The record rate of suicides among U.S. Army soldiers can be traced not only to the stress of multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, but also to high-risk behavior, lower recruitment standards, lax discipline, and stigma, according to Army Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Peter Chiarelli.

At a press conference in late July, Chiarelli released a 350-page report that went well beyond earlier internal studies that focused more on individual risk factors for suicide.

Chiarelli said that he hoped the report would be seen as “an attempt by the United States Army to take a really, really hard look at itself [and] see some things that maybe we're not doing as well as we should ... in the context of a force that's been fighting for 10 years.”

The more comprehensive view in the report may benefit the service if its numerous recommendations are accepted, said a former Army psychiatrist.

“Until now, isolated groups have only been looking at sub-elements of risk,” said Stephen Xenakis, M.D., a retired brigadier general now in private practice in Arlington, Va., and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. “By being as detailed as it is, the report will prompt the Army into changing its culture.”

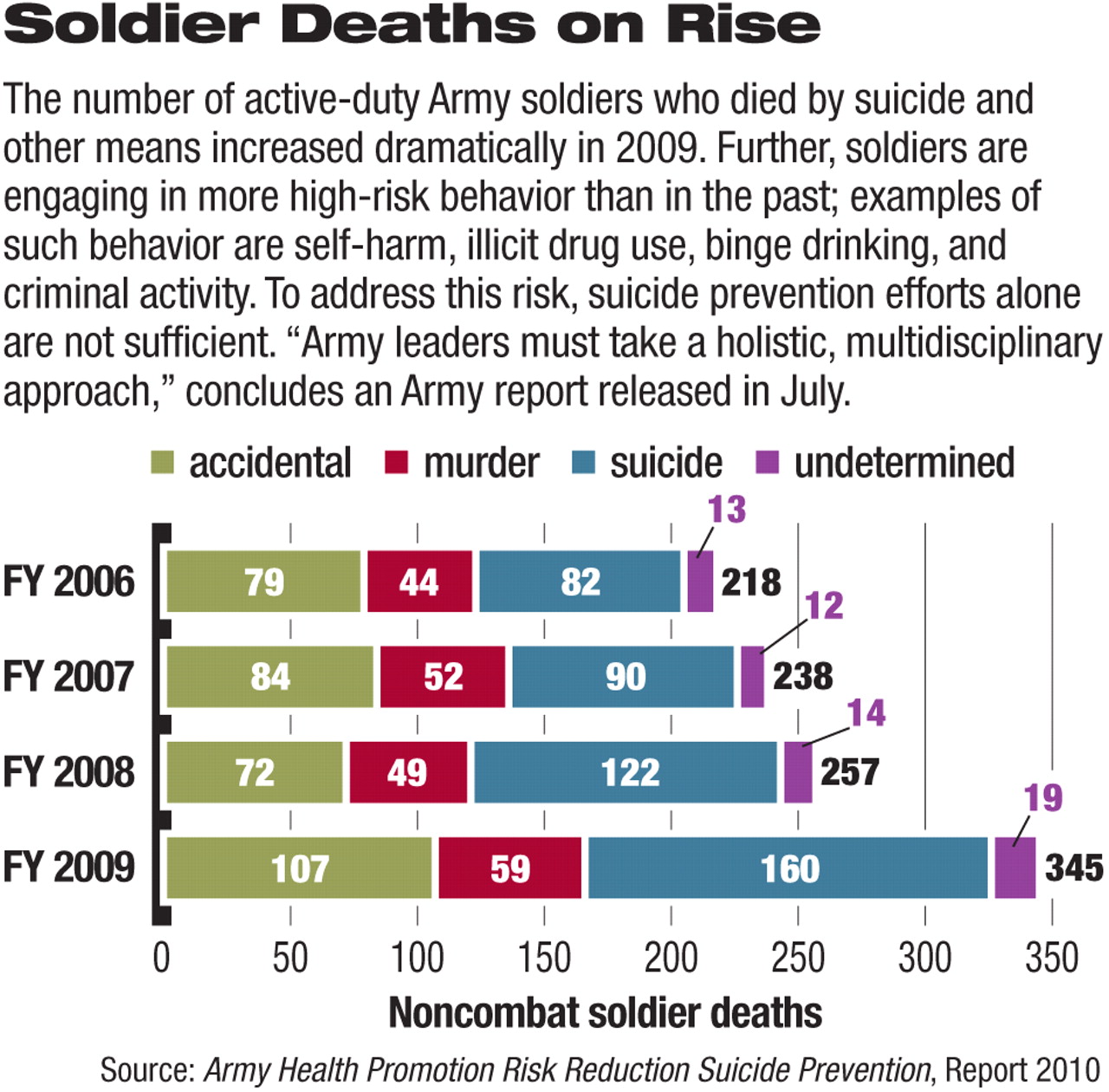

The Army had 160 active-duty suicide deaths in Fiscal 2009, plus 79 suicide deaths of Reserve and National Guard soldiers. The Army suicide rate reached a new peak in 2008, with a rate of 20.2 per 100,000, for the first time rising above the demographically adjusted civilian rate of 19.2 per 100,000.

