One of the most common beliefs about rates of psychiatric symptoms that arise after disasters is that things are worse after manmade tragedies than after natural disasters.

But that may not be the case, according to a leading researcher.

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was “not independently associated with disaster type” after controlling for “preexisting characteristics of the exposed populations and the specifics of their exposure,” wrote Carol North, M.D., M.P.E.; Anand Pandya, M.D.; and Julianne Oliver in the October American Journal of Public Health.

North is a professor in the departments of Psychiatry and Surgery/Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and director of the trauma and disaster program at the VA North Texas Health Care System.

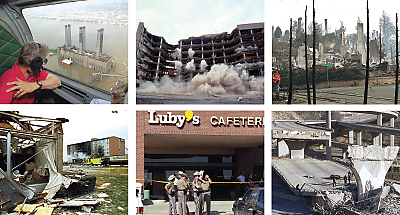

She and her colleagues used standardized data-collection methods to interview 811 survivors of 10 disasters that occurred from October 1987 to April 1995. All events occurred in the United States and included a flood, a tornado, an earthquake, a firestorm, a plane crash, four shootings, and the Oklahoma City terrorist bombing.

North made full diagnostic assessments using structured diagnostic interviews conducted one to six months after the event. That uniformity made it possible to combine data and analyze them across disasters.

This rigorous approach means the researchers could do an “apples-to-apples” comparison of the effects of different disasters, said Ann Norwood, M.D., a senior associate at the Center for Biosecurity at UPMC in Baltimore, who was not involved in the study.

Nearly all (94 percent) of the survivors were directly exposed to these events, with 39 percent being injured and 40 percent witnessing injury or death. Despite those exposures, most people surveyed did not incur a psychiatric diagnosis.

After the disaster, though, 20 percent did meet criteria for PTSD, 16 percent did so for major depression, and 9 percent for alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol use disorder had a lifetime prevalence of 23 percent prior to the disaster, but measurements of predisaster alcohol disorders represent lifetime rates, while the postdisaster figure reflects postdisaster prevalence, North told Psychiatric News.

“The disaster did not cause widespread sudden sobriety, just as it did not abruptly cause widespread new alcohol disorders,” she pointed out.

Several Predictors Identified

After adjusting for demographic or event-related factors, the researchers found that predictors of PTSD included female gender, younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, less education, ever-married status, predisaster psychopathology, injury, and witnessing death or injury. This pattern generally confirmed much prior research.

Data on PTSD symptoms, however, were not so conventional. Overall, many people in the sample met criteria for Group B reexperiencing/intrusion symptoms (71 percent) or for Group D hyperarousal symptoms (68 percent). But only 24 percent met criteria for Group C avoidance and numbing symptoms, said the researchers. However, 84 percent of the third group also met criteria for full PTSD, opening up its potential as a quick, one-shot indicator of future psychiatric problems.

“[G]roup C emerged as a marker for PTSD,” they said. “If Group C can predict PTSD in the first days after a disaster, then people with high risk for developing PTSD could potentially be identified well before the full month that is required before a diagnosis can be considered.”

Disaster Type Didn’t Play Role

In addition, multivariate analysis controlling for exposure and preexisting conditions eliminated any association of PTSD with disaster type—man-made versus natural.

North and her colleagues have not used precisely the same methodology since 1995, she said.

“But we did a 9/11 study that was quite similar, the major difference being that the data collection did not begin until well into the third postdisaster year, due to logistical reasons related to research funding, permissions, and access to samples,” she said. Findings from that study are under review for publication.

Wider use of the same protocols by other researchers might expand the body of comparable data, said Norwood.

“There have been attempts to get investigators to standardize their approaches, but most prefer to use their own favorite tools,” said Norwood. “Maybe new researchers entering the field will try to be more consistent.”

North’s methods have not been widely applied because they consume much time and money, even as researchers are faced with “diminished funding for additional descriptive disaster studies…. [and] methodological trends to obtain larger samples and enter the field sooner,” she said.

Funding for the study came from the National Institute of Mental Health.