A group of academic medical centers in Massachusetts is confronting the familiar shortage of child psychiatrists with a program that combines telephone consultations, outpatient evaluation, care coordination, and continuing medical education.

Pediatricians are well-attuned to children's mental states and behaviors, thanks to their understanding of child development. However, modest training in psychiatry limits their ability to manage mental health problems in their young patients.

Beginning five years ago, the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP) expanded mental health services for the state's children by offering pediatric primary care clinicians quick consultation and closer collaboration with child psychiatrists and other mental health specialists.

The MCPAP grew out of a pilot study at the University of Massachusetts (Psychiatric News, August 5, 2005) that now extends throughout the state.

“We wanted to create a collaborative model of care, where the pediatrician manages most care with the help of child psychiatrists but can refer a patient when needed,” explained Barry Sarvet, M.D., an associate clinical professor at Tufts University School of Medicine and vice chair of psychiatry at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. Centers affiliated with the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Harvard Medical School also took part in the program.

“We think of child psychiatry not as standing alone but serving as a subspecialty of pediatrics,” said Sarvet in an interview.

The MCPAP laid the groundwork for the program with a series of visits by the participating child psychiatrists to primary care practices serving children and adolescents. Clinicians in these practices included family practice physicians and nurse practitioners, as well as pediatricians. Practices signed a formal enrollment document laying out obligations and expectations for both sides.

