The burden of disease attributable to depression is formidable: depression is becoming the major source of disability, second only to cardiovascular diseases; it is the main source of disability in the Canadian workplace (

1 ) and the U.S. workplace (

2 ). However, recent population surveys in both countries have shown that a majority of affected people did not receive treatment in the 12 months before being interviewed (

3,

4,

5 ). Factors associated with unmet need for treatment in the United States have included age, race and ethnicity, type of insurance coverage, and income, as well as rural residence (

5,

6 ). Similarly, in Canada factors that were associated with unmet need for treatment included older individuals, low levels of education, and rural residence (

7 ).

In both countries deinstitutionalization in the past years has changed the delivery of mental health services. Now a majority of services are delivered on an outpatient basis in general hospitals and nursing homes and by primary care clinicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and psychotherapists.

Given the changes seen in the mental health delivery system, a more recent study considering mental health service use in both countries is of interest. Such international comparisons may elucidate health system factors related to access and availability of mental health services, which can contribute evidence to inform and improve mental health policy making. Further, describing each country's use of the mental health care system can serve to inform future comparisons, which may elucidate whether countries that implement and follow their national mental health policies see improvements and a more efficient allocation of services.

Methods

Data

The JCUSH is a nationally representative telephone survey that was administered in 2003 in Canada and the United States (

16 ). The study populations, persons aged 18 years and older who live in noninstitutional dwellings, were contacted by using random-digit dialing. The sampling design aimed to produce nationally representative data for both Canada and the United States, and age-standardized weights were produced (

18 ). In total, 3,505 of 5,311 Canadians and 5,183 of 10,366 Americans responded to the survey. The survey was administered in both countries by Statistics Canada by using the computer-assisted telephone interview method, the same questionnaire, and the same interviewing team. The questionnaire was designed by both countries and administered in French and English for Canadian interviews and in English and Spanish for U.S. interviews. The content of the JCUSH was based on existing questions found in both countries' separate ongoing health surveys: the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) and the National Population Health Survey in Canada and the National Health Interview Survey in the United States. Measures of quality assurance included using highly skilled interviewers and training interviewers with respect to survey procedures and the questionnaire. More details on the survey content and methods used are presented elsewhere (

16 ).

Past-year health service use for mental health reasons

Service use in the past 12 months for mental health reasons was ascertained as follows: "In the past 12 months, have you seen or talked on the telephone to a health professional about your emotional or mental health?" Information on type of health professional consulted was also ascertained. Mental health service use was studied according to the following combinations: any type of health professional, a general practitioner or family doctor, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and another professional provider (for example, nurse, social worker, or counselor). Past-year use of primary care providers was also examined as three combinations of service use: general practitioner or family doctor only, general practitioner or family doctor and at least one other health professional, and any health professional except for a general practitioner or family doctor.

