Enactment of the Americans With Disabilities Act 20 years ago this summer and subsequent court decisions defining its scope have provided critical legal support for many people with serious mental illness. But even as recent court rulings continue to expand the law's support for community-based care for people with serious psychiatric illness, the measure has had little impact on several key areas in the lives of many with mental illness.

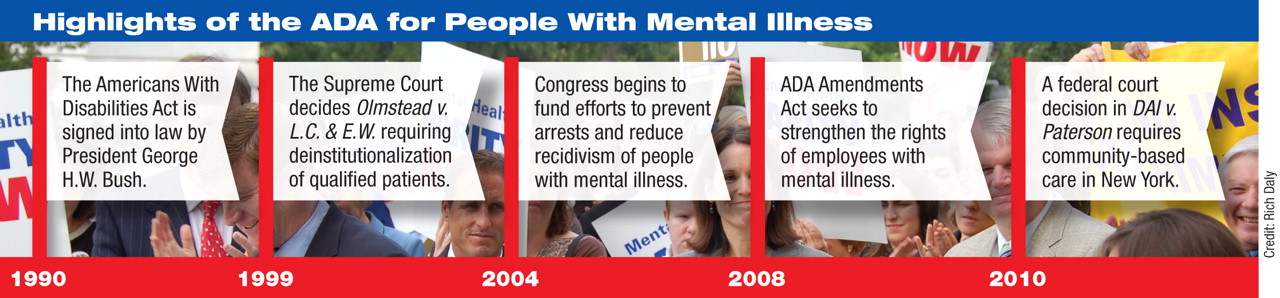

Signed into law in July 1990 by President George H.W. Bush, the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) sought to protect people with physical or mental disabilities from the discrimination they often endured. The law initially defined a disability as any condition that impairs one or more major life activities, and its definition was expanded in 2008 to include chronic health conditions specifically.

Enforcement of the law initially focused on improving access for people with physical disabilities to public places and transportation and sought to raise public awareness about the challenges faced by people with disabilities. And it has had a lasting impact on those areas, according to responses of people self-identified as having a disability, in a recent survey sponsored by one of the architects of the law. However, the law's impact on people disabled by a mental illness—who numbered more than 16 million by 2005, according to the U.S. Census Bureau—did not gather steam until a Supreme Court decision nine years after the measure was enacted.

The 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Olmstead v. L.C. & E.W. concluded that long-term institutionalization of people with mental illness deemed capable of independent living violated their rights under the ADA.

The ADA and Olmstead combined to become “enormously important for people institutionalized with serious mental illness,” said Susan Stefan, a retired attorney and author of Hollow Promises: Employment Discrimination Against People With Mental Disabilities, which examined federal courts' interpretations of the ADA.

Some mental health advocates worry that the promise of Olmstead has failed to materialize because many of the people who remain institutionalized want to move to community housing with treatments provided. However, the Olmstead decision at least has allowed legal advocates to achieve improvements through class-action suits on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis (Psychiatric News, August 7, 2009).

The ADA's legal framework also has been used to improve conditions for prison inmates with mental illness, including multiple judicial decisions ordering increased numbers of mental health staff and availability of treatment in state and local prison systems. The ADA “is very helpful in encouraging states to find treatment for prisoners with mental illness, and that's significant because there are a lot of those types of prisoners,” said Robert Fleischner, an attorney at the Center for Public Representation, who has litigated many mental health prison-law cases, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Legal advocates have especially focused on applying the law's protections to prisoners who are sent to solitary confinement, often as a result of behavior stemming from untreated mental illness (see

Psychiatrists Decry Punishment That Isolates Prisoners; also,

Psychiatric News, March 7, 2008).

Ruling Expands Law's Scope

A major follow-up victory to Olmstead was the March 1 federal court ruling in Disability Advocates Inc. v. Paterson (DAI v. Paterson), which ordered New York state to provide all qualified publically funded adult-home residents with an opportunity to move into supported housing, where they can receive mental health and social services in their own apartments and homes. The DAI ruling moved beyond Olmstead's focus on psychiatric hospitalization and found that New York's adult homes did not meet the ADA's requirement that disabled residents cared for by the state be allowed to live in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs.

