People with severe mental illness die decades sooner, on average, than those without such illnesses, and one of the reasons may be that many are heavy smokers.

People with mental illness account for 44 percent of the tobacco market in the United States. Many are strongly addicted. About 68 percent of people with schizophrenia who smoke light up more than two packs a day.

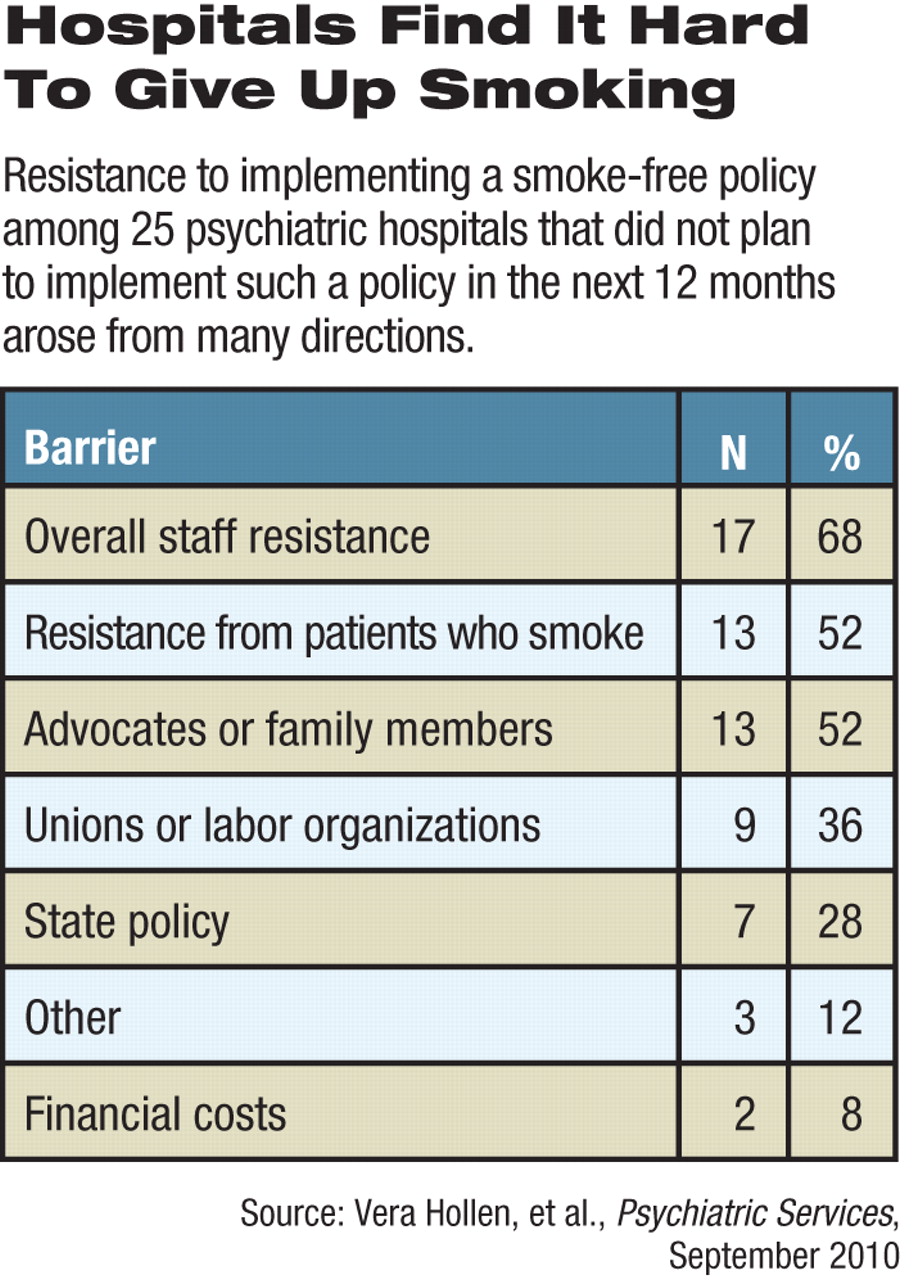

Yet it has not been easy to curb smoking in public psychiatric hospitals, according to researchers from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute. They reported their findings in the September Psychiatric Services.

Their survey of 70 psychiatric hospitals where smoking was permitted in 2006 found that only 28 had changed their policies to ban smoking entirely by 2008.

Only four of the remaining 42 permitted smoking indoors, while the rest allowed patients or staff to puff away somewhere outdoors on hospital property.

Smoking by people with mental illness has long been a contentious issue.

“Silently and insidiously tobacco sales and tobacco smoking became an accepted way of life not only in our society, but also in our public mental health treatment facilities,” stated a 2006 position paper by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD).

Despite clear health benefits that derive from smoking bans, resistance to such bans at psychiatric facilities comes from both patients and staff members.

Fear of adverse events is often listed as a reason not to ban smoking completely, said Vera Hollen, M.A., and colleagues in their Psychiatric Services report. Their survey found that staff members worried that without cigarettes patients would be more aggressive, and staff smokers would be unhappy. Survey respondents also said that smoking reinforced the therapeutic bond between patients and staff.

“Smoke breaks became an ‘entitlement,’ deserved and protected, and are one of the only times [patients] can practice relating to each other and staff in a ‘normalized’ way,” said the 2006 NASMHPD statement.

However, Hollen and colleagues found no increase in adverse events at psychiatric institutions that banned smoking.

Of the 28 hospitals that changed their policies to become smoke free, tobacco-related health problems, seclusion and restraint, and use of coercion or threats all declined significantly, they said. Hospitals that did not adopt a smoke-free policy still saw fewer adverse events involving threats or coercion among patients and staff, according to Hollen.

Some who object to tobacco bans at state psychiatric hospitals argue that smoking is an individual right. However, one major advocacy group suggested that there may be other points to consider before forbidding patients to smoke.

“The real challenge, as it is elsewhere in the mental health field, is sustainability,” said Ron Honberg, J.D., director of policy and legal affairs for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

NAMI's policy is to support and encourage smoke-free treatment facilities, he said. However, withdrawal from tobacco addiction is hard enough without attempting it during a psychiatric crisis.

“When hospital stays were longer, you could work on broader health concerns with patients,” Honberg told Psychiatric News. “But if they are only in for several weeks and then leave, it is much harder to stay off tobacco afterward without some linkage in the community.”

Also, the effects of forcing a patient to quit smoking on that patient's psychiatric condition are unknown, he said.

Honberg also believes that tying a drop in adverse events to a smoking ban may be premature.

“A reduction in adverse incidents can be due to a number of factors, like staffing levels or training or patient characteristics,” said Honberg, who found the new study's results “mildly encouraging.”

All of the hospitals responding to the survey, regardless of whether they implemented smoking bans during the study period, offered nicotine-replacement therapy or smoking-cessation medications to help staff and patients quit smoking. The only statistically significant difference over the two years was that the institutions that went smoke-free more often offered pharmacotherapy to those who wanted to quit in 2008 than was the case in 2006.

No such difference was observed in the number of hospitals offering nicotine-replacement therapy, possibly because an antismoking drug (bupropion) is available on hospital formularies, while nicotine-replacement therapies are often not.

Smaller hospitals appeared to have had more success in changing policies, most likely because their size led to better communication among management, staff, and patients, suggested the authors.

Communication may be the key to a successful transition to a smoke-free hospital, they concluded.

“Hospitals must be proactive by involving advocates, families, and unions before, during, and after a smoking-policy change,” they said. “Any major policy change must also include a patient-education component.”