Explanatory variables

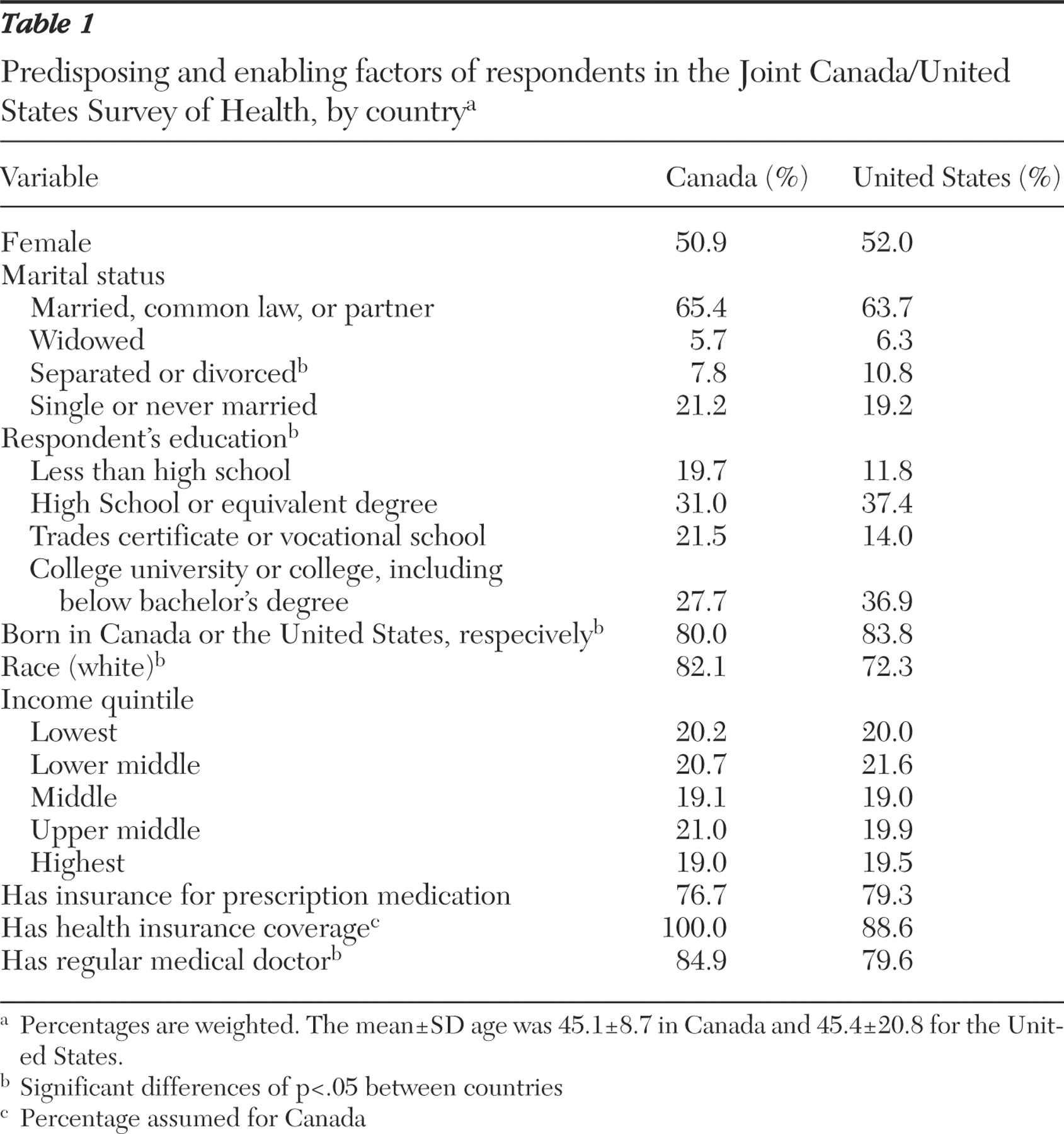

Mental health service use was studied as a function of depression, as well as a function of other factors found in the survey. Predisposing factors of interest were age, sex, marital status, education, country of birth (Canada or United States versus abroad), and racial origin (white versus other). Enabling or impeding factors studied were household income adjusted for household size (quintiles), insurance coverage for prescription medication, having a regular medical doctor, and current health insurance coverage (for the United States sample only; the study assumed that all Canadians had basic health insurance).

In this study depression was represented as the likelihood of a major depressive episode based on responses to a subset of items from the World Health Organization's (WHO's) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The scores obtained from these questions were coded for

DSM-III-R and transformed into a probability estimate of a diagnosis of a major depressive episode. The presence of depression was based on the probability (<.90) that the respondent would have been diagnosed as having a major depressive episode in the past year if he or she had completed the full version of the CIDI. The measure of depression was based on the short form of the CIDI (CIDI-SF) used by WHO for epidemiologic and cross-cultural surveys, and its value has been supported in comparison to the longer form (

19 ). Other studies have also validated the reliability of using the CIDI-SF to diagnose depression (

20,

21 ), as well as the relevance of using predictive diagnostic instruments such as the CIDI-SF in telephone surveys and large-scale health surveys (

22 ).

Other need factors studied included perceived unmet emotional or mental health need, perceived general health, emotional problems, presence of a chronic medical condition, and the impact of long-term physical conditions, mental conditions, and health problems on the principal domains of life—that is, whether and to what extent the amount or the kind of activity is reduced. Disability was derived from five questions about vocational restriction of activities. If the respondent positively endorsed any one of the five items, they were considered to have a disability. Questions were the following: Because of a physical, mental, or emotional problem, do you need the help of other persons with personal care, do you need help in handling routine needs, were you kept from working, were you limited in the kind or amount of work, and were you limited in any way in any activities?

