Reports on the effectiveness of selected clinic-based multimodal day treatment programs are summarized, followed by an overview of reports on the efficacy of laboratory-based preventive, child-oriented, parent training and classroom-based interventions.

Effectiveness of clinic-based multimodal day treatment programs

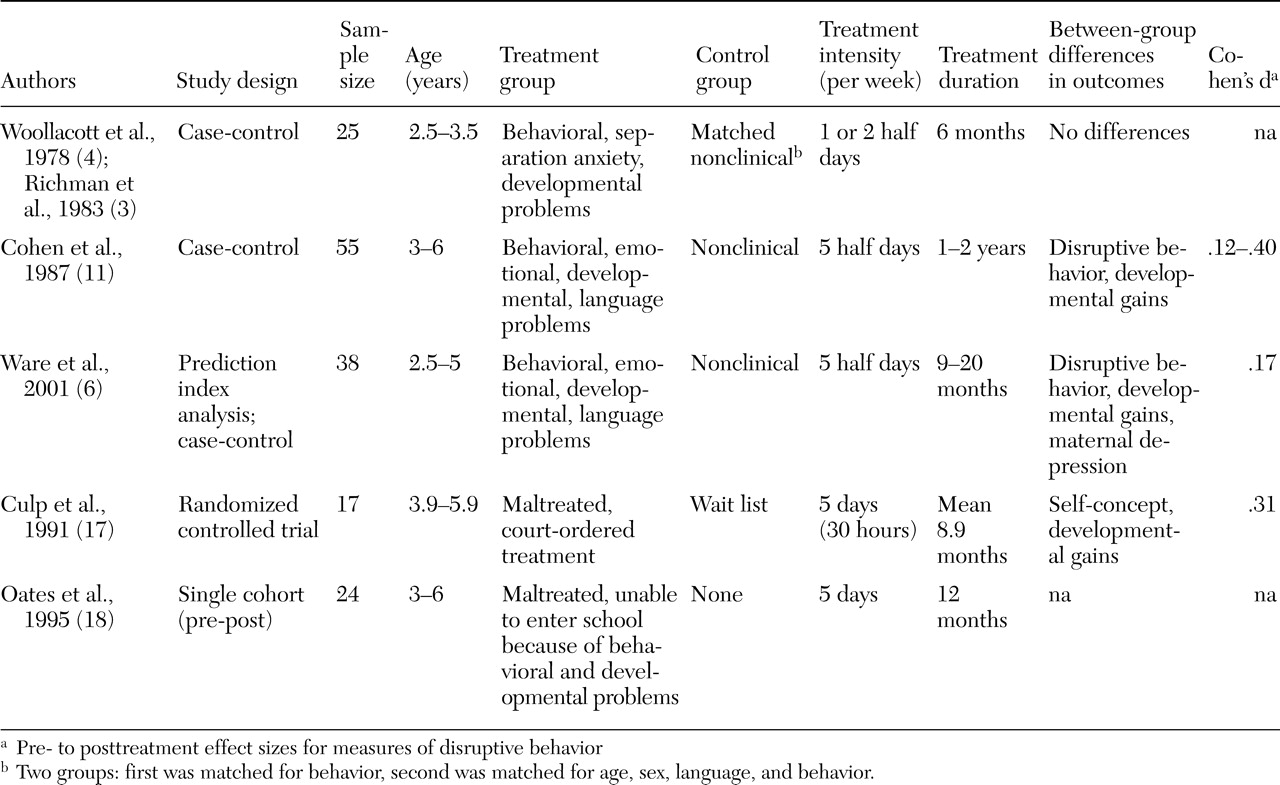

Only five studies of preschool day treatment programs were found that reported quantitative outcomes, for a combined total of 159 children. Study characteristics are summarized in

Table 1 .

