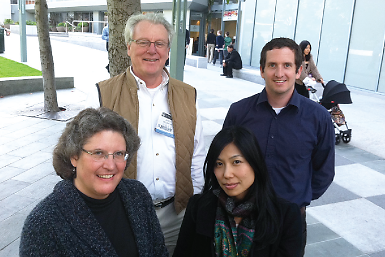

Fumi Mitsuishi, M.D., and Ryan Shackelford, M.D., are pioneers of sorts.

They are the first holders of the University of California, San Francisco’s (UCSF) fellowship in public psychiatry, a program that kicked off just last July as “the only active public-psychiatry fellowship in the state of California,” according to codirector James Dilley, M.D., vice chair of psychiatry at UCSF and chief of psychiatry at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH).

The first two fellows are both former chief residents, Mitsuishi at UCSF/SFGH and Shackelford at the University of California, San Diego’s combined family medicine/psychiatry residency program.

Mitsuishi said that taking part in a start-up should give her more flexibility and teach her more about the process of creating programs in the future.

“There was little teaching in my residency about quality or ‘systems-based’ practices,” she said in an interview with Psychiatric News.

The UCSF fellows work 80 percent of their time in a community health service and spend 20 percent in a program of seminars and research to learn more about the practice of public psychiatry.

Mitsuishi accepted a placement in a San Francisco clinic visited mainly by Cantonese-speaking patients. Working there teaches her about the important role of culture in medical care and how she can work with translators and case workers to better help her patients, she noted.

She takes a midweek break from clinical work, returning to UCSF for didactic sessions. “That gives me a chance to go back and forth between the micro and macro perspectives on medical care,” she said.

Shackelford is spending his fellowship in San Francisco County’s South of Market mental health clinic, working with a largely homeless and chronically mentally ill population. As part of his fellowship, he is performing a quality improvement study on ways that primary care services can be better brought to the seriously mentally ill patients there.

“I’m studying patient records to see who is getting only psychiatric care, who is getting only general medical care, and who is getting both,” he said. “The results will help the clinic improve the referral process and suggest how to better allocate resources.”

The one-year fellowship is directed by Dilley and Christine Mangurian, M.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at UCSF.

The fellowship’s didactics cover eight areas, mostly dealing with systems issues:

The role of the psychiatrist in publicly funded community services

The structure of public-psychiatry systems

Homelessness and housing policy

Recovery and psychosocial rehabilitation

Integration of psychiatric and primary care

Management and budgeting skills

Advocacy at the state level

“Training as a clinician is different from training as a manager,” Dilley told Psychiatric News. “The overall mental health system needs people who understand both clinical care and management.”

Funding for the fellowship comes through San Francisco County’s grant from California’s Mental Health Services Act as part of a workforce development program. The two-year grant covers stipends for the fellows and parts of some faculty salaries, plus a research assistant’s time to help with data entry. Fellows get a salary, benefits, and an appointment as clinical instructors in UCSF’s Department of Psychiatry at SFGH.

Fellowships in public psychiatry have had an erratic history, said Jules Ranz, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center and director of the Public Psychiatry Fellowship at the Columbia-affiliated New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Ranz uses a broad definition of “public” psychiatry, seeing it as encompassing not just work for government-run entities, but also employment in other, usually nonprofit, organizations whose funding sources are ultimately tax supported.

About a dozen public-psychiatry fellowships appeared in the 1960s after passage of the 1963 Community Mental Health Act, but none lasted, probably because there was no steady funding source, Ranz said in an interview.

Many of those fellowships closed in the 1970s, but some small ones—more like mentorships—began early in the 1980s, he noted.

If UCSF is a brand-new baby, then Columbia is the grandfather of public-psychiatry fellowships. Columbia’s began in 1981, supported by stable funding from the state of New York. At least 15 other fellowships were created in the last 10 years.

At least four current fellowship programs—at New York University, Case Western Reserve, UCSF, and the University of Texas Southwestern—were started by alumni of the Columbia program, Ranz pointed out. UCSF’s Mangurian went through the Columbia program.

For the fellows at UCSF, the program eases the shift from traineeship to the next stage of their careers.

“You’re working almost as much as a full-time job, but you’re not quite out on your own,” said Shackelford.

The core of a public-psychiatry fellowship is leadership training, and the strategy for learning leadership is experience as a participant-observer, said Ranz.

“The best way to understand a system is to be active in that system, take on a role, and try to create some change, especially change above the level of the individual doctor-patient relationship,” he said.

“It’s not just another year of training,” said Ranz. “It’s the first year of their career.”