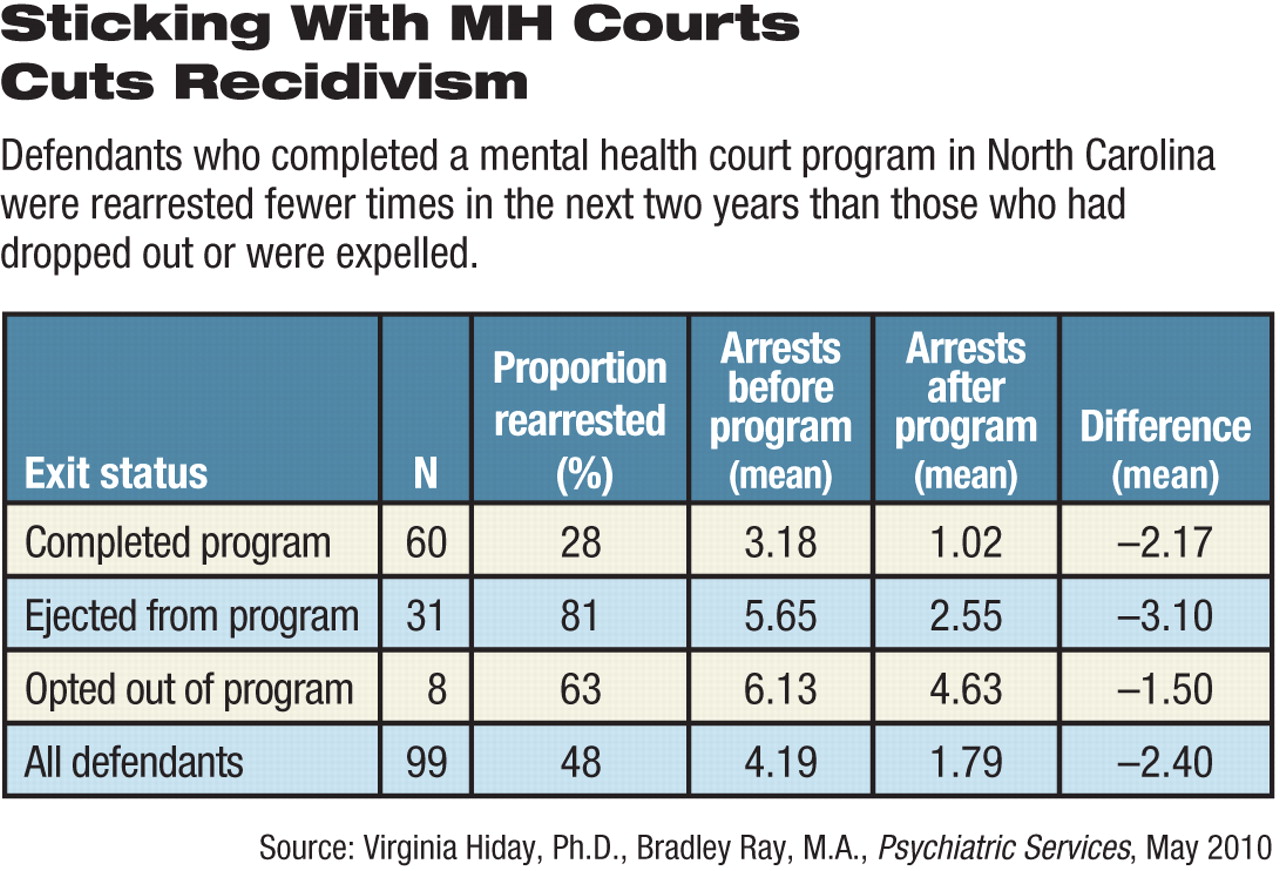

Criminal defendants who complete programs supervised by mental health courts are less likely to be rearrested in the following two years, according to a new study by North Carolina researchers appearing in the May Psychiatric Services.

