The nasty things that their peers say to them can not only hurt adolescents emotionally, but may also damage their brains and set the stage for psychiatric illness later, a new study suggests.

The study was headed by Martin Teicher, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Developmental Biopsychiatry Research Program at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. The report was tentatively scheduled for publication July 1 on the American Journal of Psychiatry's AJP in Advance Web site.

Teicher and his colleagues selected 707 late teens or young adults (aged 18 to 25) to participate in their study. None of the subjects reported having experienced domestic violence, sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, parental verbal abuse, or physical bullying by peers during childhood. So the researchers could examine peer verbal abuse independently of these other adverse experiences.

Teicher and his colleagues administered the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire, which contains 15 items and addresses various types of verbal abuse such as criticizing, belittling, blaming, insulting, demeaning, or ridiculing, to determine how many of their subjects had experienced peer verbal abuse during childhood or adolescence.

Nine percent had, they found. Furthermore, the bulk of peer verbal abuse transpired during the middle-school years, which generally includes youngsters aged 11 to 14. Males tended to have experienced verbal abuse from male peers, and females from female peers.

Teicher and his colleagues also had their subjects fill out several questionnaires—the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire, the Limbic Symptom Checklist-33, and the Dissociative Experiences Scale—to assess the participants' current psychological health. Then they looked to see whether there were links between having experienced peer verbal abuse during childhood or adolescence and current psychological problems.

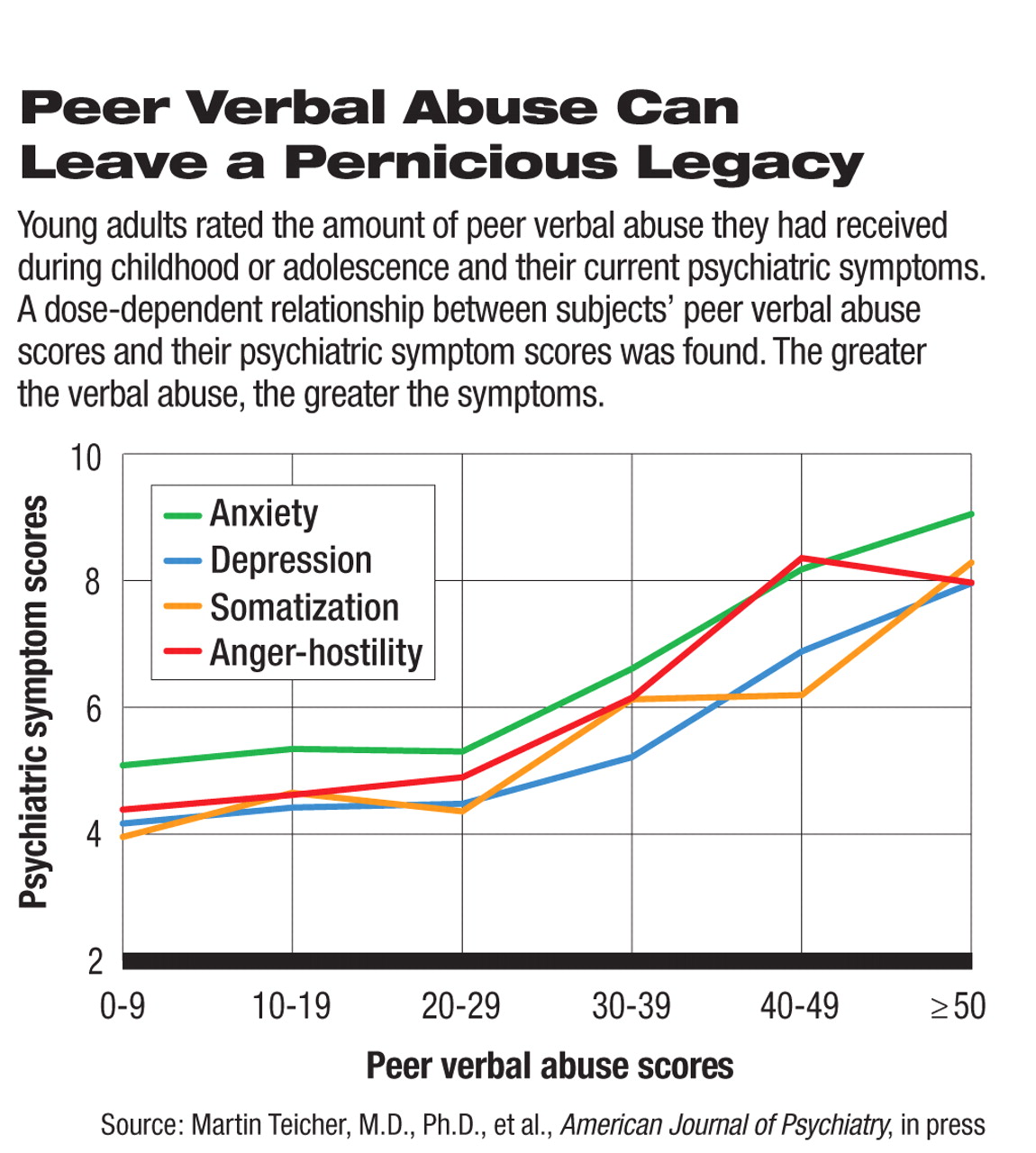

The researchers found that the more exposure to peer verbal abuse subjects reported, the more likely they were to be experiencing anxiety, depression, angerhostility, dissociation, or drug use at the time of the study. Peer verbal abuse during the middle-school years was found to be especially noxious in this regard.

Finally, the researchers obtained neuroimaging scans of a subset of their sample—63 young adults who had been exposed to varying degrees of peer verbal abuse. They wanted to see if they could find a significant link between subjects' exposure to peer verbal abuse during childhood or adolescence and damage to the corpus callosum.

They looked for damage in the corpus callosum because it connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain, it contains nerves that carry nearly all the neural traffic to and from the cerebral cortex, and types of maltreatment other than verbal abuse had already been linked with corpus callosum damage. In other words, the researchers believed that if they could document corpus callosum damage in subjects who had experienced peer verbal abuse, it might explain why these subjects subsequently experienced psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, anger-hostility, dissociation, or drug use.

Indeed they did find evidence of corpus callosum damage in their verbal-abuse subjects. So it looks as if peer verbal abuse can lead to damage in the corpus callosum, and corpus callosum damage in turn can increase the risk that young people will experience psychological problems.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, NARSAD, and donations from the Simches and Rosenberg families.

“Hurtful Words: Exposure to Peer Verbal Aggression Is Associated With Elevated Psychiatric Symptom Scores and Corpus Callosum Abnormalities” is posted at <http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org> under “AJP in Advance.”