Say “rural” to most Americans and you'll conjure up images of cornfields or rugged mountains, but in the 50th state, the distance is filled with the blue Pacific Ocean.

Hawaii's psychiatrists and mental health professionals, like those in many states, are concentrated in metropolitan areas, which means the state capital, Honolulu. But two psychiatrists provide examples of different ways to bring care to the Aloha State's far-flung residents.

One was born in Honolulu but detoured through Harvard long enough to become a Red Sox fan. The other is a native of New York State who found a distant island on a sailing trip and decided to stay.

Chad Koyanagi, M.D., is the hometown doctor, now the medical director of the inpatient unit at Queen's Medical Center in Honolulu and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Hawaii's John A. Burns School of Medicine.

His mission is to increase access to mental health care in the state's rural areas, improve its quality, collaborate with local providers, and help develop the workforce.

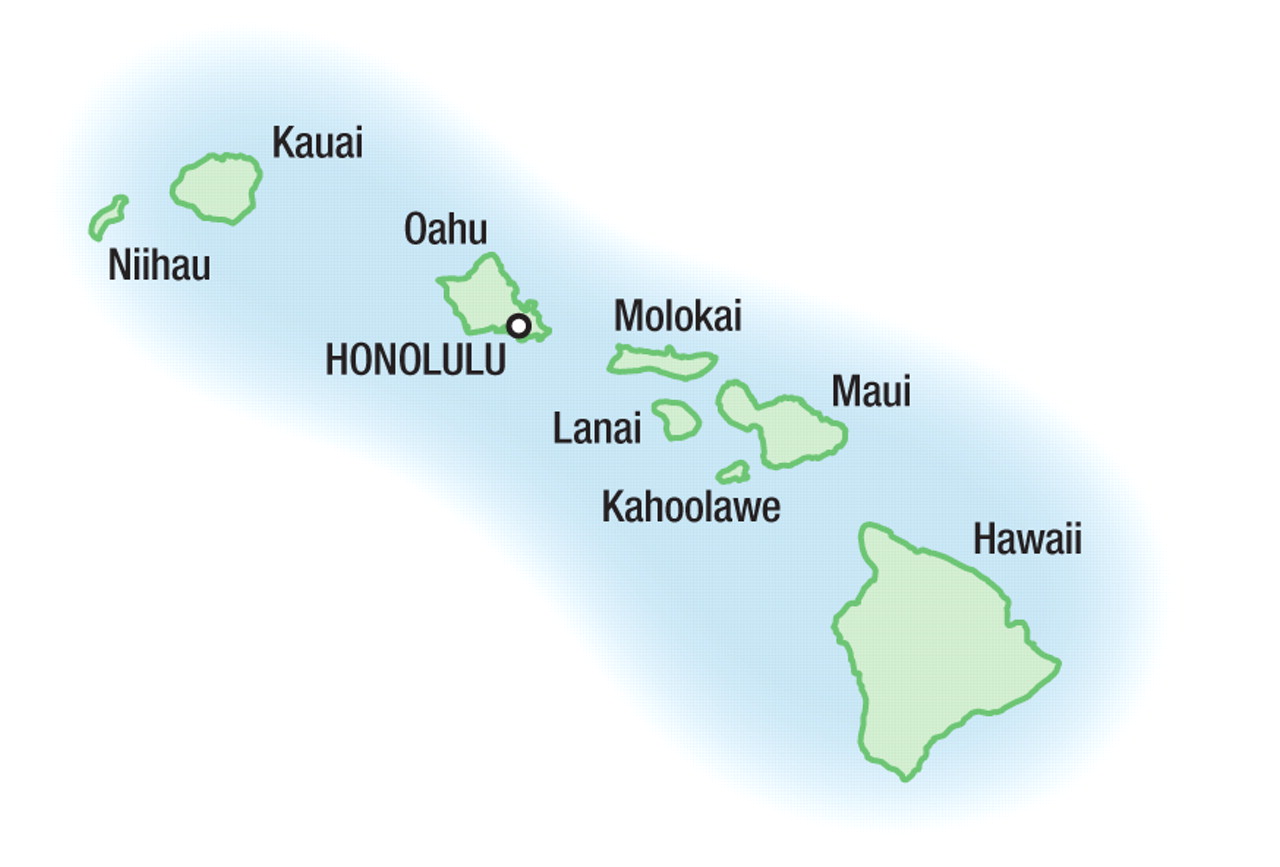

Koyanagi is working to expand the telepsychiatry network that reaches out to the “neighboring” islands—Molokai, Lanai, Maui, and Hawaii—plopped in the Pacific away from the Honolulu metropolis on Oahu.

