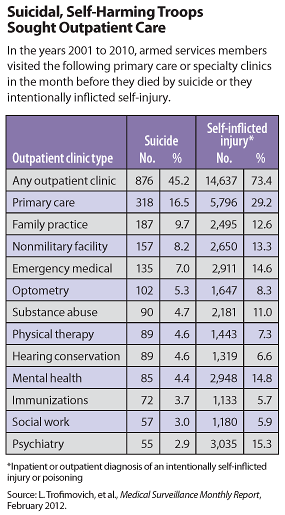

About 45 percent of military service members who died by suicide visited outpatient medical clinics in the 30 days prior to their deaths, according to Department of Defense researchers.

Even higher percentages of cases of self-inflicted injury (73 percent) or likely self-harm (76 percent) sought medical care in the month before the event, according to a team from the National Center for Telehealth and Technology of the Defense Center of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury in Tacoma, Wash.

“The study reminds us to be aware of the risk of suicide even when the focus of the visit is not a mental health issue,” said coauthor Mark Reger, Ph.D., in an interview with Psychiatric News. “The problem is that the risk of suicide for any one case is so low that it is a challenge for clinicians to spot it.”

These clinic visits may signal “a final call for help by individuals who have made specific plans to end their lives,” wrote Reger and colleagues in the February Military Surveillance Monthly Report, a publication of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center.

The study looked at the death and medical records of all active-duty service members from the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines from 2001 through 2010. Over that time, 1,939 service members died by suicide, 19,955 were diagnosed with self-inflicted injuries, and 3,463 were hospitalized with injuries or poisoning classified as “likely self-harm.”

Only 7.3 percent of the individuals who later died by suicide visited a mental health or psychiatric clinic in the month prior to suicide, but 26.2 percent showed up in family or primary care offices. Seven percent percent appeared in substance abuse clinics.

About 8.2 percent sought medical care in nonmilitary health care facilities, despite having full military health insurance.

Those who died by suicide made excessive clinic visits to nonmilitary facilities and to family practice, substance abuse, and emergency medical settings, said Reger and colleagues.

However, greater proportions of the self-inflicted injury cases and the likely self-harm cases visited mental health or psychiatry clinics than suicide cases did.

Among all three classifications, the most frequent primary diagnoses made by nonmilitary facilities were musculoskeletal disorders, “signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions,” injuries, and mental disorders, said the researchers.

Overall, the three cohorts used health care in ways similar to their unaffected peers until shortly before their deaths or injuries.

“The finding suggests that there may be one or more ‘triggering’ events during which thoughts of self-harm intensify and lead to increased health care usage in many clinical settings,” they said. “Distressed service members may seek health care services in the hope that clinicians might recognize or help ameliorate the distress.”

Better training of primary care practitioners or easier access to mental health clinicians might improve detection of suicidal intentions, said Mark Kaplan, M.D., a professor of community health at Oregon’s Portland State University who studies suicide for the Department of Veterans Affairs.

That is especially critical in military cohorts, said Kaplan in an interview with Psychiatric News, since about 70 percent of Army soldiers who die by suicide, die of gunshot wounds. So the first attempt at suicide is often the final attempt, given the lethality of firearms.

“The opportunity to intervene and rescue an individual who is suicidal and who has access to a gun is fairly limited,” said Kaplan.

Unfortunately, while 45 percent of suicide decedents appeared in a clinic before they died, the majority had no such contact, leaving no opportunity for intervention, noted Reger and colleagues.

A separate study by some of the same researchers and other colleagues in the same publication, found that “mood disorders, partner relationships, and family-circumstance problems, but not mild TBI [traumatic brain injury], were associated with increased odds of suicidality.”

They suggested that looking at constellations of these symptoms and diagnoses may offer clinicians better clues to suicidality.