American news media provided mixed messages when reporting on the Food and Drug Administration's warnings about suicidality and antidepressant medication use for children.

Nearly all (98 percent) of network television and big-circulation newspaper stories accurately differentiated between suicidality and suicide, wrote Colleen Barry, Ph.D., and Susan Busch, Ph.D., of the Yale University School of Public Health in the January Pediatrics. However, other elements of the FDA warnings, like the need for close monitoring as patients began antidepressant treatment, were mentioned less than half of the time (43 percent).

Furthermore, there was a tendency to emphasize risks over benefits, they said. In stories that used anecdotes about individual children, 89 percent mentioned children who were harmed, but only 36 percent who were helped. (Some stories mentioned both classes of children.)

Stories that included interviews with physicians or other experts more often mentioned that benefits outweighed risks.

The FDA issued a series of five safety alerts in 2003 and 2004 about the possible association between antidepressant use and suicidality, the need for frequent face-to-face monitoring when starting drug therapy, and reminders to clinicians that only fluoxetine had proven effective in treating pediatric depression.

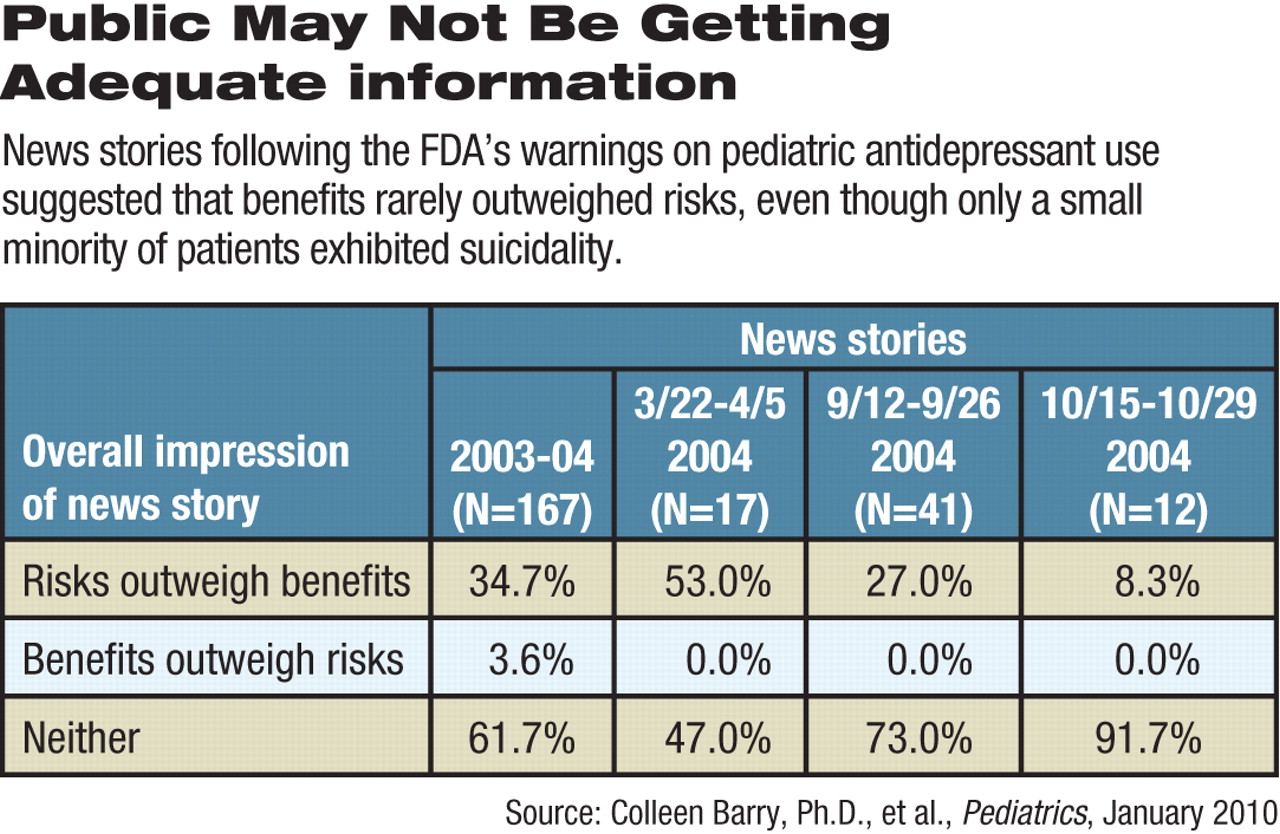

Overall, 62 percent of the stories delivered “neutral” overall impressions about the risks versus benefits of pediatric antidepressant use, the authors concluded. However, of the remainder, 35 percent said that risks outweighed benefits, while only 4 percent suggested the reverse.

By October 2004, following the last of the FDA's three alerts, 11 out of the 12 news reports recorded were rated as neutral on risks and benefits.

However, neutrality might be misleading, given that taking an antidepressant raised the absolute risk of suicidal thinking and behavior by only 1.4 percent compared with placebo. The FDA recommended closer monitoring of patients newly prescribed the drugs to manage any such suicidality. No patients in the trials the FDA reviewed committed suicide.

The emphasis on harm is not surprising, said Gary Schwitzer, an associate professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota and publisher of

HealthNewsReview.org, a Web site that evaluates news reporting on health.

“Reporters are looking for the ‘new,’ which in this case was the possibility of harms to patients,” said Schwitzer in an interview. “But we ought to expect stories to give good context on both harms and benefits in any coverage of tests, procedures, or medications.”

The finding that most of the stories gave an impression that the risks of antidepressants were greater than the benefits or vice versa may mean that viewers or readers are not getting enough information, said Schwitzer.

