When the FDA decided on a labeling change for antiepileptic drugs in 2008 to warn about increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior, epilepsy specialists raised concerns that the warning could lead patients to discontinue their medication, or primary care physicians to become reluctant to treat patients in need of these drugs and thus result in more harm than benefit.

The FDA decision was based on a meta-analysis of data gathered by drug companies in the course of premarket studies designed to gain approval for 11 medications. In brief, suicidal ideation and behavior occurred in 0.43 percent of patients taking an antiepileptic drug, compared with 0.22 percent of those on placebo in those trials (Psychiatric News, February 6, 2009).

Critics noted, however, that all the drugs were lumped together in one class, despite varied mechanisms of action. In addition, two drugs, valproate (which has a different mechanism of action) and carbamazepine, were associated with less suicidality than placebo, and no data were presented for another, frequently prescribed drug, phenytoin.

“The problem with the FDA meta-analysis is that it was based on spontaneous reports,” said Andres Kanner, M.D., a professor of neurological science and psychiatry at Rush Medical College in Chicago and a spokesperson for both the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. “The FDA warning started a debate on the reliability of its data.”

The debate is complicated by the fact that epilepsy alone doubles suicide risk, said Kanner. About 10 percent to 15 percent of those whose epilepsy is poorly controlled have suicidal ideation after a seizure. Those diagnosed with both epilepsy and depression face 32 times the risk of committing suicide than those with neither and a greater risk than those with depression alone.

Furthermore, people with epilepsy have an increased risk of psychiatric disorders, and people with a suicidal history are five times more likely to develop epileptic seizures than the general population, suggesting possible pathogenic mechanisms common to both epilepsy and depressive disorders, he said.

Since 2008, epidemiologists have been combing through various databases to more accurately ascertain any relationship between use of antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. Several studies have been published recently, with mixed findings.

A study of 112,000 patients over age 66 by Anne VanCott, M.D., an associate professor of neurology at the University of Pittsburgh, and colleagues from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Neurology Division, found that “the most important predictive factor of suicidality was a diagnosis of affective disorder prior to initiation of [antiepileptic drug] monotherapy treatment.” However, only 64 individuals had displayed suicide-related behaviors, and the researchers said that larger clinical populations, in all age groups, will be needed to sort out the relationship between the drugs and suicidality.

In April, Elisabetta Patorno, M.D., M.P.H., of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics in the Department of Medicine at Harvard's Brigham and Women's Hospital, and colleagues, published an “exploratory analysis” of 269,937 patients aged 15 and older in the HealthCore Integrated Research Database. There were 801 attempted suicides, 26 completed suicides, and 41 other violent deaths in that cohort. Patorno and colleagues found increased risk for events in new users of gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and tiagabine compared with topiramate.

However, Kanner noted three problems with the study. It did not consider the indications for the drugs, and it did not address prior risk factors, especially suicide attempts, he said. “And they found that topiramate produced the least suicidality, contrary to our experience in the clinic.”

Researchers who conducted a study published in July in Neurology divided drugs prescribed to 44,300 patients with epilepsy drawn from the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database into four groups: barbiturates, conventional antiepileptic drugs, newer antiepileptic drugs with low potential for causing depression, and newer antiepileptic drugs with high potential for causing depression. Only the last group (including levetiracetam, tiagabine, topiramate, and vigabatrin) was associated with an increased risk (threefold) of self-harm or suicidal behavior. However, all the added risk for that category derived from just two cases among patients using levetiracetam.

Even that increased risk was “only evident in patients with, but not those without, psychiatric comorbidity,” wrote Frank Andersohn, M.D., of the Institute for Social Medicine, Epidemiology, and Health Economics at the Charite-University Medical Center in Berlin, and colleagues in the July Neurology.

“Andersohn confirmed what we have known all along, although he didn't include prior suicide attempts in his analysis even though a prior attempt is a major risk factor for completed suicide,” said Kanner.

