Children who are eventually diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) begin to show declines in social-communication skills after age 6 months, but early and persistent interventions may substantially improve their developmental outcomes, two recent studies demonstrated.

In a study published in the March Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, infants who were later diagnosed with ASD showed clear divergence in their developmental trajectory of social communication and engagement compared with healthy controls.

Researchers at the University of California (UC) Davis and University of California at Los Angeles, led by Sally Ozonoff, Ph.D., vice chair for research in the Department of Psychiatry at UC Davis, prospectively evaluated and followed two longitudinal cohorts of infants: a high-risk cohort who had older siblings with ASD and a low-risk cohort who had no ASD diagnosis in any first-, second-, or third-degree relatives.

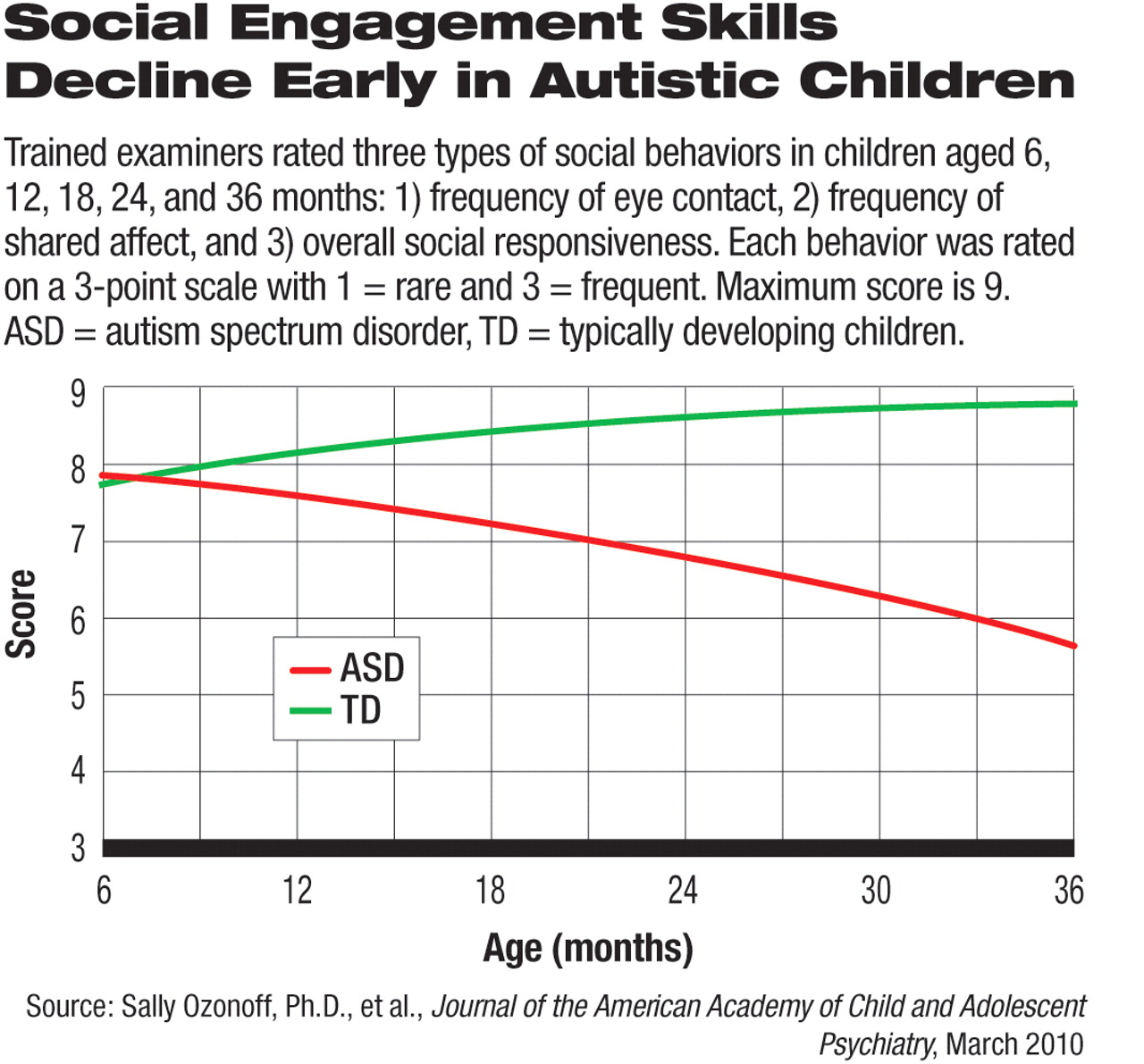

Each infant was directly assessed by a trained examiner at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months, and each assessment session was videotaped to allow researchers to measure precisely various aspects of the child's social-communication behaviors, including gaze to faces, social smiles (smiling while the child gazed at a face), and directed vocalization (vocalization while gazing at a face) during interactions with objects and another person. At the end of each session, the examiner, who was unaware of the child's risk for ASD, rated his or her impression of the child's frequency of eye contract, frequency of shared affect, and overall social responsiveness.

Among these studied infants, 25 met the diagnosis of ASD at age 36 months, including 22 from the high-risk cohort and three from the low-risk cohort. They were compared with 25 infants without ASD at 36 months who had been randomly selected from the low-risk cohort.

Declines Continued

The 25 children who were later diagnosed with ASD showed normal development in social-communication behaviors at the six-month visit that was indistinguishable from that of children who did not develop ASD. However, at the 12-month visit, they differed significantly from the healthy children in measurements of gaze to faces and directed vocalization. All aspects of social assessments, including both the researchers video-based measurements and the examiners' impression-based rating scores, showed further decline at the 18- and 24-month visits for the ASD patients (see chart).

The researchers also found that the parents' retrospective reports of ASD-symptom onset, collected at 36 months, were very different from the prospective assessments, which suggested that the gradual decline was difficult for parents to detect. It was particularly notable since most parents in this study had an older child with ASD and were expected to be more aware of early signs of autism.

“Our most widely used and recommended practice for gathering information about symptom onset—parent-provided developmental history—does not provide a valid assessment of the slow decline in social communication,” the researchers concluded. Rather, they suggested that clinicians' prospective screenings of a child's social behaviors in the period from ages 6 months to 24 months may be important for picking up signs of deterioration as early as possible.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Intensive Interventions Improve Outcome

In another randomized, controlled study, 48 children between 18 months and 30 months of age and diagnosed with ASD or pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) were assigned to either a treatment program known as Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) or usual community care. After two years, children who underwent ESDM intervention showed greater improvement in intellectual development and adaptive behavior compared with children who received usual care.

The ESDM was developed by Geraldine Dawson, Ph.D., at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Salley Rogers, Ph.D., at UC Davis; they were also coauthors of the study. Children in the ESDM group underwent an average of 15 hours a week of intensive interventions with a trained therapist for two years and 16 hours a week of ESDM-guided interactive activities with parents who were taught by the study staff. Children in the usual-care group received an average of nine hours a week of individual therapy and nine hours of group interventions such as special-education preschool.

After two years, the children's scores on the Mullens Scales of Early Learning increased by 17.6 points in the ESDM group and 7.0 points in the usual-care group. The difference was statistically significant.

The ESDM group also showed significantly higher Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale scores, which measured social, communication, motor, and daily living skills based on parents' reports.

However, the two groups of children did not differ significantly in the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule severity score and repetitive-behavior score at two years.

This study was supported by an NIMH grant and published in the January Pediatrics.