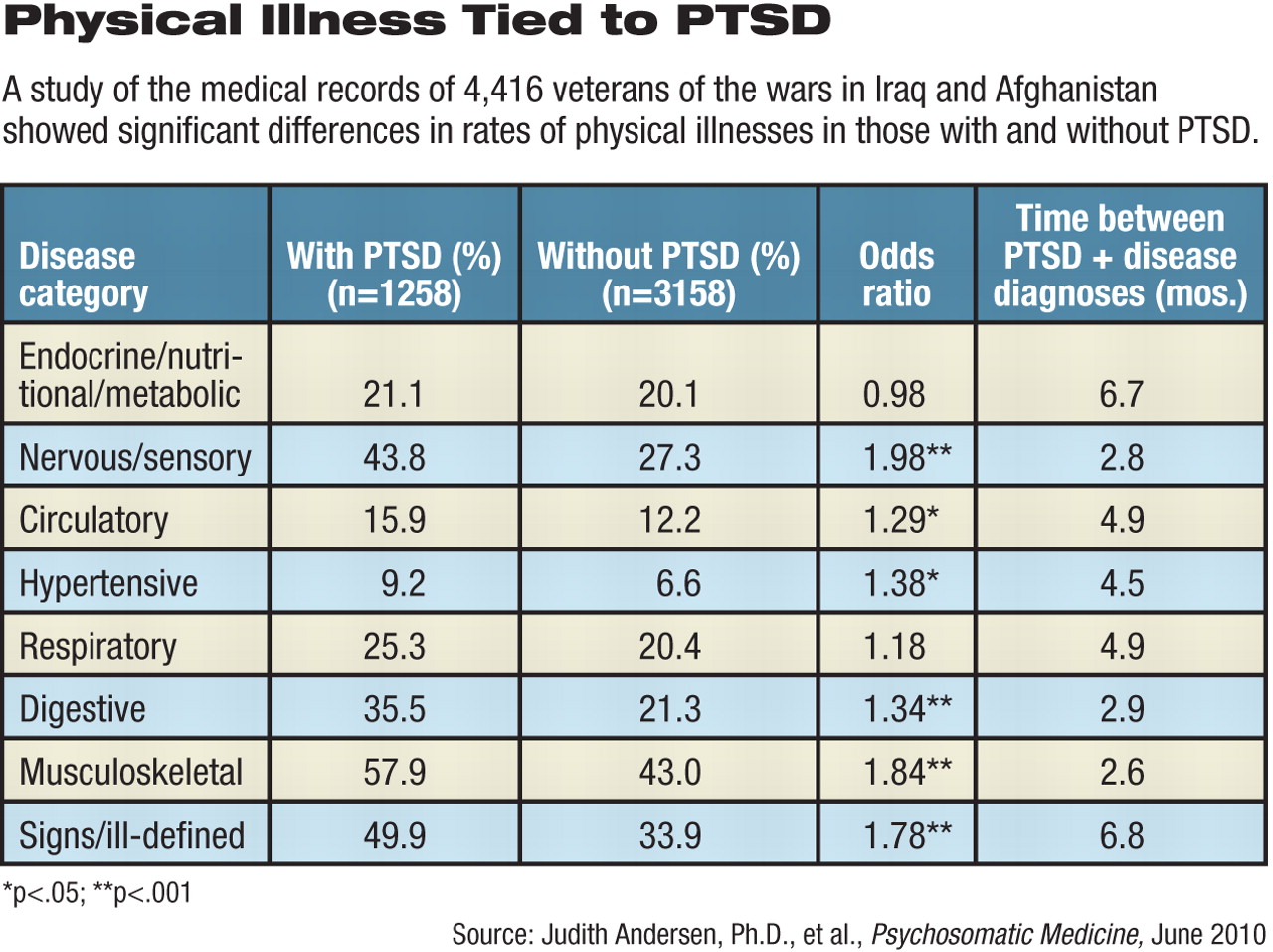

Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have higher-than-usual rates of several physical ailments, according to a study of 4,416 such veterans.

The diagnosis in primary care settings of physical disorders in these combat veterans came only three to seven months after they received a PTSD diagnosis.

“What is particularly striking about these findings is that diseases traditionally considered to develop across the lifespan (e.g., circulatory system and hypertensive conditions) appeared shortly after the end of military service,” wrote Judith Andersen, Ph.D., and colleagues from the Center for Integrated Healthcare at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Syracuse, N.Y.

Veterans of recent conflicts may thus be subject to increases in “lifespan morbidity, mortality, and health care utilization in the coming years,” they pointed out.

“I'm not surprised by the findings,” commented Joseph Boscarino, Ph.D., M.P.H. “But I am surprised at how quickly these problems showed up. I thought it would take another five or 10 years.”

Boscarino is senior investigator at the Geisinger Center for Health Research in Danville, Pa, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Temple University. He has researched the effects of PTSD on physical illness among Vietnam War veterans, but was not involved in the present study.

Andersen and colleagues examined the VA medical records of service members who had served in “zones of imminent danger” from September 11, 2001, to December 31, 2007. They were screened for mental and physical conditions when they entered the VA system and annually thereafter.

The average age of the participants was 29; 85 percent were white. Roughly half (53 percent) had served in the active-duty components of their service, while 47 percent were National Guard or reserve veterans.

At entry, 277 (6 percent) of the 4,416 participants were diagnosed with PTSD. Over the six-year study, 1,031 (24.6 percent) of the veteran participants received a PTSD diagnosis. Patients were followed for an average of about 17 months.

The researchers adjusted initial results for covariates such as age, gender, marital status, depression, substance use disorders, and unit type.

They found that a PTSD diagnosis was associated significantly with a 56 percent increased risk of hypertensive disease, a 36 percent increased risk of circulatory disease, a 24 percent increased risk of digestive disease, an 81 percent increased risk of nervous system disease, and a 70 percent increased risk of “ill-defined signs and symptoms,” compared with veterans who did not have PTSD.

No increased risk of respiratory or endocrine, nutritional, or metabolic illnesses was observed, they noted.

PTSD is a “unique contributor to disease” even after controlling for depression, substance abuse, and other factors known to affect physical-illness onset, the authors said.

The study was not designed to determine causality. Several theories have been suggested to explain a causal relationship between PTSD and development of physical disease, but there is widespread agreement that many factors are involved.

These include substance abuse, preexisting vulnerabilities, and changes in the stress axes and in hormones affecting the immune system.

“It's hard to sort out what causes some people to get PTSD and others not, even when exposed to the same traumatic events,” said Boscarino. “We always thought there would be multiple pathways.”

One big question for clinicians is whether early treatment of PTSD and these physical illnesses would contain the damage they cause, he said. Interventions instituted shortly after trauma might ultimately improve the quality of life and save money in future treatment costs, he noted.

Andersen and colleagues argued for early intervention after deployment to lessen the impact of PTSD on general health, and Boscarino agreed that this is a strategy worth pursuing.

“Even some types of psychoeducational program in the war zones would keep memories from getting fixed through the amygdala,” Boscarino said. Such brief therapies apparently helped many 9/11 victims, but few clinical trials have been carried out to test the efficacy of these early therapies.

However, no one wants to wait years or decades while memories engrave themselves in the brain before intervening to help affected veterans, as happened with so many who served in Vietnam, he said.