In one of the earliest studies of day treatment, Woollacott and colleagues (

4 ) described children referred to a therapeutic nursery that emphasized parent-oriented interventions. Mothers interacted with their children in the nursery, where the focus was on parental attunement and mother-child communication. A mothers' support group and social work liaison were also offered. The treatment group made no more gains than matched children in the nonclinical control group at one- and five-year follow-up (

3,

4 ).

Cohen and colleagues (

11 ) reported on a prescriptive multifocused treatment program for preschoolers. A variety of interventions were employed, according to the treatment goals of each child. These could include setting limits, helping the child to verbalize feelings, and implementing speech therapy, among other things. Families were expected to observe and work with their children in the playroom and were seen regularly by a social worker. Behavior changes were found only among children who remained in the program more than one year. Children who had both behavioral problems and developmental delays made more gains than children without developmental delays. Family motivation was correlated with goal attainment. Little change was found for the nonclinical control group.

Ware and colleagues (

6 ) reported on a psychodynamically oriented program involving special education, individual and group play therapy, and weekly family therapy. On measures of daily living skills—socialization and visual-motor integration with established age-based norms—significant gains in developmental level were found, compared with gains that could be predicted on the basis of change in the child's age. Other uncontrolled pre- to posttreatment gains in behavior and parental functioning were found. On follow-up in first and third grade, graduates of the program needed less special education than children with similar problems identified in kindergarten (an unmatched comparison group).

Two of the programs described in the literature search were developed to address behavioral and emotional problems among children who had been physically or sexually abused. In one program, maltreated preschoolers received a specialized curriculum emphasizing feelings and relationships (

17 ). The preschoolers also received individual play therapy, speech therapy, and physical therapy. Their parents received intensive services, including family therapy, education, and a 24-hour crisis line. A randomized controlled study found increased peer acceptance and developmental gains for children who received this program. In this study use of a wait list control group was justified, because participation in the program was mandated by judicial order, but space in the program was limited.

The second program provided maltreated preschoolers with a curriculum emphasizing limit setting and consistency, along with individual psychotherapy (

18 ). Parents were supported through regular home visits. The success of the program was determined by school entrance after a year of treatment. Developmental gains were also reported, but no comparison group was available.

These day treatment studies offered a range of interventions, with children in each study receiving different interventions. Few specifications were given for diagnoses of children in these studies. Different outcome measures and methods of comparison were used. Therefore, it is difficult to derive meaningful conclusions about the effectiveness of day treatment programs by examining these reports. It is not possible to know whether the one negative study did not find between-group differences because the intervention was ineffective or because the control group was poorly matched. Only one study employed a truly comparable (randomized) control group.

On a very general level, it is possible to conclude that modest evidence shows that multimodal day treatment programs can be effective. Treatment tends to result in developmental gains. One commonality of the programs described was that they all expected families to be involved. Only one study made any suggestion about the effect of duration of treatment or type of child problem on effectiveness (

11 ). No information on the effect of treatment intensity could be found, and no comparisons were made with conventional outpatient treatment. It appears that the research base for this costly and intensive model of service delivery is lacking.

