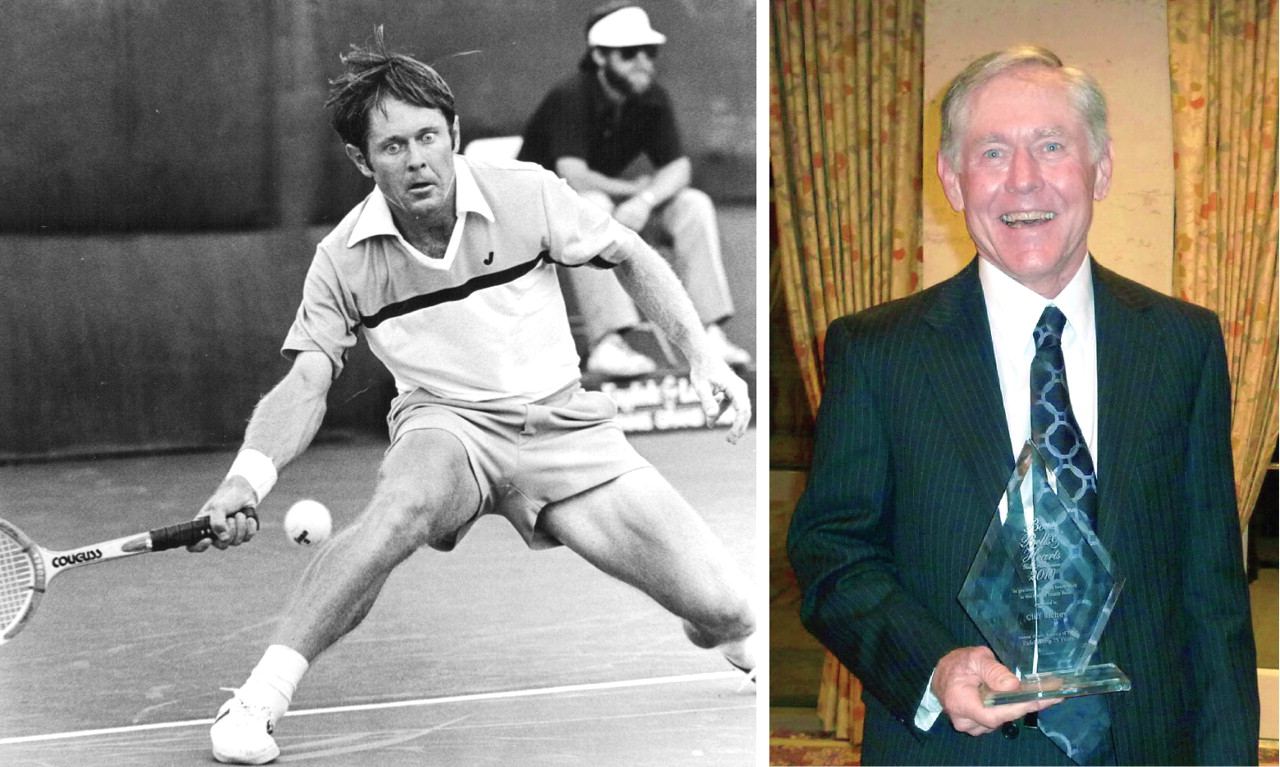

A former U.S. tennis champion and original “bad boy” of tennis has emerged the victor in one of the toughest matches of his life and with one of his most formidable opponents—depression.

Cliff Richey is now educating others that diagnosis and treatment can be lifesaving.

Richey was born on New Year's Eve in 1946 in San Angelo, Texas. His father was a professional tennis player and instructor who taught Richey and his older sister, Nancy, to play the game at a very young age. Richey played tennis through the 1970s and then as a “senior” during the 1980s.

As pre-teens, the Richey siblings were already winning tournaments around their home state and soon would play and win on the national and international stage.

