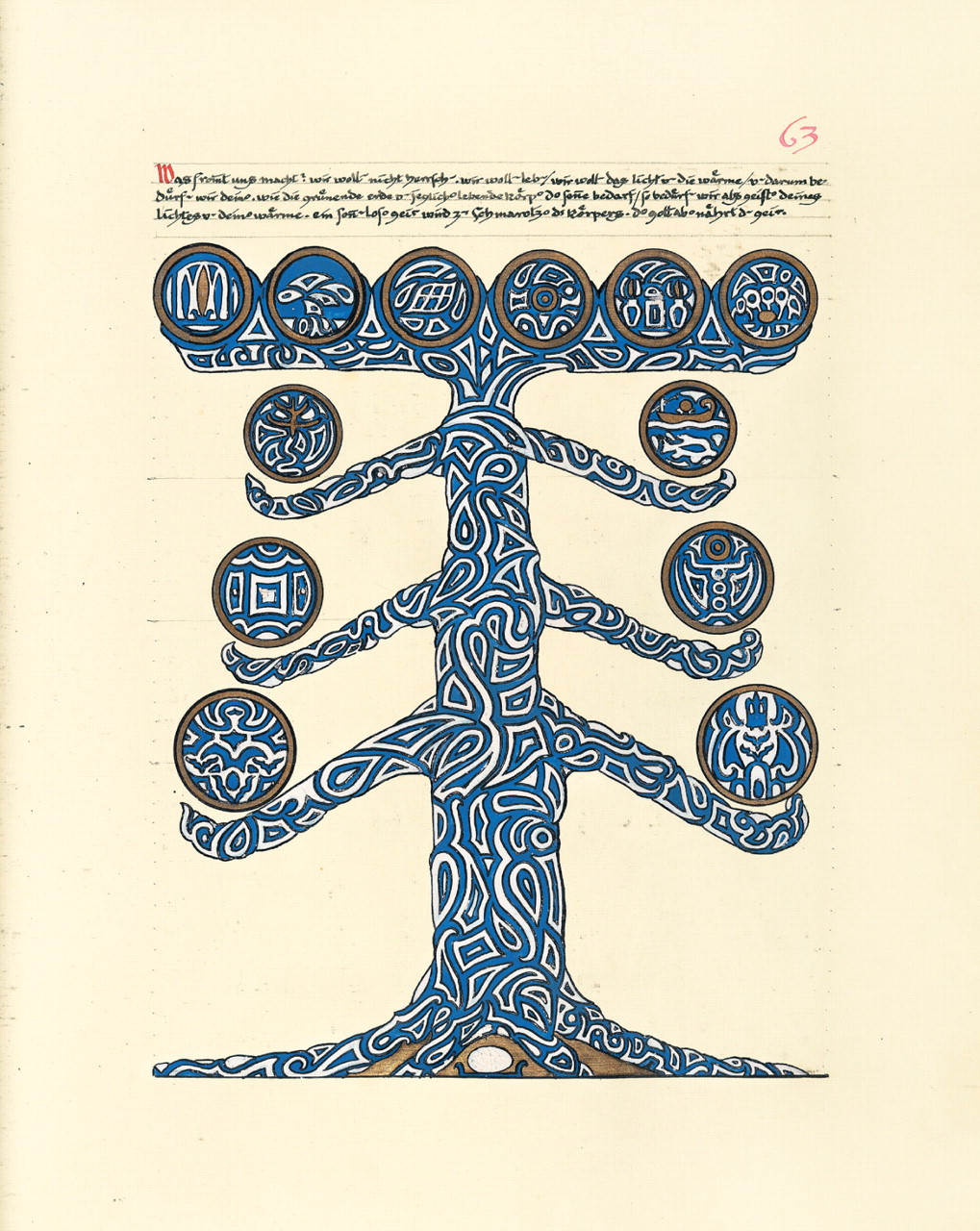

The book rests alone in a display case in a darkened room. Hand-drawn illustrations reminiscent of medieval manuscripts glow from the pages. Page after page of precisely lettered text in a foreign language crawls across slim, penciled guidelines.