Efficacy of laboratory-based interventions

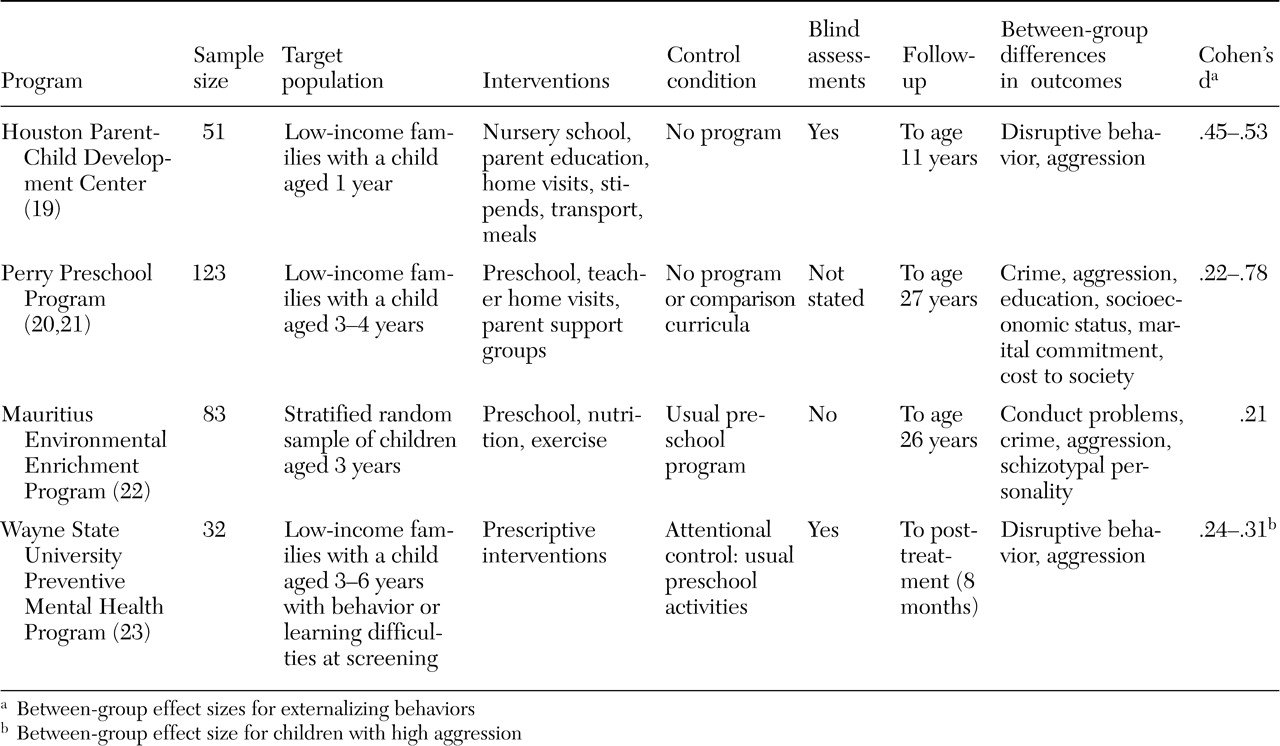

Efficacy of multimodal prevention programs. Four randomized controlled trials of multimodal prevention programs for preschoolers were found. These programs recruited low-income families, based on findings that socioeconomic status is associated with antisocial characteristics. The studies are summarized in

Table 2 .

The Houston Parent-Child Development Center offered a two-year program involving home visitation, parent training, preschool education, and family workshops (

19 ). A broad range of other resources were available, including stipends, meals, and transportation. Positive child behavioral and family socioeconomic outcomes were found on follow-up up to eight years later.

The Perry Preschool Program also combined high-quality child education with home visitation. Parent support groups were offered as well. Decreased delinquency and improved academic and employment outcomes were found up to age 27 for individuals who had attended the Perry Preschool Program. Costs from crime were reduced by about $70,000 per child (

20,

21 ).

These primary prevention strategies were exported to Mauritius in the Environmental Enrichment Program, where preschoolers were randomly selected to receive a two-year program of nutrition, education, and exercise (

22 ). Many of these children were malnourished upon entry to the program. Lower rates of antisocial behavior and schizotypy were found up to 26 years of age for individuals who went through the preschool program.

Wayne State University's Preventive Mental Health Program employed a prescriptive approach, similar to the prescriptive multifocused treatment offered in the clinic-based day treatment study of Cohen and colleagues (

11 ). In this prevention program, preschoolers found on screening to have learning and behavioral difficulties were randomly assigned to receive either customized behavioral interventions or "placebo attention" in addition to their regular preschool program (

23 ). Between-group differences were found in behavior and academic functioning at the end of the eight-month program.