Life inside “Richey Inc.,” as Richey now refers to his tennis-winning family in his autobiography Acing Depression: A Tennis Champion's Toughest Match, was a pressure cooker. Winning was all important to the family. While their peers were going on dates, the Richey siblings sacrificed social lives and concentrated on improving their tennis skills.

By the late 1960s, Nancy had reached the semifinals at Wimbledon and won the French Open, and Richey had won his first professional match against Rod “the rocket” Laver at Madison Square Garden in New York.

Poised for a Fall

The following year would be a banner year for Richey—at age 23, he was playing in the semifinals of the French and U.S. Open matches and won eight tournaments.

In October 1970, Richey played and won a “sudden death” match (a match in which there is a nine-point tiebreaker) against Stan Smith, placing Richey in the coveted role as the top-ranked tennis player in the United States. But that year he also endured the most difficult loss of his career in the semifinals of the French Open to Zeljko Franulovic.

Even when Richey was on a winning streak, he would ask his father and coach why happiness eluded him much of the time. “Don't those trophies mean anything to you?” the elder Richey would ask his son, pointing at the wall where they stood.

Richey would reply, “No. They mock me.”

However, in Acing Depression, which he co-authored with his daughter, Hilaire Richey Kallendorf, Ph.D., years after achieving celebrity, Richey likened the morale-boosting effect of his victories to that of an antidepressant on a depressed person and admitted to using tennis as a “salve” for the emotional pain he was experiencing. His marriage also suffered from his rigorous schedule, the constant pressure of competition, and the disappointment of high-stakes losses on the court.

At least a decade before John McEnroe burst into temper tantrums on court, Richey was berating linesmen for what he considered to be erroneous calls and had the dubious distinction of being known as the “original bad boy of tennis” after McEnroe rose to fame. Once he threatened an opponent, Clark Graebner, with his tennis racket during a match in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla.

He didn't realize it at the time, but he was suffering from depression, he told Psychiatric News. The depression worsened in the following years, with Richey losing himself in a relentless schedule of games. “I felt out of sync with everything and everyone,” he wrote.

Winning the Ultimate Match

The losses became more frequent for Richey through the next couple of decades, as his depression took its toll.

His depression hit a crescendo in the mid-1990s, when he began to feel hopeless, took no pleasure in anything, and succumbed to ever-present emotional pain. He rarely left the house, was unable to sleep, and taped black trash bags in the windows of his west Texas home to block all sunlight.

Richey visited his dermatologist to have some cancerous lesions removed from his skin in 1996. His dermatologist suspected that he was clinically depressed and recommended that Richey start antidepressant medications, which he did, without hesitation.

An internist who was a family friend took over Richey's care and prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor that Richey has taken ever since.

Once he went public with his diagnosis, he received resounding support from friends, family, and longtime tennis colleagues. In fact, five-time U.S. Open champion Jimmy Connors wrote the foreword to Richey's book and urged him to “keep fighting.”

Richey attributes his recovery not only to antidepressant medications, but also to his love of golf, which he had begun playing regularly in the 1980s after sustaining an injury that made it difficult for him to play tennis on a competitive basis.

Richey also said that his role as a mental health advocate is an essential part of his recovery from mental illness. When New Chapter Press published his book in April, Richey traversed the country, combining tennis clinics with talks and book signings, and has lectured to a variety of audiences about his struggles with depression and subsequent treatment.

He finds audiences' responses “heart-warming” and told Psychiatric News that he has helped more than a few people seek treatment for depression.

Occasionally, Richey experiences set-backs with depressive episodes—milder than they once were—and he is able to combat them through a variety of techniques that he shares with audiences, he said.

These include something Richey calls “defaulting the day” in which he accepts that things may not be going his way for one reason or another, and he decides not to feel stressed about it. He also reverts to a “grey zone,” or middle ground, in which, for example, he can accept that for one day, he is not playing golf as well as he normally does.

He also finds it helpful to focus on the positives in his life, which are many—a long and successful career in tennis, three adult children, close friends, and a new life as a mental health advocate. “I have been blessed beyond anything I could have ever imagined,” he remarked.