One might think this was a religious shrine awaiting a stream of believers, if the room weren't in the Library of Congress, next to the books collected by that eminent rationalist, Thomas Jefferson.

Yet perhaps it is a shrine of sorts.

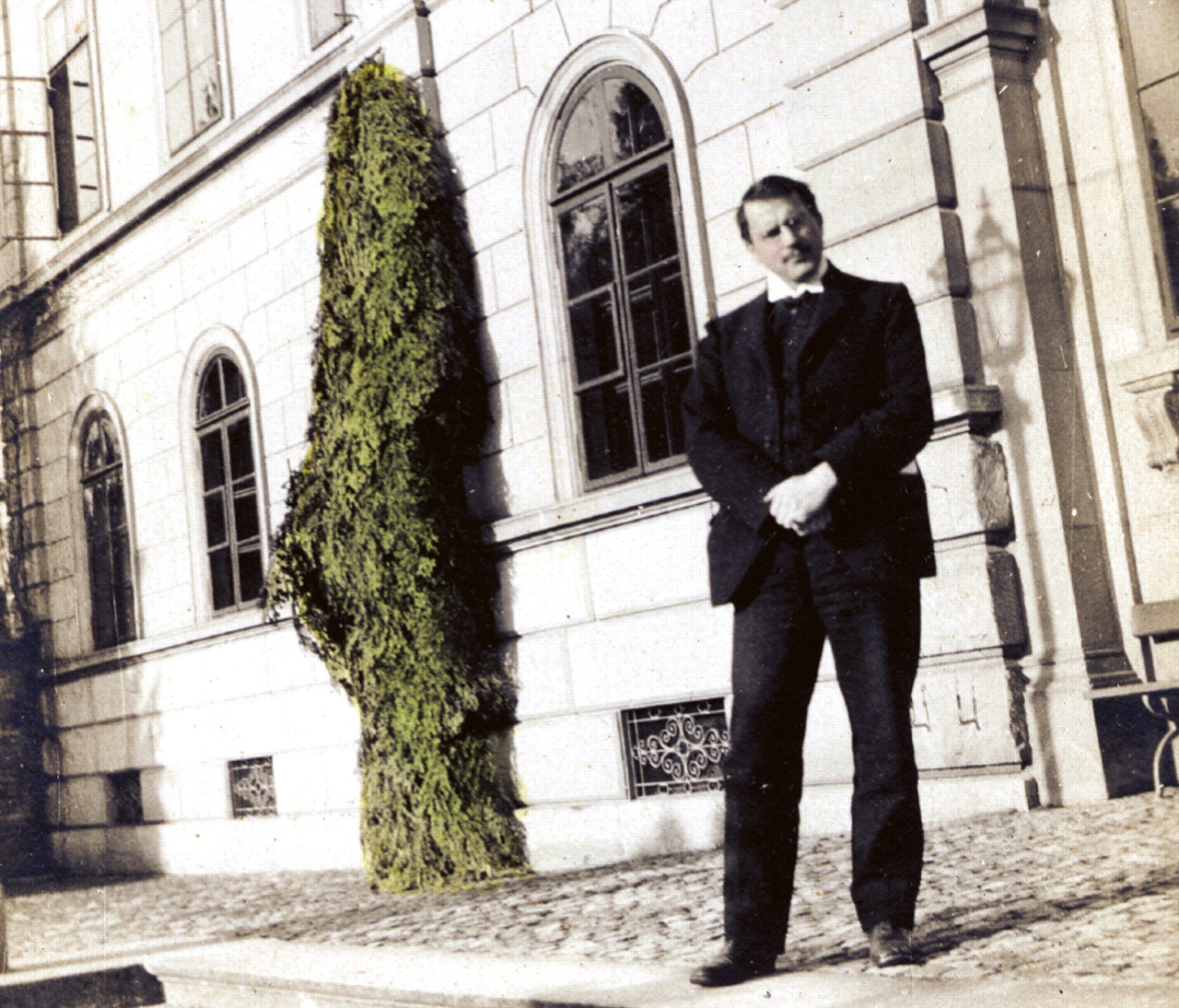

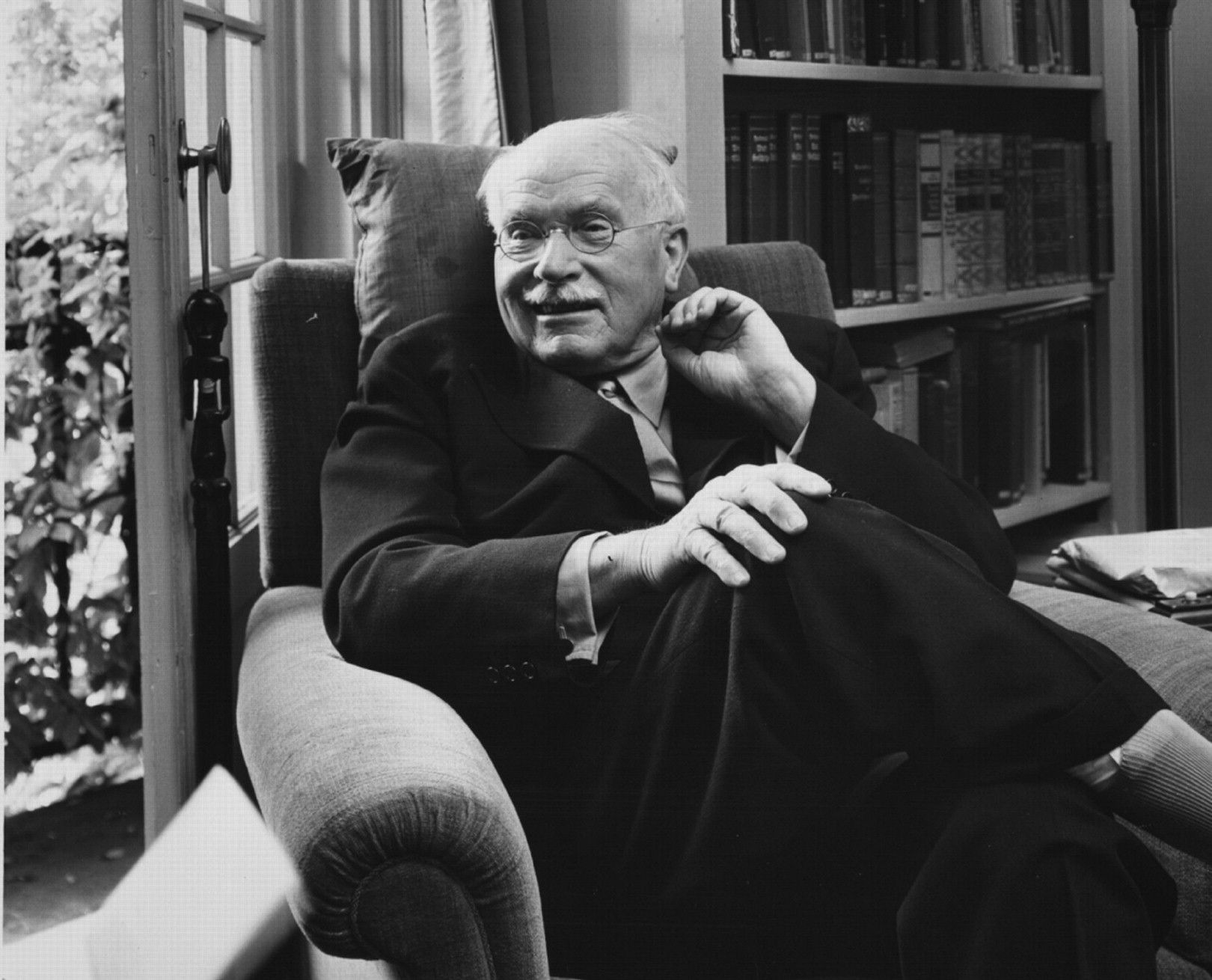

The volume is the long-discussed but—until recently—rarely seen Red Book, the intensely private work of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, M.D. (1875-1961).