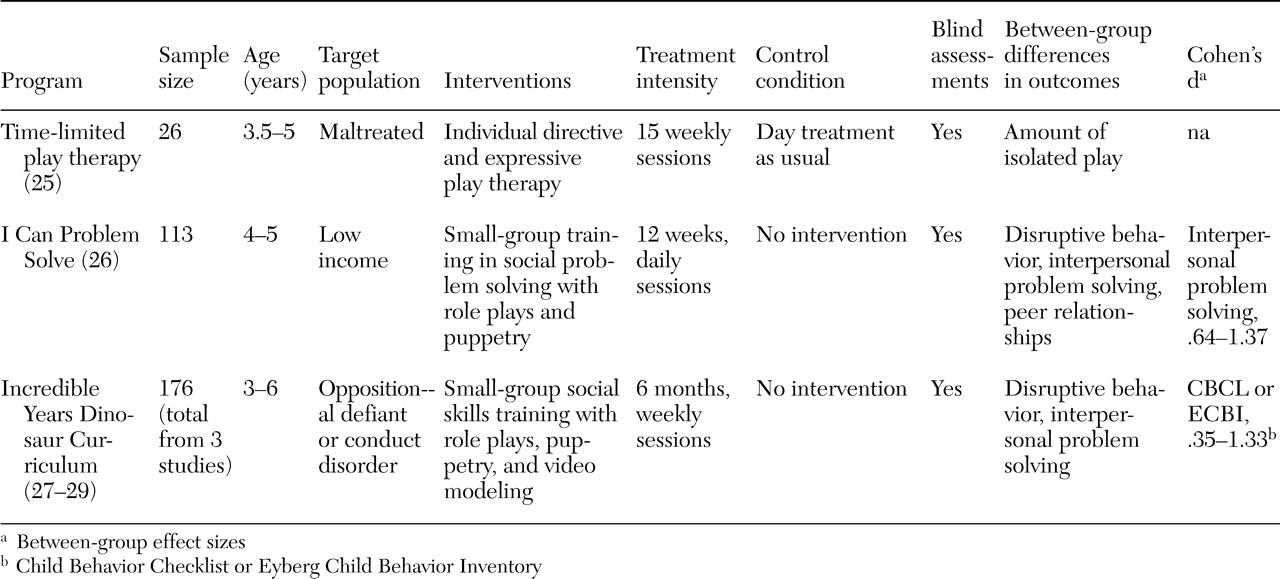

Efficacy of child-oriented interventions. Several training programs focusing on social, anger-management, and problem-solving skills have been developed for children, but only two had been tested in randomized controlled trials with preschool-aged children: I Can Problem Solve and the Incredible Years Dinosaur Curriculum. These programs target aberrant social cognition, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of conduct disorder (

24 ). Only one randomized controlled study of child psychodynamic therapy was found (

25 ). This study found no significant effects on behavioral measures when individual play therapy was added to a day treatment program. These three studies are summarized in

Table 3 .

I Can Problem Solve is a three-month small-group program teaching preschoolers interpersonal problem-solving skills and emotional literacy, using puppetry and role-play games to promote learning (

26 ). Improved classroom behavior, peer relationships, and interpersonal problem solving were found for preschoolers who received the program as a preventive intervention. Positive outcomes were maintained at follow-up in grade five to six.

The Dinosaur Curriculum adapts the principles guiding I Can Problem Solve to treat children referred with conduct problems. Children meet in small groups for two hours each week for 22 weeks. The multimedia sessions employing videos and life-size puppets emphasize emotional literacy, empathy, friendship skills, anger management, interpersonal problem solving, and school success. Three randomized controlled trials showed decreases in peer aggression and noncompliant behavior and increased prosocial and problem-solving skills among children who received the curriculum (

27,

28,

29 ).