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to model any type of mental health service use, as well as by provider type, as a function of country, depression and other predictors, and correlates of service use (predisposing, enabling or impeding, and need factors). Country-specific differences with respect to determinants of mental health service use were also studied. In order to account for the different health care systems in the two countries, a variable with three categories was created and included in all analyses as dummy variables, Canada (reference), United States with medical insurance, and United States without medical insurance. The following interactions were tested between the three categories—Canada (reference), United States with medical insurance, United States without medical insurance—and sex, country of birth, race, depression, unmet mental health need, perceived general health, emotional problems, presence of a chronic condition, and disability.

Multivariate analysis of depression was also studied as a function of health care system (Canada versus the United States with medical insurance and the United States without medical insurance) and potential confounders (age, sex, marital status, education, income, country of birth, race, prescription insurance, and regular medical doctor).

Estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed by using the Bootvar program developed by Statistics Canada (

23 ). All estimates presented are weighted and account for the effect of the sampling design. One thousand bootstrap weights were used to calculate the 95% CI. The data were analyzed by using the SAS statistical software version 9.1.

Discussion

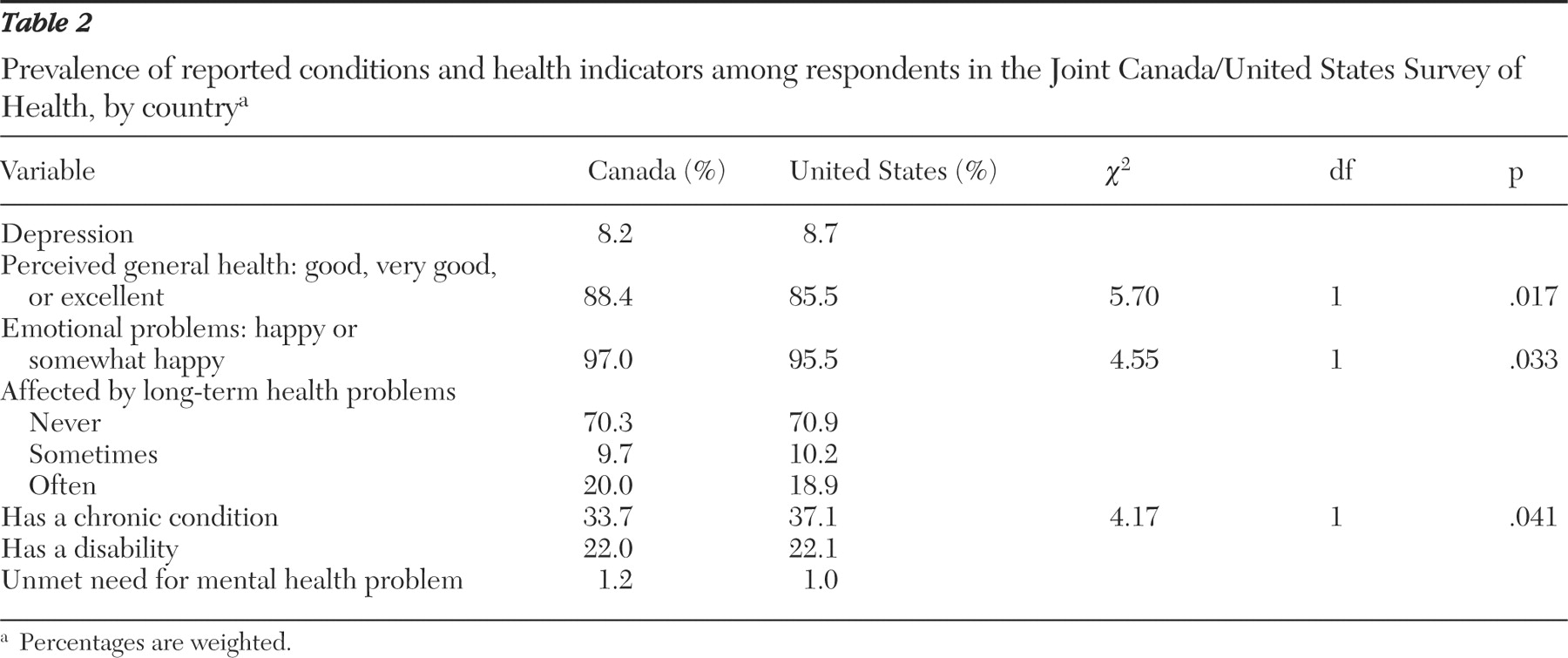