There were also 146 active-duty deaths attributed to high-risk behavior, including 74 drug overdoses.

In total, those numbers added up to more than all Army combat deaths in 2009.

In the past, the Army has focused its attention on the circumstances surrounding suicides. They have primarily involved relationship or work problems, recorded in 58 percent and 50 percent of 2009 suicides, respectively.

But other risk factors have also been identified—youth, for one.

“The most dangerous year to be a soldier is your first year in the United States Army,” Chiarelli said. Sixty percent of suicides occur during the first enlistment term, when most soldiers are in their late teens or early 20s. Recent research shows that these younger soldiers, said Chiarelli, “have a much lower rate of resiliency ... than older members.”

Age predicts an even more vulnerable cohort of soldiers, those who enlist in their late 20s. Their suicide rate is triple that of their younger comrades, possibly because they face many existing stressors prior to entry, he said.

“I think it's fair to say in some instances that this would be a soldier who's married, [with a] couple of kids, lost his job, no health care insurance, possibly a single parent ... coming into the Army to start all over again,” he said.

In response, the Army has instituted 10 hours of resiliency training for new soldiers.

However, factors other than the personal circumstances of individual soldiers were associated with suicide.

For a time, to boost enlistments, the Army issued more waivers to allow the enlistment of recruits who were not high school graduates, had brushes with the law, or had behavioral or emotional problems, including drug use. Those enlistment standards have been tightened again in recent years, but a significant minority of soldiers continues to violate Army policies on drug and alcohol use or other misconduct.

The report also notes that young people who join the Army in wartime may have a greater risk tolerance than their civilian peers, leading to more risky behavior while in the service.

“Unfortunately, we have identified a troubling subset of our population who increasingly place themselves at risk,” wrote Chiarelli. “This cohort includes soldiers who refuse help, use [or] distribute illicit drugs, and commit crimes.”

There were nearly 75,000 criminal offenses in the Army, including 17,000 related to drugs and alcohol in 2009, he said.

Such problems are more manifest at home bases than they are in the war zones, said Chiarelli. The Army would like to be able to keep soldiers at home between combat assignments for two years after they deploy for one year in Iraq or Afghanistan, but this standard will not be reached until at least 2012.

With a relatively short time at home, unit commanders focus on training for combat before or between deployments. To keep unit numbers up to strength, they are less likely now to request discharges for problematic soldiers, even some who commit crimes. Also, recent changes in the command structure have separated base administration from combat leadership, leaving some disciplinary processes in limbo.

Lieutenants, captains, and sergeants walk a fine line between disciplining soldiers with drug or other problems and encouraging them to seek help.

Yet another problem is the Army's surprisingly loose control over prescription drugs, which has led to abuse. For instance, a soldier prescribed an opiate for pain may continue filling the prescription long after the pain has resolved and may continue using the medication recreationally or sell it to other soldiers. If the soldier fails a drug test during that time, the existence of the prescription would deflect any further investigation of drug abuse. Putting an end date on the prescription would help cut down on such behavior, he said.

The Army needs more drug and alcohol counselors, since there were more than 225,000 behavioral health contacts last year, Chiarelli noted. Also, it must continue working to eliminate the stigma attached to seeking help and to train commanders to recognize problems early in a soldier's enlistment and tackle those problems before they balloon into serious mental health problems.

“We want to take a hard look at every soldier that comes back [before] they demonstrate that high-risk behavior [and] try to identify those who are going to have a rough time early on so we can get them the help they need,” said Chiarelli.

The report's analysis and recommendations may reflect a broader shift in thinking about mental health concerns.

For the past 15 or 20 years, the disease model of psychiatry has been dominant in determining treatment, in and out of the military services, and has led to a reliance on medication over psychosocial considerations, said Xenakis.

“That obscured the fact that mental health is more complicated and involves social, personal, and community factors, as well as neurophysiological ones.

“The report lays out a culture change for the Army and the need to create effective and sophisticated community mental health plans.”