Jung devotees had speculated on the book's contents, but few had seen it since Jung created it just prior to World War I. The material is so personal that Jung's heirs denied access to the manuscript until 2001.

One clue to the mysterious book's origins lies in a note Jung wrote in his copy of Dante's Commedia: “In the middle of the journey of my life, I found myself at a place where the straight road had been lost sight of.”

This midlife crisis led him into months of intense creative work on what he first called the “Liber Novus,” or “new book.”

Jung's technique, which he called “active imagination,” involved recalling dreams and then evoking visions and fantasies in a waking state. He amplified these images with parallels drawn from what he called the collective imagination of humankind, as expressed in myths, religious beliefs and practices, visions, alchemy, and yoga, according to Ernest Falzeder, Ph.D., a lecturer at Austria's University of Innsbruck, who spoke at a symposium at the Library of Congress in conjunction with the exhibit.

From November 1913 to April 1914, Jung's extended jottings were “frequent exercises in the emptying of consciousness,” as he wrote in his notebook. The process seemed so radical to him that he later said that he thought he might be on the verge of schizophrenia.

After that initial stretch of creativity, Jung used his notes to write an expanded first draft. About half the material in the draft came from the dream notebooks.

Deriving Principle From Fantasy

“[H]e attempted to derive general psychological principles from the fantasies and to understand the extent to which events portrayed in the fantasies presented, in symbolic form, developments that were to occur in the world,” wrote Sonu Shamdasani, Ph.D., the Philemon Professor of Jung in the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London, in the introduction to the Red Book (W. W. Norton, 2009), which he also edited.

The book describes a descent into hell, a journey that makes a recurrent appearance in the Western tradition, like Odysseus's journey into the underworld and Jesus's descent into hell after the crucifixion, Shamdasani said at the symposium.

The content does appear to prefigure world events. Visions of blood, destruction, and death abound, so Jung was actually relieved when World War I broke out on August 1, 1914, because he decided that his fantasies were about Europe and not himself.

Jung had the draft typed, then revised it. He inscribed a final version onto parchment and illustrated the text with his own paintings. Some images referred to the words but others were independent and symbolic. The colors, sometimes accented with gold paint, remain vivid today on the original pages in the exhibit.

He ordered a specially made red-leather binding, which gave the work its present title—the Red Book.

Idea Translated Into Patient Care

All the while that he was working on the Red Book, Jung continued with his professional work. The two tasks were not separate in his mind. He suggested to his patients that they, too, try the technique of exploring their imaginations and thinking about what they envisioned.

Jung saw dreams not as codes to be deciphered for their hidden meanings as Sigmund Freud believed, but as source material for psychotherapy to be accepted at face value, said James Harris, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, pediatrics, and mental hygiene at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and art and images editor of Archives of General Psychiatry.

“Jung used imaginal techniques to solve problems, like using play therapy with children,” said Harris in an interview with Psychiatric News. He has taught Jung's ideas in his classes for 30 years.

Thus, while the Red Book is not a work of science, it affected Jung's views on psychology and influenced his followers in the decades to come.

Archetypal imagery that expresses universal human experiences may be little used in treating major mental illness today, but it has had a wide-spread effect on literature, art, music, and theology, among other fields. The exhibit includes references to the works of choreographer Martha Graham, filmmakers George Lucas's “Star Wars” and Federico Fellini's “8½,” and author Jorge Luis Borges.

Besides the chance to see the long-suppressed Red Book, the exhibit offers insight into the history of psychiatry, said Harris.

Freud at one point considered Jung his successor as the leader of the psychoanalytic movement, but that image of a master/protégé relationship distorts their actual relationship, he said.

Jung introduced a number of basic terms and ideas into psychology—“complex,” “introversion,” “extraversion,” “countertransference,” and others—that have become identified with Freud, said Harris. “Perhaps publication of the Red Book will stimulate a reconsideration of Jung separately from Freud.”