Most antisocial individuals are emotionally volatile and impulsive. However, a minority are emotionally cold, superficially charming, manipulative, and lacking in empathy and remorse—that is, they possess certain personality traits often linked with psychopathy.

A new study suggests that the brains of individuals who are antisocial and have psychopathic personality traits differ from the brains of those who are antisocial and who do not have such traits. The study was led by Nigel Blackwood, M.D., a senior lecturer in forensic psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. The results were published online May 7 in the Archives of General Psychiatry.

Blackwood and his colleagues attempted to recruit violent offenders from the United Kingdom’s National Probation Service for their study. Forty-four of the offenders who expressed interest in participating in the study were found to meet DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder and had no lifetime history of major mental disorders and no substance use disorders during the prior month. The 44 were then evaluated with the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, which measures psychopathic personality traits.

Seventeen subjects were found to have the psychopathic syndrome (that is, scored above 25 on the checklist), and 27 did not have the syndrome. The 44 subjects were compared with 22 healthy nonoffenders who served as controls.

The researchers then used structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualize and measure the brain volumes of the three groups of subjects.

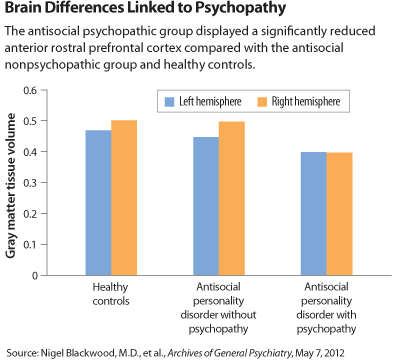

They found no significant brain differences between the antisocial-without-psychopathy group and the healthy controls, which surprised them, they acknowledged in their paper. But they did find significant differences between the antisocial-with-psychopathy group and the other two groups.

The antisocial-with-psychopathy group had significantly reduced gray-matter volume in the anterior rostral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 10) and the temporal cortex (Brodmann area 20/38).

“These [brain] regions are central to the development of self-conscious emotions, such as guilt or embarrassment, which promote pro-social behavior and form the basis of moral learning,” the researchers pointed out. “Both regions are routinely activated in moral-reasoning tasks and in the recognition of moral violations. Based on this evidence, the structural volume decrements observed in these regions among the offenders with antisocial personality disorder plus psychopathy may contribute to the profound social impairments that characterize psychopathy.”

Yet if such deficits contribute to psychopathy, why do they exist in the first place? The researchers provocatively suggested that “psychopathy is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by structural abnormalities from a young age.” They conceded, however, that a prospective investigation with repeated brain scans would be required to test this hypothesis. Blackwood told Psychiatric News that he will be conducting such an investigation.

Commenting on the study, Paul Appelbaum, M.D., the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University, chair of the APA Committee on Judicial Action, and a past APA president, told Psychiatric News, “Structural brain imaging may ultimately improve our understanding of antisocial behavior and psychopathy, but it is important not to overinterpret the results of a single study.”

“Although this study found structural differences in the psychopathic group, the samples were small, and the data failed to confirm many of the findings of previous studies,” Appelbaum said. “The ease of coming up with posthoc explanations for just about any differences found underscores the importance of generating and testing clear hypotheses regarding affected brain areas. Finally, we have to keep in mind that structural differences, even if real, do not necessarily imply functional changes. This study should be seen as generating hypotheses for future confirmation, not as a definitive statement of how the brains of psychopaths are different.”

The study was funded by the U.K. Department of Health, U.K. Ministry of Justice, U.K. Psychiatry Research Trust, U.K. National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Center, and the Institute of Psychiatry.