An estimated 44% of U.S. college students are binge drinkers (

1 ). Excessive drinking in late adolescence and early adulthood can have serious consequences, including injuries (

2 ), risky sexual behaviors (

3,

4 ), and poor academic performance (

5 ).

Binge drinking and heavy alcohol use among college students have been studied extensively, and an increasing number of studies have focused on early detection and intervention programs for college students (

6,

7 ). However, alcohol use disorders among college students have received less research attention until recently (

3,

8,

9 ). In particular, little is known about the use of alcohol treatment services among 18- to 22-year-olds.

Studies of use of alcohol treatment services have typically covered a very wide age range rather than focusing specifically on young adults (

10,

11,

12,

13,

14 ). Andersen's behavioral model of health service utilization (

11,

13,

15,

16 ) suggests that the use of treatment services is determined by predisposing characteristics, such as demographic characteristics and attitudes toward treatment or illness; enabling characteristics, such as family income; and needs-related characteristics, such as severity of alcohol problems.

Gender, age group, race or ethnicity, education, marital status, family income, and employment status are reported to be associated with use of alcohol treatment services (

10,

11,

13,

16,

17 ), with some variations by characteristics, such as age and ethnicity (

16,

18,

19 ). Additional characteristics associated with the use of alcohol treatment services include symptoms of alcohol abuse or dependence and comorbid drug use disorders (

17,

18,

20 ).

Because full-time college students, part-time college students, noncollege students (those in school at a grade level below college), and nonstudents may differ in important ways, we examined the following questions among young adults who met criteria for an alcohol use disorder: What personal and clinical characteristics were associated with the receipt of alcohol services, and did this differ by educational status? What personal and clinical characteristics were associated with perceiving a need for alcohol treatment, and did this differ by educational status? Were particular symptoms of alcohol use disorder as specified in

DSM-IV (

21 ) associated with receiving or perceiving a need for alcohol treatment?

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of all young adults ages 18 to 22 (N=11,333), 38% were full-time college students, 7% were part-time college students, 11% were noncollege students, and 45% were nonstudents. These proportions did not vary by gender or age group. Approximately 38% of young adults were from nonwhite minority groups, 9% had ever been married, and 69% were currently employed.

Alcohol use disorders, by college enrollment status

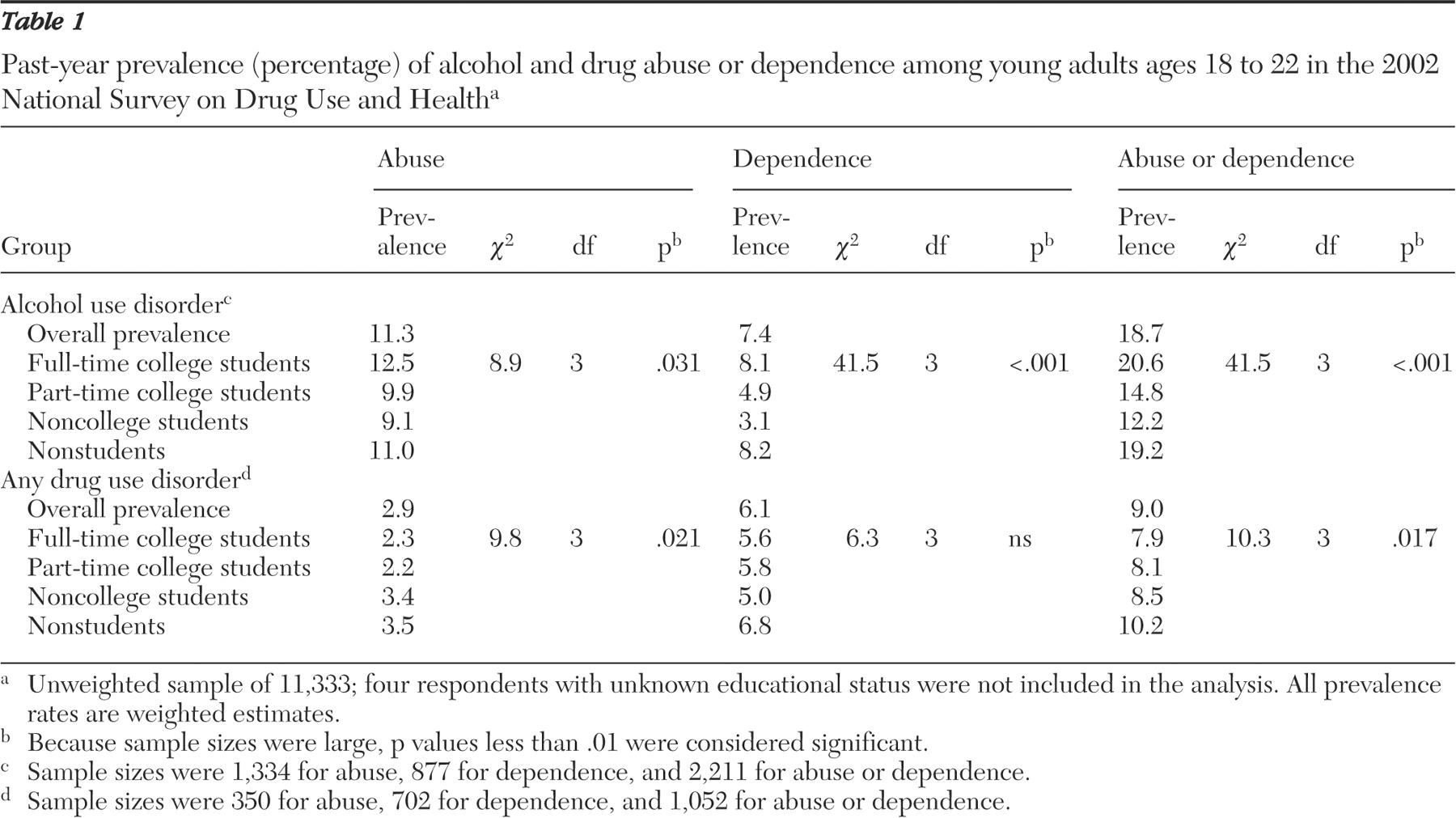

Among all young adults ages 18 to 22, close to 19% met criteria for past-year alcohol use disorders (11.3% for abuse and 7.4% for dependence), and 9% met criteria for past-year drug use disorders (2.9% for abuse and 6.1% for dependence).

