Heart attacks are bad enough for the patient but sometimes they can take a serious toll on the patient’s spouse as well, reported researchers from Denmark and the United States in the European Heart Journal published online August 21.

They emphasized that “clinical attention needs to be paid to both the patient, who is suffering from the physical and mental trauma of the event, and the spouse, who has to live through the event alongside the patient,” said Emil Fosbøl, M.D., Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C., and the Gentofte University Hospital in Hellerup, Denmark.

“[L]osing a spouse or having a spouse experiencing a nonfatal AMI [acute myocardial infarction] is a major public-health issue for which there is very little awareness among physicians and policymakers,” the researchers wrote.

Fosbøl and colleagues examined Danish National Health Service records for four groups of spouses (about 77 percent were women) for up to a year.

Spouses of individuals who died of a fatal AMI totaled 16,506 and were compared with spouses of 49,518 people who died of other causes. Researchers also compared 44,566 spouses of nonfatal AMI patients with spouses of 131,564 patients with nonfatal, non-AMI hospitalization.

They looked at patterns of antidepressant and benzodiazepine use in the spouses of all four groups.

Spouses whose partners eventually died of a heart attack used fewer antidepressants before the AMI, but were prescribed them three times more frequently after the event. Usage peaked at two months after the event and declined by one year after. Spouses of those who died of causes other than AMI had increased rates of antidepressant use, but not as great as the spouses in the fatal-AMI group.

There was a slight increase in benzodiazepine and antidepressant use in the nonfatal AMI spouse group, but none in the nonfatal, non-AMI spouse cohort.

Benzodiazepine use rose sharply among spouses in the fatal AMI group a month after the event, less so in the fatal non-AMI group and in the nonfatal AMI group. Little change in use of these medications was observed in the nonfatal, non-AMI group. However, few spouses were still using the benzodiazepines a year after the event.

There was a significant increase in depression diagnoses among the surviving spouses of both groups of fatalities, with husbands exhibiting a greater risk of incident depression than the surviving wives.

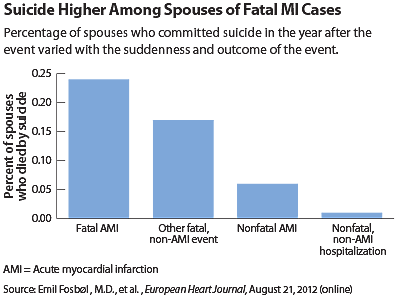

Suicide rates were low, but spouses of those who died were significantly more likely to take their own lives than were those whose partners had nonfatal illnesses.

The differences among spouses in all the outcomes assessed in the study may be due to the fact that death by AMI is frequently sudden and unexpected, suggested Fosbøl and colleagues.

“This acute loss appears to have a larger psychological impact on the spouse than a loss due to other causes—in line with theoretical considerations comparing bereavement with posttraumatic stress disorder,” they said.

The implications for these events extend beyond the losses and anxieties of individual families.

About 7 million AMIs occur each year worldwide, leading to an estimated 46,000 additional prescriptions for anti-depressants and perhaps 1,400 suicides among spouses, said Fosbøl. “[O]ur study suggests that losing a spouse or having a spouse experiencing a nonfatal AMI is a major public health issue for which there is very little awareness among physicians and policymakers.”

The study was supported by an award from the American Heart Association-Pharmaceutical Roundtable and David and Stevie Spina.