The “number of accurate portrayals of psychiatry or psychoanalysis in the history of U.S. film can be counted on one hand,” said Glen Gabbard, M.D., a psychoanalyst and a clinical professor of psychiatry at the Menninger Clinic at Baylor University College of Medicine and co-author of the book Psychiatry and the Cinema.

Safe to say, “A Dangerous Method” won’t require a second hand. The new film by director David Cronenberg, based on scriptwriter Christopher Hampton’s own play and “drawn from true-life events,” tells the fictionalized story of the ambiguous six-year relationship between Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung and the patient who ties them together.

The patient is Sabina Spielrein, portrayed by Keira Knightley with much thrashing about and thrusting of jaw.

The title method in question is Freud’s, as Jung, played by Michael Fassbender, tells his patient: “Talk. Just talk.”

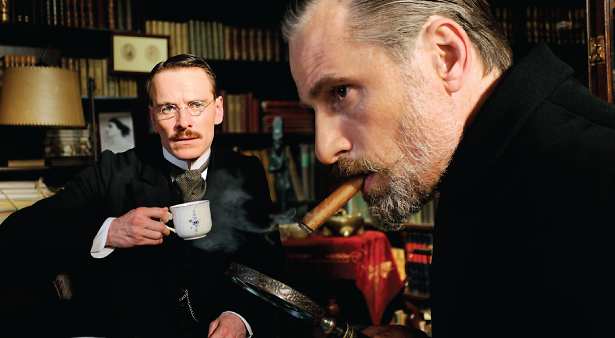

In 1907, Jung writes to Freud (played by actor Viggo Mortensen) about a new patient, diagnosed with hysteria, and then goes to visit the older man in Vienna to discuss psychoanalysis.

Almost immediately, the foreshadowing of disagreement appears in this first, 13-hour-long conversation between the two. Freud suggests that Spielrein is “fixated in an anal state” and therefore obviously “finicky, stubborn, and stingy.”

Oh no, says Jung, she is actually “masochistic, disorganized, and emotionally generous.”

It won’t be their only disagreement.

Back in Zurich, mere talk between Spielrein and Jung doesn’t last long.

She reveals to Jung that her father’s spankings when she was little excited her sexually. She gives him a kiss and points out her apartment building in case he misses the hint.

This gets a nonplussed Jung thinking, a process nudged along by another patient, Otto Gross (portrayed by Vincent Cassel), a real-life psychoanalyst with a drug problem who was sent by his father to Jung for treatment. If Gross did not invent the boundary violation, he appears to have perfected it, having slept with patients and called it therapy.

“Never repress anything,” he tells Jung, who gets the message. And sure enough, Jung and Spielrein soon aren’t repressing much when alone together in her apartment.

Now, no one knows if the real Jung and the real Spielrein had real sex together, said Gabbard, but their kinky activities in the movie make the filmmaker’s views clear.

Spielrein recovers from her mental illness almost too quickly, attends medical school in Zurich, becomes a psychiatrist, and starts coming up with her own ideas about life, sex, and death, which eventually impress both the psychoanalysts.

“How did she recover so rapidly to write major, intelligent papers?” wondered Gabbard. “You would not expect that from someone with true psychosis.”

Eventually, Jung suggests that professional resistance to psychoanalysis is due to Freud’s insistence on sexualizing human behavior. Freud waves him off: “All I’ve done is open the door.”

By 1913, the final breach occurs as the two exchange frosty farewells based on actual letters, the film indicates.

Ultimately, we see Jung formulating the ideas about archetypes and the collective unconscious that will gain him adherents around the world.

“What [Freud] will never accept is that what we understand will get us nowhere,” Jung tells Spielrein. “We have to go into uncharted territory. We have to go back to the sources of everything we believe. We must set the patient on a journey at the end of which is the person he was always intended to be.”

“A Dangerous Method” is beautifully filmed and intellectually engaging, but for a film about transgressive sex and breaking cultural taboos, it remains curiously emotionless and distant from the viewer. Perhaps that is a reflection of psychoanalysts’ obligation to maintain a distance from their patients.

But then, films are films, said Gabbard. “Cinematic psychotherapy has a whole set of principles that are different from real-life psychotherapy, because films have to entertain an audience,” he said.

“I suspect that both Jungians and Freudians will be disappointed,” said Gabbard.