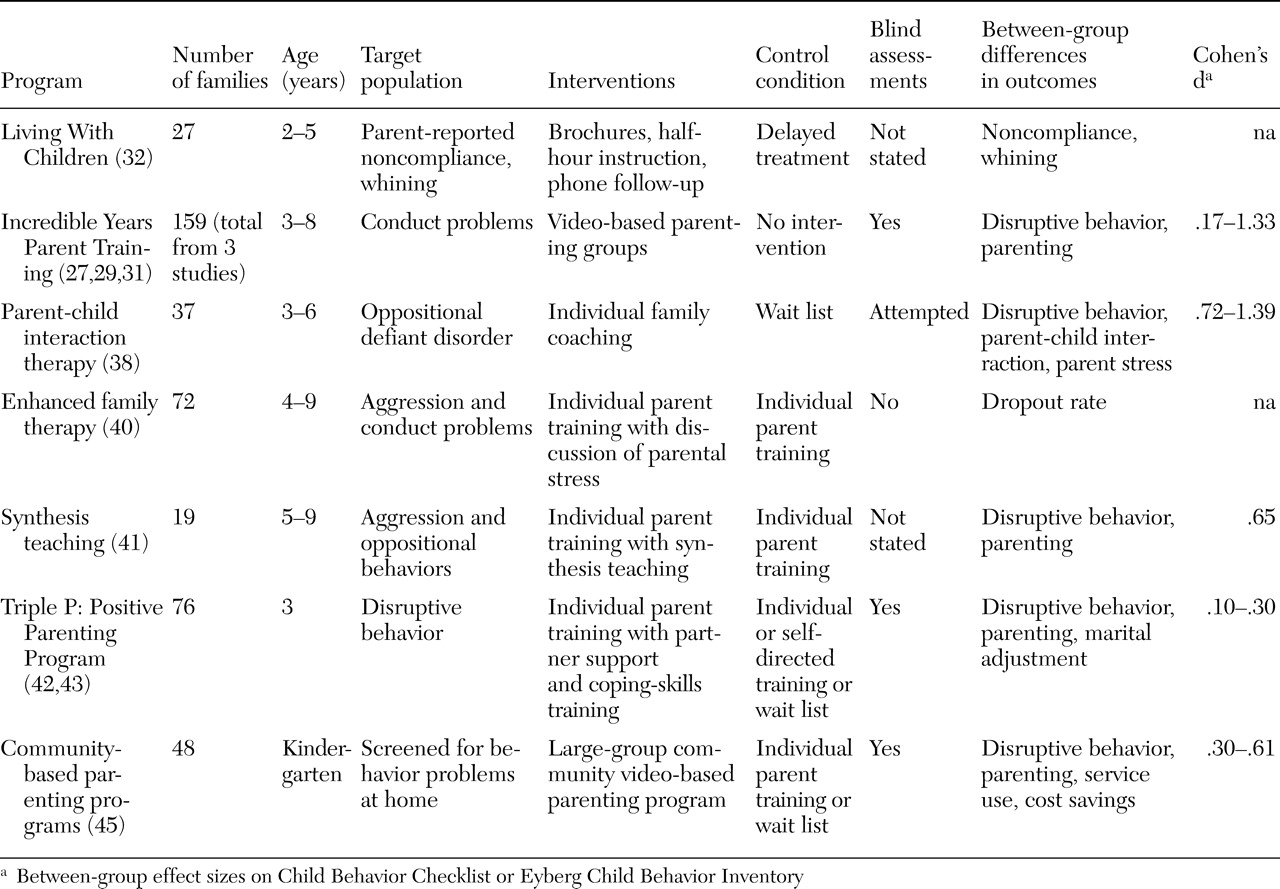

Efficacy of parent training interventions. Parent training has been robustly supported in the literature on treatments for disruptive behavior disorders. Several parent training programs have been tested in randomized controlled trials that include preschool-aged children. These trials are summarized in

Table 4 . They are organized here to highlight aspects that may inform clinical family-oriented services.