“Why discuss ‘impressions’ if you can let the data and the evidence speak for themselves,” he said. “Journalists should quantify the risks and benefits and let the readers decide.”

Telling Stories vs. Complex Findings

Barry and Busch gathered 167 reports in the United States from the 10 highest-circulation newspapers, the three major television networks, and CNN.

The research covered only major news outlets and not Internet news sources like the Web sites and blogs that have proliferated over the last decade.

They judged how closely the stories reflected the “key health messages” in the FDA warnings. They also looked at whether the stories mentioned a specific child who was helped or harmed by an antidepressant.

Television stories were more likely than print to make use of anecdotes and were also more likely to refer to a child who was harmed rather than helped by the drugs.

“News reporters often focus on the stories of individuals rather than on nuanced and complex findings,” said Benjamin Druss, M.D., M.P.H., the Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Some feared the warnings might lead to a reduced use of antidepressant medications for young patients. Different studies provided different estimates of the change in prescription rates, but the drop-off in use appropriately reflected the FDA's warning language, said Druss, the coauthor of a paper in the January 2008 Archives of General Psychiatry on the effects of the FDA warnings on antidepressant use.

“The new study confirms that the media did get some of these complicated and contrary findings across,” said Druss in an interview.

The Pediatrics article did not address whether reporters who filed the stories were specialists in science or medicine, who might have a better understanding of the context for the FDA's actions.

The recent upheaval in the journalism world is not likely to result in improved coverage, however. Science and medical journalists have taken many of the largest newsroom hits, and at least two highly regarded academic programs that trained health journalists were recently suspended. One (City University of New York) was stopped for lack of interest among students and another—Schwitzer's own department at the University of Minnesota—following state budgetary cuts.

The press will still have to play an intermediary role in relaying health information to the public, wrote Barry and Busch. “Simply including key health messages in FDA press releases was not sufficient to ensure that journalists mentioned this information in news stories.”

Or, as Druss said: “Any kind of public health effort is a relatively blunt instrument. The FDA sought to raise cautions, but may also have produced some unintended overreactions.”