Despite response differences, the JCUSH survey respondents sampled were a representative group of the Canadian and U.S. general populations. The past-year prevalence of major depression was 8.2% in Canada, and it was 8.7% in the United States. The Canadian estimate is similar to the one reported for the annual prevalence of major depression (7.4%) from cycle 1.1 (2000-2001) of the CCHS, which also used the CIDI-SF (

22 ). The U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication, which surveyed a household population aged 18 years and older, similarly reported the 12-month prevalence of a mood disorder at 9.5% (

26 ). Furthermore, the recent cycle 1.2 (2002) of the CCHS Mental Health and Well-Being Survey, which used the full CIDI, reported a 12-month prevalence of major depression and a manic episode of 4.8% and 1.0%, respectively, in a household sample aged 15 years and older (

27 ). Although the CIDI-SF has been shown to overestimate the prevalence of depression (

22 ), its use in within-study comparisons remains relevant for evaluative purposes.

Results presented here were based on data collected from Canadian and U.S. respondents in a single survey in which all respondents were administered the same items and were probed to the same degree. This design comparability increases the validity of the comparisons between the two countries. Canadian and U.S. samples did not differ with respect to reported disability, the impact of health problems on daily life, and reported unmet need as a result of mental health problems. More information on the direct comparisons of health indicators is presented elsewhere (

16 ).

In this study 12-month prevalence rates of depression were similar between Canada and the United States, and this finding was true for any age group or sex (

16 ). In the United States depression, however, was associated with medical insurance, which agrees with recent studies highlighting the inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and mental illnesses (

28,

29 ).