About 72 percent of those who completed the program were not rearrested in that time, compared with just 19 percent of those who were expelled from the program and 37 percent of those who chose to leave, said Virginia Hiday, Ph.D., a distinguished professor of sociology and anthropology, and doctoral student Bradley Ray, M.A., both at North Carolina State University.

Also, more time passed before defendants who successfully finished the court process were rearrested, they wrote. For instance, at five months after the end of court supervision, only 8 percent of completers had been rearrested, compared with 46 percent of noncompleters.

The study adds to a small, but growing, body of research on mental health court outcomes. Future research into the psychological and demographic characteristics of those who enter such programs would help differentiate who does and does not complete them, said the authors.

Mental health courts serve as a voluntary alternative to either trial or sentencing for eligible defendants diagnosed with mental disorders. When successful, they keep such defendants out of jail.

“We need to find alternatives to putting people with mental illness in prison,” said Renée Binder, M.D., a professor and interim chair of the department of psychiatry and director of the Psychiatry and the Law Program at the University of California, San Francisco, in an interview. Binder has also published studies of mental health court outcomes, but was not involved in the North Carolina research.

In mental health courts, the judge supervises a nonadversarial, collaborative process in which a variety of professionals work with the defendant both to satisfy criminal justice requirements and to meet the individual's mental health needs. The team includes prosecutors, defense attorneys, social workers, mental and physical health clinicians, and employment, education, and housing specialists.

Hiday and Ray compared court administrative data and state arrest records for 99 defendants who left the local mental health court in 2005.

About 72 percent of the defendants were male and 65 percent were white. The 99 individuals entered the court with a total of 172 misdemeanor and 18 felony arrests.

The most common misdemeanor was assault (26 percent), and the most common felony violation was theft (83 percent).

Defendants who were eventually expelled from the program and those who opted out had much higher numbers of prior arrests than did completers.

That does not mean that they were more severely ill, said Hiday in an interview.

“Research has shown time and again that it is not any clinical factor such as severity of the mental illness that accounts for offending; rather, it is the same criminological factors that affect offending among others who are not mentally ill,” she said.

Of the 99 defendants, 60 completed the program in an average of just over a year. Of the 39 who did not complete the program, eight voluntarily left, and 31 were expelled for failing to show up for scheduled treatment or court appearances or for engaging in prohibited behavior, such as use of illegal drugs. Simply being rearrested did not mean that a defendant would be removed from the program, which explicitly acknowledged the possibility of relapse.

Contact with the mental health court was associated with fewer arrests regardless of whether the defendant completed the program. Overall, defendants had an average of 4.19 arrests in the two years prior to entering the program and 1.79 arrests in the two years afterward.

Defendants who completed the program were arrested on average only once in the following two years, and 72 percent of them were not rearrested. The percentages were reversed for the noncompleters: 81 percent of those who were expelled from the program and 63 percent of those who opted out were rearrested.

One of the limitations of this and similar studies on mental health courts is a lack of data about the symptoms and severity of mental illness among program participants at entry and following completion, as the authors noted.

Having that information would probably help identify which defendants have done well in mental health courts and which might do so in the future, said Binder.

“We really don't know what part of the process works,” she said. “Is it the contact with the judge, who has the authority to put the defendant in jail or keep him or her on the streets? Is it the constant contact with the court or some professional acting on its behalf? Is it the mobilization of many resources to help? Or is the person simply responding to a lot of positive attention?”

Hiday and Ray agreed. The North Carolina study was conducted in a single court, keeping that variable unchanged, they said.

However, defendant variables, such as substance abuse; having a supportive family, employment, more education, housing, and so on; lack of insight leading to unwillingness to acknowledge that they needed psychosocial help; motivation to change; and the quality and appropriateness of treatment were more highly correlated with completion and require further research, said Hiday.

She and Ray are continuing research into mental health courts, looking at the role of judges and how the defendants' psychological and social histories influence the courts' effects.