Patients with mental illness consistently face longer emergency room (ER) visits for both treatment and referral to psychiatric facilities than do people with other types of illness or with injuries.

These findings, published in the September Psychiatric Services, provide the first quantitative confirmation of years of anecdotal reports by people with mental illness that they face extended delays in care when they go to an ER.

“These are people whose wounds are not visible and thus appear less sick, but who are actually quite sick,” said Lisa Dixon, M.D., M.P.H., an author of the study and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “They are not going to [be seen] in front of someone who comes in with chest pains or who comes in bleeding, but their wounds are actually the equivalent of that, and they are made to wait in uncomfortable circumstances for uncertain [lengths of] time.”

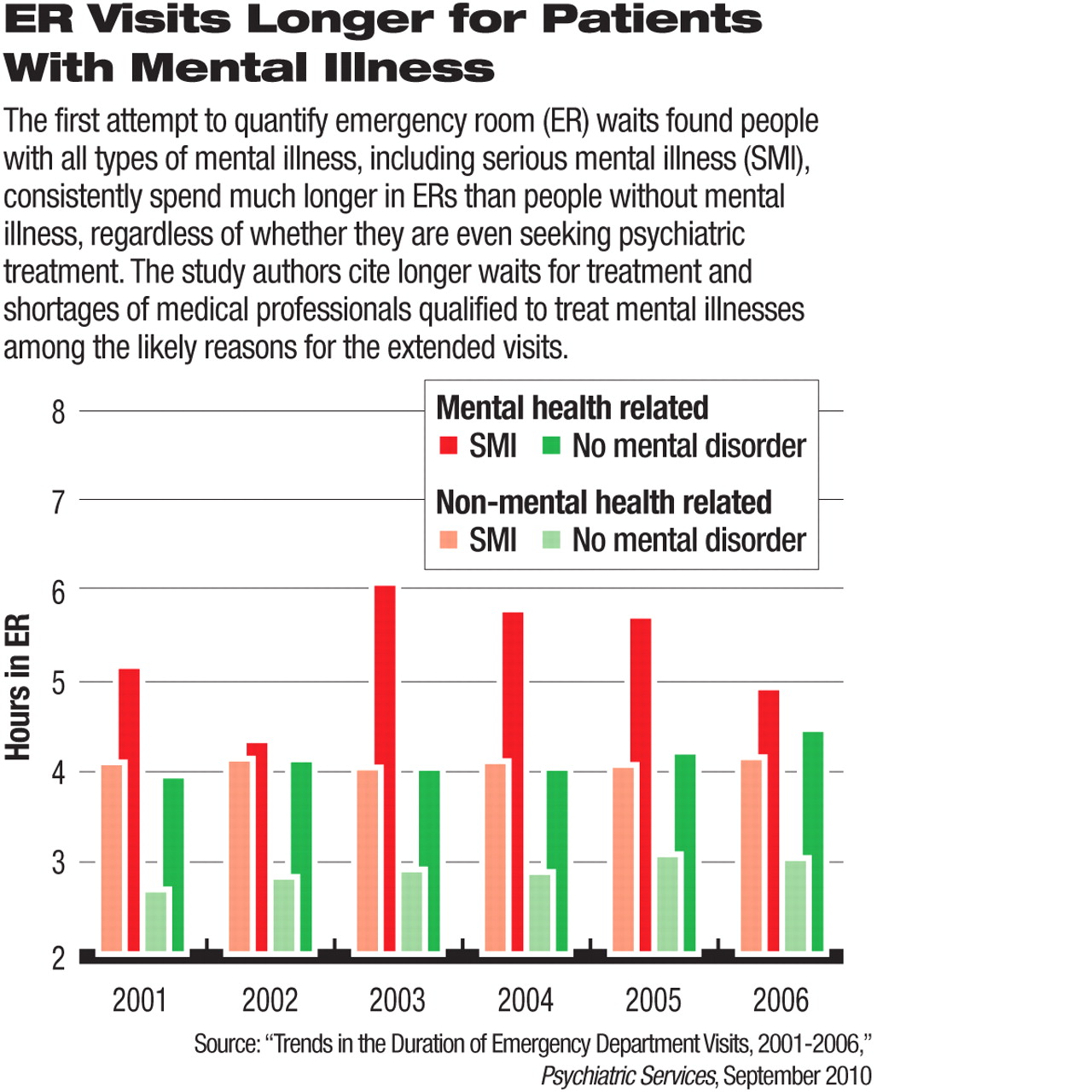

The study, based on an analysis of national hospital ER database records from 2001 to 2006, found that the average duration of mental health visits was 42 percent, or 1.25 hours, longer than the average three-hour duration of visits not related to mental health. The longer visit durations were attributed in large part to longer waits for care due to shortages of mental health clinicians in many ER settings.

And among people with mental health concerns appearing in the ER, those with substance use disorders were particularly likely to endure longer ER visits, with their average ER times 33 percent longer than for those with other mental illness issues.

Additionally, the study found that the duration of ER visits related to mental illness was especially long if the patients were diagnosed with a severe mental illness or eventually referred to a psychiatric facility, such as a substance abuse treatment center.

Data Support Anecdotal Reports

These findings validate the “lore out there that mental health and substance use patients spend particularly long periods of time in the ER for a variety reasons,” Eric Slade, Ph.D., a co-author of the study and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News.

Slade and Dixon said the available data were insufficient, however, to explain precisely why people with mental disorders faced longer times in hospital ERs, but they agreed that likely causes included continuing shortages of mental health clinicians and a shrinking number of psychiatric treatment beds.

Another factor in extended ER times could be enactment of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act in 1986, which aimed to improve the care provided to people with mental illness. The law required ERs to stabilize patients before transferring them and to not transfer based only on a lack of health insurance. However, hospital ERs must complete extensive paperwork showing that they have complied with those provisions of the law before the transfer is undertaken, which can add “extensive waits,” said Dixon, who is also deputy director of the Department of Veterans Affairs' Capitol Health Care Network.

“It makes the situation very complicated, especially when people need to be transferred or even admitted,” Dixon said.

Uncertain Impact of New Laws

What remains uncertain, however, is the impact of recent major changes in the nation's health care policy on the duration of patient stays in hospital ERs, the researchers agreed. The newest data used in their study are from 2006, and major laws enacted since then—such as federal mental health insurance parity requirements and health insurance reform—could affect the length of ER visits.

However, Dixon and Slade said the situation resulting from changes in the law is equally likely to have improved or deteriorated.

“Anecdotally, I would probably say it's gotten worse” since 2006, said Slade, about the growing number of news reports over the last year about extended ER wait times.

Dixon, though, maintained that the health care overhaul could eventually lessen ER congestion by helping more people obtain insurance coverage and therefore gain access to nonemergency treatment before an untreated psychiatric condition deteriorates to the point that emergency care is required.