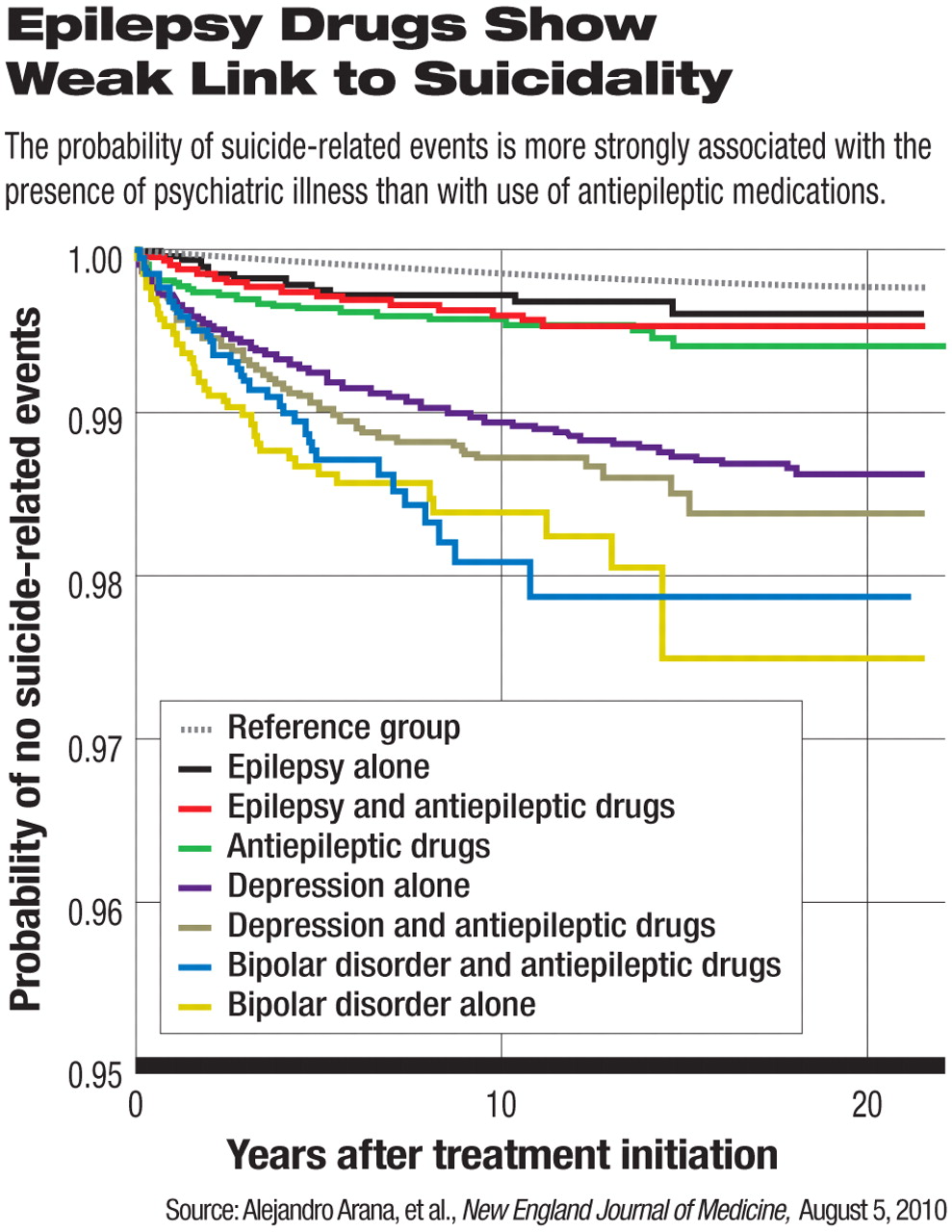

In August, another study appeared, one covering about 5.1 million British patients. Alejandro Arana, M.D., of Risk MR Pharmacovigilance Services in Zaragoza, Spain, and colleagues concluded that comorbid psychiatric conditions, rather than use of antiepileptic drugs in people with epilepsy, were more often associated with suicidality.

“The current use of antiepileptic drugs was not associated with an increased risk of suicide-related events among patients with epilepsy [odds ratio, 0.59], but it was associated with an increased risk of such events among patients with depression [OR, 1.65] and among those who did not have epilepsy, depression, or bipolar disorder [OR, 1.65],” wrote Arana and colleagues in the August 5 New England Journal of Medicine. Indications for the use of antiepileptics in patients without epilepsy, depression, or bipolar disorder were not known.

In sum, said Kanner, antiepileptic drugs do increase the risk of suicidality, but rarely and more often in people with psychiatric risk factors.

He noted that the risk of suicide in people with epilepsy results from a complex relation between the two conditions. A few, but definitely not all, antiepileptic drugs may increase the risk of suicidality by causing psychiatric adverse events. This is likely to happen in people who already have psychiatric risk factors.

“This, however, should not detract physicians from using antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of their patients,” he said. “So it is extremely important to learn if patients have a prior personal or family history of psychiatric illness. Physicians must use greater caution with such patients in the choice of some of these medications.”