“I think that telepsychiatry is an incredibly useful tool to provide care to underserved populations,” he said in an interview.

Take Molokai, for instance, a small isolated island, largely populated by Native Hawaiians. It illustrates the system's history and operation, said Koyanagi.

Until about 10 years ago, mental health care on the island was spotty. Clinicians came and went on a short-term basis, so the local people came to distrust outsiders who came to help. A statewide consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice mandated a comprehensive plan for delivering hospital and community-based mental health services in Hawaii and eventually led to creation of the telepsychiatry system.

Video Becomes Crucial Modality

Today, Koyanagi flies to Molokai once a month to see patients. He discusses cases with other mental health care clinicians, primary care doctors, probation officers, and others. Between visits he uses the video arrangement to stay in touch. He is always available by phone as well, including to staff of the emergency room at the Molokai hospital.

One or two psychiatry residents help him cover each remote site. “They're interested in getting the experience,” he said. “They see telepsychiatry as more prevalent in the future.”

At Hilo, the main city on the island of Hawaii, commonly called the Big Island, he adopts a more consultative approach, letting primary care providers manage most cases while he takes on the more difficult ones.

The local operation on Maui is based at a federally qualified healthy clinic (FQHC).

“Other FQHCs around the state are interested, but we want to do a few places well while we develop a sustainable model of care,” said Koyanagi.

Naleen Andrade, M.D., a professor and chair of the university's Department of Psychiatry, has begun research into how telepsychiatry affects community engagement and the role it can play in residency training. The university's medical school is one of the few in the United States that includes a telepsychiatry training component.

Another way to fill the rural gap is to practice in rural areas.

Gerald McKenna, M.D., grew up in a small town in upstate New York and, after detours through Boston and Los Angeles, now practices psychiatry on a small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Kauai, the northernmost island in Hawaii, covers 550 square miles and is home to approximately 50,000 people, served by about eight psychiatrists.

McKenna makes the case that Kauai is the most remote place on earth, if you measure the distance from the nearest continental land mass.

He first came to Kauai on a sailing trip with his son and returned in 1988 to stay. He has learned a lot since he arrived.

Hawaii is renowned for its beaches, surf, and volcanoes but also for a population as diverse as any in the United States. Native Hawaiians, Japanese, Filipinos, and Caucasians make up equal parts of the population, along with a smattering of other races and ethnic groups. Presentation of some psychiatric disorders often reflects these diverse cultural backgrounds.

Diverse Patients Require Understanding

McKenna specializes in addiction psychiatry and finds that an understanding of a patient's cultural background can help with treatment.

Hawaiians have their own approach to chemical-dependency treatment, called ho'oponopono, a cultural intervention derived from traditional ways of settling intra/interfamilial disputes. McKenna has adopted it to a degree in group therapy, in which the group has some say in what will work best in the treatment program.

He also integrates elements of Chinese medicine and acupuncture into his work, if desired by patients, for detoxification and relapse prevention, with the help of a physician of Chinese ancestry who has an office down the hall.

There are two psychiatrists in public practice on Kauai, treating mostly severely mentally ill patients. They use a nine-bed unit at Mahalona Hospital in Kapa'a for inpatients. Cases that cannot be handled there may be sent to hospitals in Honolulu, 37 minutes away by air.

“There is also good community support,” said McKenna. “People stay close to their families of origin, and there are large extended families.”

For example, when one new patient with methamphetamine psychosis came to his office recently, he prescribed medications to help the man detoxify, but put the patient's wife (who accompanied her husband) in charge of administering them.

“She'll do a good job, and when he's finished, he'll come back for outpatient treatment,” said McKenna.

Kauai's psychiatrists also provide consultations for their primary care colleagues.

“I feel like we're more a part of the general medical care system here than elsewhere,” he said.

Despite his choice of a remote practice location and relatively recent arrival, McKenna has taken major roles in the state's professional life. He is currently a delegate to the AMA and has served as president of both the Hawaii Psychiatric Medical Association and the Hawaii Medical Association.

He also lectures to residents at the University of Hawaii's School of Medicine about rural psychiatry issues and hosts a medical student in his office as part of a third-year rotation.