When surgeons in the United States make a major medical error, it is more likely related to burnout and depression than to the frequency of overnight call or the number of hours worked.

So suggest the results of a survey commissioned by the American College of Surgeons and headed by Tait Shanafelt, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic. Results were published online November 19, 2009, in the Annals of Surgery.

In June 2008 Shanafelt and his colleagues sent the survey via e-mail to some 25,000 members of the American College of Surgeons. A cover letter stated that the purpose of the survey was to better understand the factors that contribute to surgeons' career satisfaction. So that surgeons' responses would not be biased, nothing was said about the specific mission of the survey—to see whether there was any link between surgical errors and burnout or depression.

The survey asked each surgeon to provide demographic information, practice characteristics, whether he or she had made any major medical errors within the previous three months, and if so, why. The survey also included standardized tools to measure the surgeon's mental and physical quality of life and to determine whether he or she was experiencing burnout or depression.

Some 7,900 surgeons, about 32 percent of those receiving the survey, completed and returned it.

Nine percent of the participating surgeons reported having made a major medical error within the previous three months. General surgeons were most likely to report such errors, while ear surgeons, plastic surgeons, and obstetric/gynecologic surgeons were least likely to do so.

Shanafelt and his coworkers then looked to see whether the errors that these surgeons had made could be linked with the number of nights on call per week, the number of hours worked each week, or with burnout and depression, while taking some possibly confounding personal and professional factors into consideration.

Neither the frequency of overnight call nor the frequency of hours worked was linked with surgical errors. However, burnout and depression were.

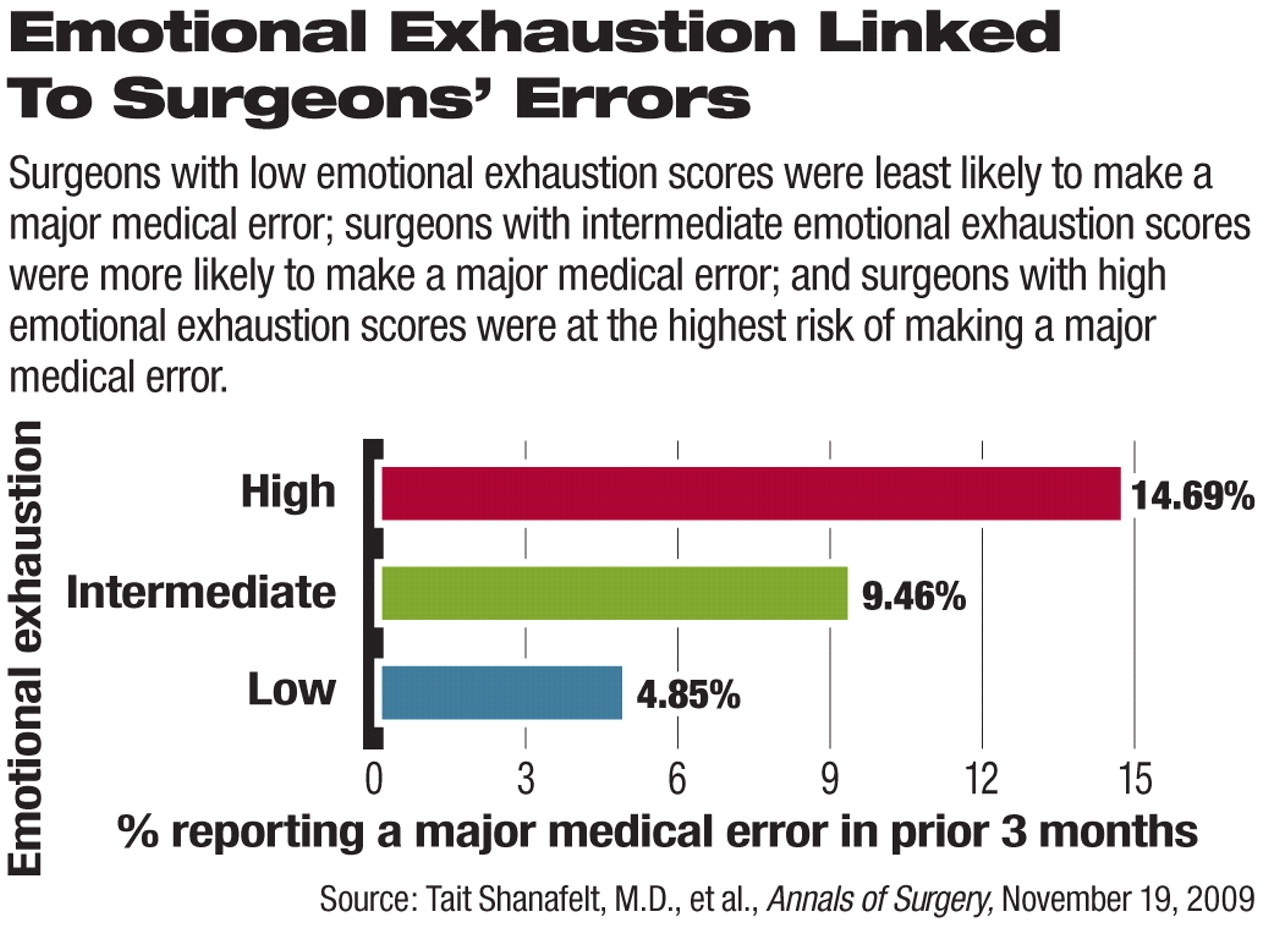

Reporting a surgical error during the prior three months had a large, statistically significant adverse relationship with mental quality of life; all three domains of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment); and symptoms of depression. Each one-point increase in depersonalization was associated with an 11 percent increase in the likelihood of reporting having made an error, while each one-point increase in emotional exhaustion was associated with a 5 percent increase in such likelihood.

Thus, “major medical errors reported by surgeons are strongly related to a surgeon's degree of burnout and their mental quality of life,” Shanafelt and his group concluded.

The question, then, is why? Since the survey was of a cross-sectional nature, it did not reveal whether surgeons' burnout and depression contributed to their errors or vice versa. However, previous research that he and his colleagues conducted suggests that it works both ways, Shanafelt told Psychiatric News.

But either way, “studies are needed to determine how to reduce surgeon distress and how to support surgeons when medical errors occur,” he and his group pointed out.

In fact, their survey may provide some answers to these two questions, Shanafelt said, since it also explored both use of and barriers to accessing mental health resources by surgeons and how decisions to use those services relate to burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation. Results from this analysis are in press with the Archives of Surgery.