” he speculated.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, as well as the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust in the United Kingdom.