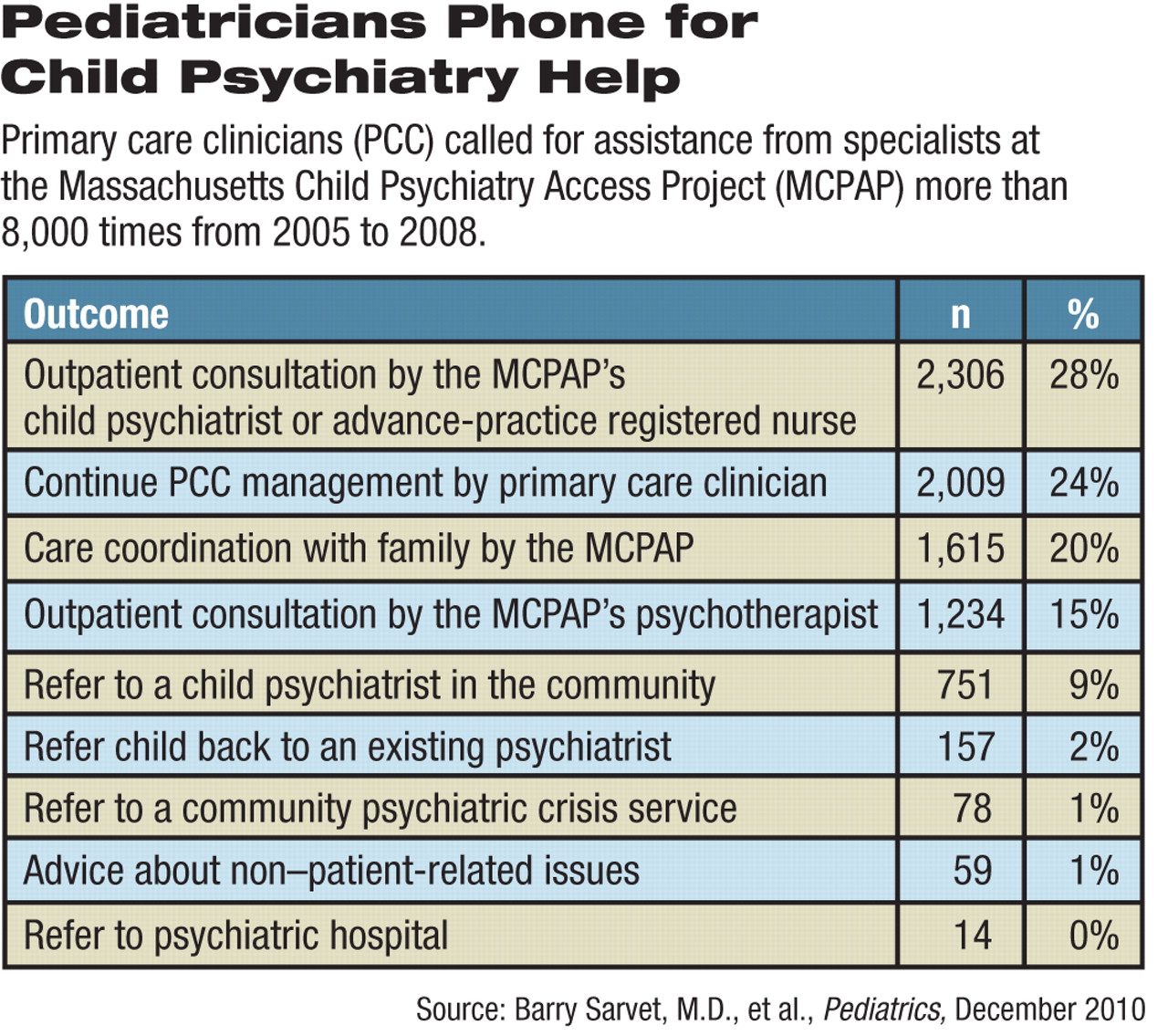

The MCPAP now covers nearly all practices and children in the state. The program signed up 353 practices including 1,341 primary practitioners from 2005 to 2008, the period covered in a report on the system published by Sarvet and others in the December 2010 Pediatrics. There were 33,335 patient encounters logged during that time.

Each regional medical center in the program set up a team consisting of one fulltime equivalent (FTE) child psychiatrist, an FTE child and family psychotherapist, and an FTE care coordinator. The child-psychiatry slot is actually shared by three to five individuals at each medical center. During their time on duty, they schedule “interruptible” tasks that they can leave quickly when a pediatrician calls, said Sarvet.

When a primary care clinician calls the care coordinator, the latter identifies the caller's needs. Not all calls require a psychiatrist's response. Some involve finding community mental health services for patients.

If the caller does need help with a diagnosis or medication consultation, the care coordinator alerts the psychiatrist.

“We agree to call back within an hour at the latest, but in the majority of cases, the call is returned in 15 or 20 minutes,” said Sarvet.

Calls to the MCPAP coordinator from 2005 to 2008 asked for diagnostic assistance (34 percent), identification of community resources (27 percent), and medication information (27 percent). The most common diagnoses in the children seen were attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (32 percent), depression (24 percent), and anxiety (23 percent).

If the patient needs a more intensive evaluation than can be managed over the phone, an MCPAP clinician schedules a face-to-face outpatient visit with a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the nearest affiliated medical center, usually within two weeks. The psychiatrist provides written assessments and recommendations to the primary care clinicians within 48 hours of seeing the patient.

Ordinarily, the MCPAP team members do not provide continuing care, although the psychotherapist may step in and do some therapy if waiting times for community resources are considered excessive.

“Part of the orientation involves explaining that this is not like the usual referral process,” said Sarvet. “With MCPAP, the primary care provider holds on to more responsibility.”

Continuing education for the primary care clinicians is woven into the MCPAP process. Regional conferences are scheduled, but each consultation also functions as a case-based seminar that provides recent research, practice guidelines, and assessment suggestions to the primary care clinician.

Peter Kenny, M.D., M.P.H., a pediatrician in private practice in Northampton, Mass., finds two advantages to the program.

“I've become more knowledgeable and more confident about treating patients with psychiatric diagnoses,” he said in an interview. “Then there's the matter of medical liability.”

When the FDA added black-box warnings to some antidepressant labels, many primary care physicians worried about prescribing such drugs to young patients, he explained. Some withheld needed medications. Consulting with child psychiatry experts alleviates that concern, he noted.

Asked if he had any suggestions for improving MCPAP, Kenny replied, “Yes, they could work right here in our office.”

That level of collaboration is not likely to happen soon, but the connections forged in the process may lead the way to better provision of care to young people.

“This model is a way not only of providing services to patients but to transform the entire field so that all child psychiatrists are regularly talking with pediatricians and sharing the care with them,” said Sarvet.