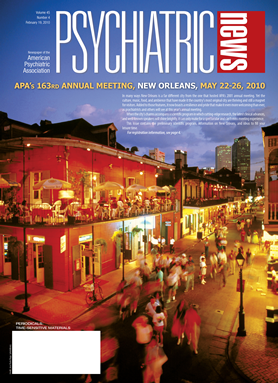

Mysteriously shadowed courtyards, lush, magenta bougainvillea draping wrought-iron balconies, jazz notes sallying forth from a saxophone into the sultry night air.

Welcome to New Orleans, a city hugging America's mightiest river, the Mississippi. And welcome specifically to New Orleans' historic heart—the French Quarter—which stretches along the Mississippi for several blocks.

New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville and was centered on the Vieux Carré, or old square. The Vieux Carré eventually became known as the French Quarter and is New Orleans' oldest neighborhood.

Three years later, the city-to-be was far from fetching. As one visitor described it, it was “a hundred wretched hovels in a malarious wet thicket of willows and dwarf palmettos, infested by serpents and alligators.” And during the next few years, it came to be settled by a volatile mix of officers, merchants, shopkeepers, smugglers, quasi-pirates, trappers, gold hunters, and riffraff.

In 1763 the Spanish gained control of New Orleans. After two massive fires, the wooden buildings constructed by the French were replaced with more fire-resistant ones made of brick or stucco and built adjacent to each other and close to the curb to create a firewall. The new buildings also had Spanish-style balconies or galleries made of elaborate wrought iron or cast iron, as well as Spanish-style courtyards in the back, containing flagstone paths, fountains, and magnolia and banana trees. One can easily imagine how pleasant it must have been to recline in one of those courtyards while a languorous breeze drifted in from the river.

In 1800, Spain gave Louisiana back to France. In 1803, the United States purchased it. Most new faces in New Orleans were now American—brawny boatmen and Yankee traders whom the French and Spanish residents disdained.

During the next few years, the city grew rapidly. There were influxes not just of Americans, but of Creole French (people of French descent born in the Americas), and even people from France. One of the new residents during the 1830s was a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte.

By 1840, the city was the fourth largest in the United States. The nearby Mississippi was congested with river boats, steamers, and ocean-sailing craft. At this juncture, the city had much of the wildness of a frontier town about it. But in 1849, New Orleans experienced a disastrous flood, the worst ever until that caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

The city's unique architecture mostly survived the American Civil War of 1861-1865 intact, but it was in 1905 that a major disaster hit in the form of a yellow-fever epidemic. President Teddy Roosevelt paid the city a visit against the advice of many who feared that he would contract the disease.

In 1934, simmering hatred between Louisiana Governor Huey Long and New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley came to a head. State troopers and armed city police faced off. Armed conflict was narrowly avoided.

In 1965, the French Quarter was designated a National Historic Landmark, and marking another landmark, in 1978 Ernest Morial became the first African-American mayor of New Orleans. Regarded as one of New Orleans' most accomplished politicians, he served two terms as mayor.

By 2000, the French Quarter still contained many of the buildings constructed under the Spanish or in the Spanish style. Although a number were used as hotels, bars, shops, or tourist attractions, others were private homes and occupied by people whose families had lived in the Quarter for generations. The temperament of the Quarter was still somewhat Gallic, the climate still alluringly sultry.

Because the Quarter is located on higher ground than much of New Orleans, it experienced far less damage by Hurricane Katrina's floods in 2005. So today, as in years gone by, it represents the heart of New Orleans for natives and visitors alike—impudent, raffish, yet at the same time, restrained and cultivated. Or as the French would say, “

Ah, c'est formidable!”