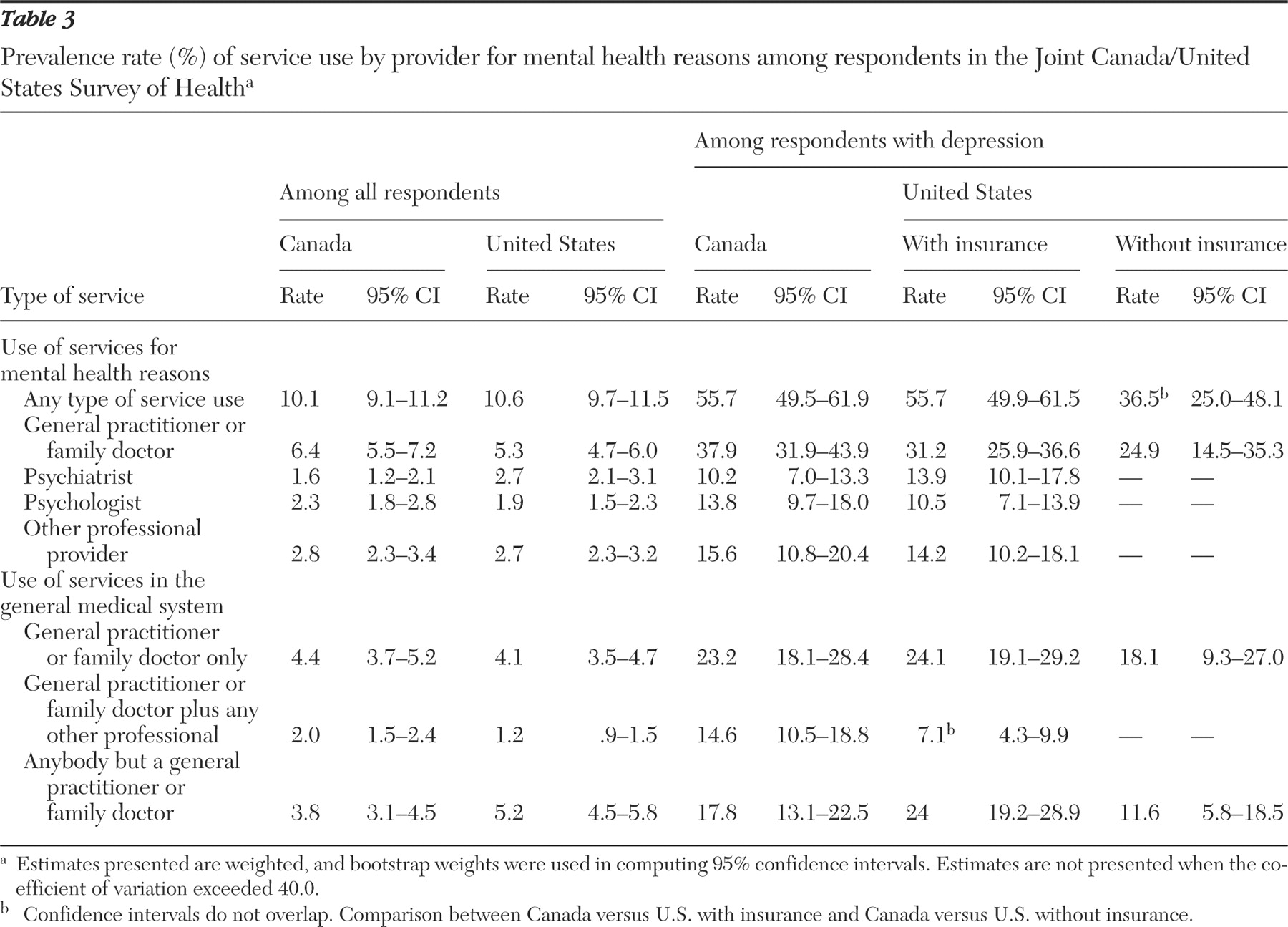

In the 12-month prevalence of any type of service use for mental health reasons, among all respondents, no difference was observed between countries, or within the United States, after the analyses adjusted for medical insurance and for other determinant factors. As with previous studies, in both the United States and Canada respondents consulted mostly with a general practitioner or family doctor for mental health reasons (

4,

5,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34 ). Although findings were not statistically significant (p=.051), our study showed that U.S. citizens were more likely than Canadians to consult a psychiatrist and any other professional but a general practitioner for mental health reasons. This may be due to differing public perceptions, in which U.S. citizens think mental health should be dealt with and care sought strictly at a specialty level and that mental health issues should not be divulged at the primary-care level because of social stigma. In contrast, in Canada general practitioners are usually the gatekeepers to other health services and, therefore, may limit the number of referrals to psychiatrists.

A recent study by Mojtabai and Olfson (

35 ), which also used data from the JCUSH survey on cases with probable depression, found that there was no difference in the prevalence of contacts with any provider for mental health reasons between the United States and Canada. Our study goes a step further and considers medical insurance in the United States as a potential determinant of service use. However, when medical insurance was considered in our study, the analysis of cases with depression showed that U.S. respondents without medical insurance were less likely than Canadians and U.S. respondents with medical insurance to use any type of mental health service. This further highlights the importance of increasing access to services for mental health reasons among those without medical insurance, persons who, as previously reported, are also more likely to meet the criteria for depression.

Among respondents with depression, Canadians were twice as likely as U.S. respondents to consult in the past year with a general practitioner or family doctor plus another type of health professional, as has been reported in another study (

35 ), and this finding was true regardless of whether U.S. respondents had medical insurance. This difference may in part be explained by the inadequate referral system between the general and specialty mental health systems in the United States, as concluded from the results of a telephone survey that found that more than half of primary care physicians reported having difficulties in obtaining psychiatric and outpatient mental health referrals (

36 ). In Canada a national initiative has been under way to encourage collaboration between the primary and mental health care sectors (

37 ), which may encourage physicians to refer and support a collaborative model of mental health care.