Brestan and Eyberg (

30 ) deemed only two treatment programs to be "well established" in their review of 82 studies of psychosocial treatments for children. One was the Living With Children manual, and the other was the Incredible Years videotape modeling parent training program (

27,

29,

31,

32 ). Both programs teach parents to monitor and reward positive behaviors and to ignore and give consequences for deviant behaviors. Timeouts are an important part of both programs; this behavioral technique has been found to be essential in a randomized controlled trial (

33 ). Parental self-control and self-talk techniques are emphasized in the Incredible Years program. Living With Children is designed for the training of individual families but has been adapted for group training (

34 ), whereas the Incredible Years program is designed for groups but can be self-administered (

35 ).

The content of most parent training programs is similar, rooted in social learning principles, but several studies have suggested that program format and delivery may have an effect on training effectiveness. For example, families that were randomly assigned to receive the Incredible Years videotape modeling parent training in a self-administered format had more difficulties at the three-year follow-up than families who received the training with therapist-led group discussion after each videotaped vignette (

31,

35 ). Families randomly assigned to receive only the therapist-led discussion did not fare as well as the group that received both the videotape modeling parent training and therapist-led discussion. Of note, studies of the Incredible Years parenting program tend to have dropout rates of less than 10 percent, whereas dropout among families referred to parent management programs is usually in the range of 50 to 75 percent (

36,

37 ).

Another program enhanced by technology is parent-child interaction therapy, in which therapists coach parents through a "bug-in-the-ear" earphone from behind a one-way mirror. Parent-child interaction therapy has been extensively tested, with findings that clinically significant behavior changes in treated preschoolers are maintained up to six years later (

38,

39 ). However, no studies comparing parent-child interaction therapy with other therapies were found.

Enhancing the content of programs for parents may also influence their engagement in therapy. Lower dropout rates were found for families that were randomly assigned to a standard (social-learning-based) family therapy enhanced by therapists' solicitation of parents' feelings and concerns, compared with families that received the family therapy alone (

40 ).

Synthesis teaching, in which parents are trained to discriminate child care stresses from stress from other sources and to examine similarities between the ways that they respond to their child and to other people, was more efficacious than unenhanced parent training in improving parenting and child behavior (

41 ).

Studies of the Triple P: Positive Parenting Program found that a marital communication skills program (partner support training) added to a parent training program enhanced treatment gains for families with marital discord (

42 ). However, differences in outcome were limited when all families were included, and no difference was found in dropout rates (

43 ). Webster-Stratton (

44 ) also found that, although skills training in marital communication enhanced parental functioning, it did not improve child behavior outcomes. The Triple P research group concluded that there may be limited benefit in offering targeted interventions for parental distress to all referred families.

Practical factors have also been implicated in parent engagement in therapy. Location may be an important factor for some families: those whose first language was not English and who had children with more severe problems were more likely to participate in a community-based parenting program if it was held in a school rather than in a medical center (

45 ). Financial compensation, flexible scheduling, and reminder letters have also been used to increase parental compliance (

38 ).

Efficacy of classroom-based interventions. As shown in

Table 5, two classroom-based programs were found that had been tested in randomized controlled trials that included preschool-aged children. The Contingencies for Learning Academic and Social Skills program (CLASS) has been adapted for kindergarten-age children (

46 ). This intervention involves awarding points to a disruptive child for on-task behavior. Essentially, CLASS manualizes the social-learning principles of monitoring, contingent attention, and reinforcement for use in a classroom setting. In the First Step to Success program, CLASS increased on-task behavior among children identified with behavior problems.

The Incredible Years Teacher Training program also facilitates teachers' integration of social-learning principles into classrooms. Teachers attend workshops that last four to six days and offer a video-based curriculum on classroom management skills and relationship building with students and their parents. Improved classroom behavior was found for children whose teachers received training (

29 ).