“Until DAI, a lot of advocates thought that the law had fallen short of the promise of Olmstead because the courts had been applying Olmstead narrowly,” said John Petrila, a professor in the Department of Mental Health Law and Policy at the University of South Florida, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “This could set up a big expansion of community-based care.”

People with psychiatric illness housed in institutional settings also have benefitted from the more aggressive enforcement of the ADA by the Department of Justice (DoJ) under the Obama administration. Thomas Perez, assistant attorney general in the Civil Rights Division, told senators at a hearing in July that Olmstead enforcement was a “top priority” that has led the DoJ to undertake Olmstead-related legal action in 10 states over the first 18 months of the new administration.

The DoJ has changed its approach to investigations of institutions' compliance with federal civil rights laws from merely investigating whether institutions are safe to now asking whether their patients could appropriately receive services in a more integrated setting (Psychiatric News, August 6).

Justice Department ‘More Sympathetic’

“The DoJ is now more sympathetic to those claims,” Petrila said about legal actions to enforce the Olmstead ruling in institutional settings.

Another effort to strengthen the ADA in recent years came with the 2008 enactment of the Americans With Disabilities Act Amendments Act, which clarified the ADA and sought to offer greater protection for disabled employees. Specifically, the 2008 measure sought to address problems that disability-rights advocates saw in four Supreme Court decisions issued from 1999 to 2002, which narrowly interpreted the ADA in favor of employers.

Mental health advocates said that the ADA amendment law would improve the integration of people living with mental illness into the workplace.

Some Protections Still Missing

Although the ADA has mandated significant protections for people institutionalized with psychiatric illness, legal advocates are disappointed that other critical areas of the nation's laws appear untouched by it.

Stefan noted that state and federal courts continue to terminate parental rights of some people with psychiatric illness on the belief that they are incapable of caring for their children.

“The way that judges refer to these people is how they used to refer to people with physical disabilities,” Stefan said.

The problem is exacerbated by similarly biased views of parental competency among allied mental health workers within the child-protection system, she said. The result is that many parents—especially mothers—won't seek needed psychiatric care for fear that it will be used as grounds for their children's removal.

Another area in which the ADA's promise of additional protections for people with psychiatric illness has fallen short is in their interactions with law enforcement. A combination of a lack of understanding about mental illness among police and an increase in the number of people with psychiatric conditions as a result of the deinstitutionalization movement has led to many injuries and deaths by police.

In response to this problem, a growing number of police departments have launched training programs and instituted specialized units to de-escalate and peacefully resolve situations involving people in mental health crises (Psychiatric News, November 20, 2009). However, that law-enforcement change has been largely independent of the ADA and its legal framework, so its impact is highly localized to the jurisdictions undertaking such reforms, noted Stefan.

Temporary Illnesses Excluded

Other shortcomings related to ADA enforcement, according to disability rights advocates, are limitations courts have placed on employee protections for workers with some forms of psychiatric illness. For instance, the Supreme Court ruled in 2002 that the ADA does not cover disability related to temporary medical conditions or exacerbations of existing illnesses, even if those flare-ups could be considered disabling. Since mental illnesses are often characterized by occasional recurrences and remissions, they could be excluded from ADA protections. Even the 2008 amendments to the law excluded protection for “transitory” illnesses, which it defined as lasting less than six months.

Although no major legislative changes to the ADA are under consideration in Congress, disability-rights advocates may push for further strengthening in the future.

“Much work remains to fulfill the promise of the ADA. Our challenge today is to deconstruct the systemic barriers that sustain segregation,” said Robert Bernstein, Ph.D., executive director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. “The Bazelon Center is working closely with the U.S. Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to ensure that the ADA's benefits extend to all people with serious mental illnesses in all facets of their lives.”