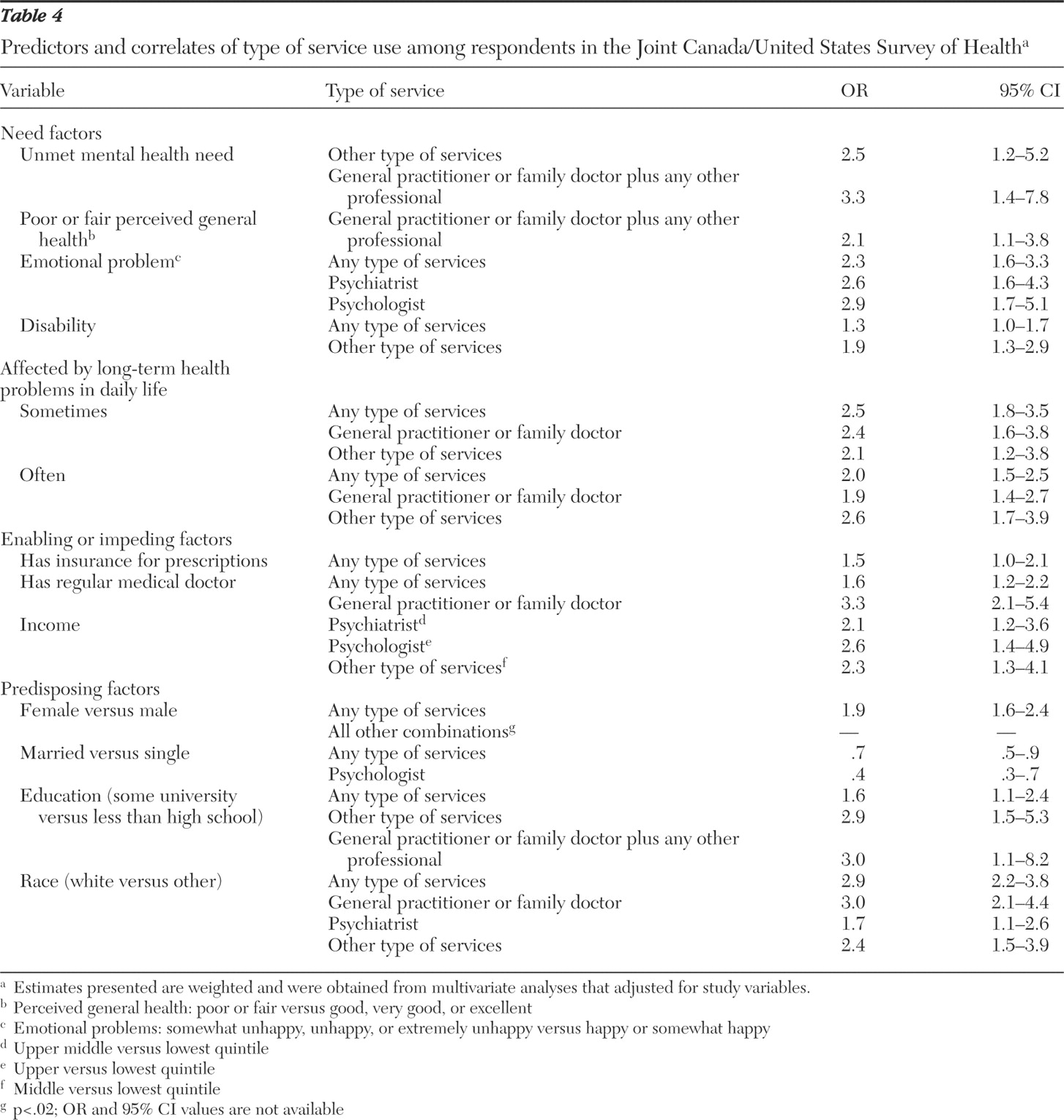

With respect to determinants of service use, our results showed that among the need factors, depression was the most significant and common predictor of overall use of services. Respondents reporting an unmet mental health or emotional need were more likely to use other types of services (for example, from a nurse, social worker, or counselor) and to consult a general practitioner or family doctor plus at least one other type of health professional, which has been similarly reported in Australia (

38 ).

Income in this study was positively associated with consulting a psychiatrist or psychologist and negatively associated with the use of other types of services. Others have similarly reported that income and socioeconomic status play a role in the type of mental health treatment sought (

14,

15,

39 ).

