The cost of treating Medicaid patients for depression has risen in recent years, despite a decrease in the use of inpatient and outpatient mental health services and an increase in the availability of generic versions of many antidepressant medications.

These findings come from a study published in the December 2011 Archives of General Psychiatry that examined trends in spending and quality of care for 56,805 Florida Medicaid enrollees diagnosed with depression between July 1, 1996, and June 30, 2006.

For the study, Catherine Fullerton, M.D., M.P.H., of Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance led a team from Harvard Medical School’s departments of Psychiatry and Health Care Policy in pooling data on individuals aged 18 to 64 who were either hospitalized for depression or had at least two outpatient claims for depression during the 10-year study period.

While the percentage of patients hospitalized for depression dropped from 9.1 percent to 5.1 percent over the study period, and the percentage of individuals receiving psychotherapy declined from 56.6 percent to 37.5 percent, the use of antidepressants increased from 80.6 percent to 86.8 percent and the use of antipsychotics jumped from 25.9 percent to 41.9 percent.

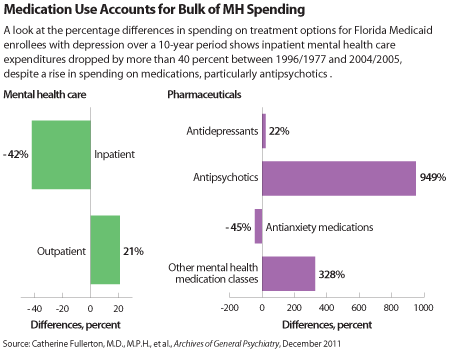

The researchers noted that the increased use of psychotropic medications was associated with a 110 percent rise in spending per patient throughout the study’s 10 years, including a 949 percent increase in antipsychotic expenditures and a 328 percent increase in the amount of money spent on classes of psychotropics other than antidepressants and antianxiety agents (see chart).

By the end of the study period, Medicaid enrollees with depression were costing a mean of $3,610 per year in mental health services, up 29 percent from $2,802 at the outset of the study. These figures are adjusted for inflation.

In light of the increased spending on antipsychotic medications, the researchers recommended that guidelines be developed and cost analyses conducted on the use of these drugs in treating individuals with depression.

To assess the quality of care for individuals receiving treatment during the acute phase of depression, the researchers considered patients’ adherence to prescribed medication regimens, access to psychotherapy, and number of follow-up visits with a mental health care clinician.

The study found an increase from 65.1 percent to 75.2 percent in the number of acute-phase episodes of depression for which psychotropic medications were prescribed. But while the percentage of patients receiving “minimally adequate drug treatment” (defined as filling an anti-depressant prescription for 75 percent of the days in treatment) rose from 58.7 percent to 68.2 percent during the course of the study, the percentage receiving three or more follow-up visits dropped from 19.4 percent to 10.9 percent.

Additionally, the percentage of acute-phase episodes in which patients received psychotherapy dropped from 42.6 percent to 26.9 percent.

Among patients hospitalized for acute depression, the percentage of episodes in which antidepressants were prescribed remained relatively constant, while the percentage of episodes involving psychotherapy dropped from 32.3 percent to 18.6 percent.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations to their study, including a focus on only patients receiving a diagnosis of depression, a lack of information on patient outcomes, and treatment practices that may have changed in the past five years with the introduction of new medication options.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health.