Among the predisposing factors studied, sex, race, education, and marital status were important determinants of service use for mental health reasons. Females were more likely than males to use services (

13,

30,

31,

34,

40,

41 ), as were respondents who were married as opposed to the single or never married (

14,

31,

32,

41 ) and those with a university degree as opposed to respondents having less than a high school education (

42,

43 ). These findings are nearly universal in the broader health services utilization literature. Race also played a role in service use for mental health reasons. Previous reports suggest that differences in perceived acceptability in using health services for mental health reasons may in part explain the difference in service use for ethnic groups (

31 ) and for males (

32,

44 ).

In both countries, sex, education, and race are important factors in service use for mental health reasons. White males and Native American Indians compose a majority of suicide deaths in both countries, where suicide rates have reached 11.9 per 100,000 in Canada (

45 ) and 11.0 per 100,000 in the United States (

46 ). Public health efforts to increase access to mental health services among vulnerable and at-risk populations should be furthered. Mental health education and awareness programs should be sensitive to target populations with respect to sex and cultural factors.

Country-specific differences between determinants and mental health service use suggest that U.S. respondents with no medical insurance and a mental health need (probable depression, emotional need, or perceived poor general health) were less likely to use services than Canadians and those without a need. This finding suggests a more important and positive association of a mental health need and depression and seeking mental health services in Canada. Similarly, Mojtabai and Olfson (

35 ) reported that depression severity, as a function of the number of depressive symptoms, was more closely associated with mental health service use in Canada than in the United States.

Our analyses were based on data collected from the JCUSH survey. The data held a number of limitations, as reported (

16 ), which should be considered when interpreting the results. First, study participation was elicited through random-digit dialing and therefore excluded a small portion of households that did not have a telephone (4.4% in the United States and 1.8% in Canada). Although no information was available to compare these households with those of the general population, it has been estimated that those without a telephone belong to lower income levels.

Second, the target sample excluded people residing in institutions, those living in Canadian and U.S. territories, and the homeless. These excluded groups tend to have specific types of mental health issues and different patterns of health service use; therefore, our results may not entirely apply to these populations.

Third, the response rates were low: 66% of Canadian residents and 50% of U.S. residents participated. The agencies did not keep any information (sociodemographic characteristics or health status) concerning nonrespondents, and therefore, any attempt to describe this selection bias was not possible. We therefore attempted to present data on how representative these samples were by considering various characteristics of their respective general populations. The samples did not differ significantly on a number of population characteristics, which adds to the generalizability of the results. However, the lower participation rate in the United States may have underestimated existing differences between the two countries. A higher percentage (about 5%) of the U.S. sample had medical insurance than reported for the U.S. general population, which may have attenuated any differences that might have existed in the prevalence of service use had the U.S. group without medical insurance not been underrepresented. Further, it is important to note that insurance coverage in Canada was assumed to be 100%, which is not entirely accurate because nonphysician services remain an out-of-pocket cost. It was not possible to estimate the number of Canadians with private insurance plans, usually through employee assistance programs, that would cover part of these costs.

Fourth, the results were based on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall bias as well as a social desirability bias. Because the same survey methods were used in both countries, these information biases are most likely nondifferential and would underestimate any difference between the two countries.

Fifth, depression was measured with the CIDI-SF version, which tends to overestimate depression, compared with the full CIDI or the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, which is regarded as a diagnostic gold standard (

47 ). However, the CIDI-SF remains a relevant tool when carrying out within-study comparisons, as is the case here (

22 ).

Sixth, the measure of mental health service use was limited to whether the respondent had seen or talked on the telephone to a health professional for an emotional or mental health reason. This definition did not include whether the respondent was taking any medication for mental health reasons or the quality or adequacy of care received. Therefore, the definition of mental health service used in this study did not permit us to determine whether proper and adequate mental health care was received.

Finally, although these cross-sectional surveys give a picture of the prevalence of mental disorders and the type of provider seen for mental health service use, future longitudinal studies can clarify the temporal relationship between health determinants and type of provider seen, which can elucidate the effectiveness of care received or sought. This will also give a clearer picture as to drivers of specific types of provider combinations of mental health service use during a given year. Future research may also consider the comparison between determinants of use with respect to psychiatric versus nonpsychiatric disorders, which may lead to a better understanding of health service use in regard to population characteristics as well as access to different areas of health services in both countries.