Table 1 shows that college enrollment status was associated with alcohol use disorder (

χ 2 =41.54, df=3, p<.001). Full-time college students had a higher prevalence (21%) of alcohol use disorder than part-time college students (15%) and noncollege students (12%). Alcohol dependence was higher among full-time college students (8%) than among other students (3%-5%) but similar to that of nonstudents (8%).

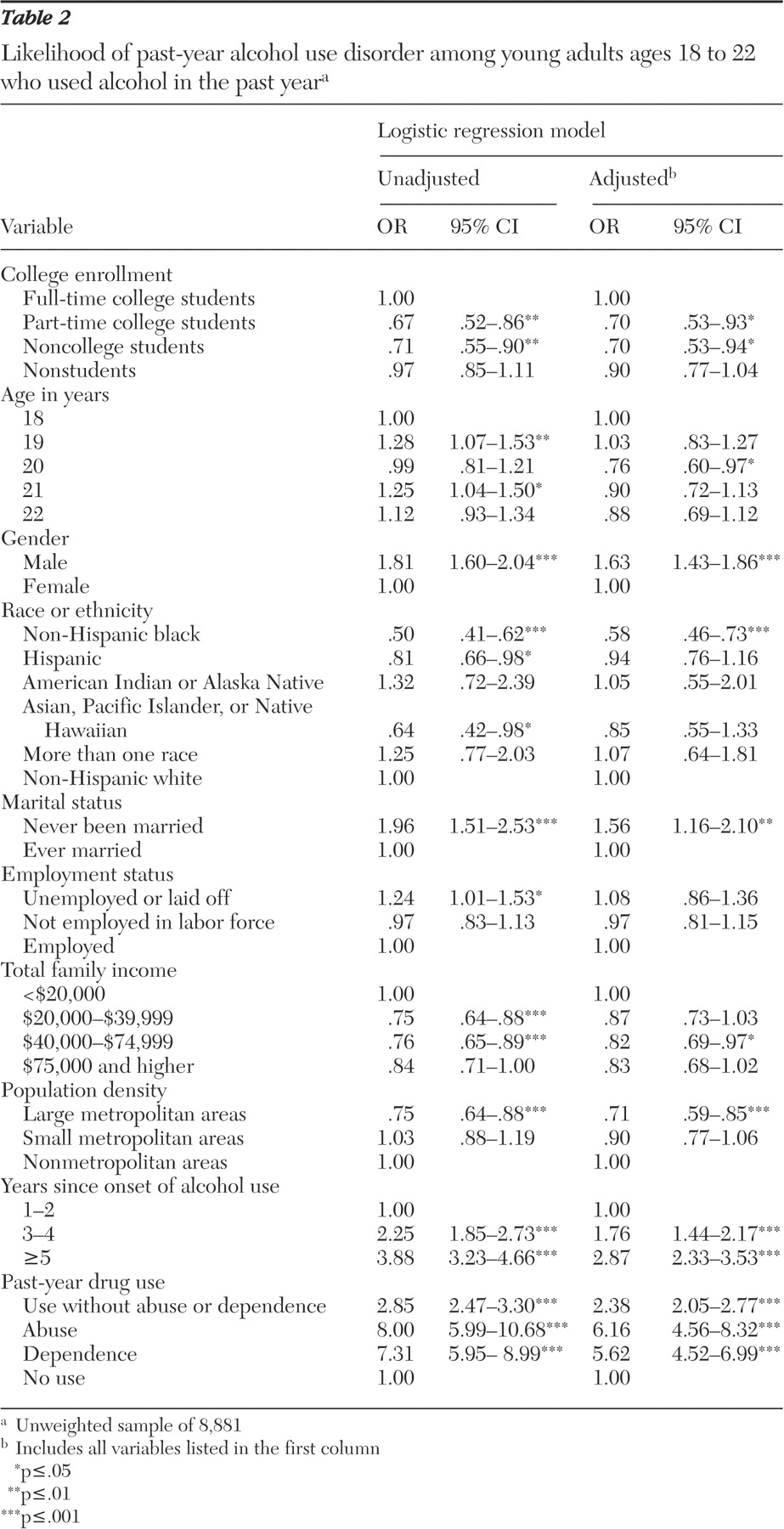

Characteristics associated with alcohol use disorders among past-year alcohol users (N=8,881) are reported in

Table 2 . Part-time college students and noncollege students were less likely than full-time college students to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder, whereas there was no difference in the odds of having an alcohol use disorder between full-time college students and nonstudents.

Men, non-Hispanic white students (compared with non-Hispanic black students), those who had never been married, those in the lowest level of family income (compared with those with a family income between $40,000 and $74,999), and young adults residing in nonmetropolitan areas (compared with those in large metropolitan areas) had increased odds of having alcohol use disorders. More years of alcohol use and having a drug disorder or using drugs were highly associated with alcohol use disorders.

Service utilization, by college enrollment status

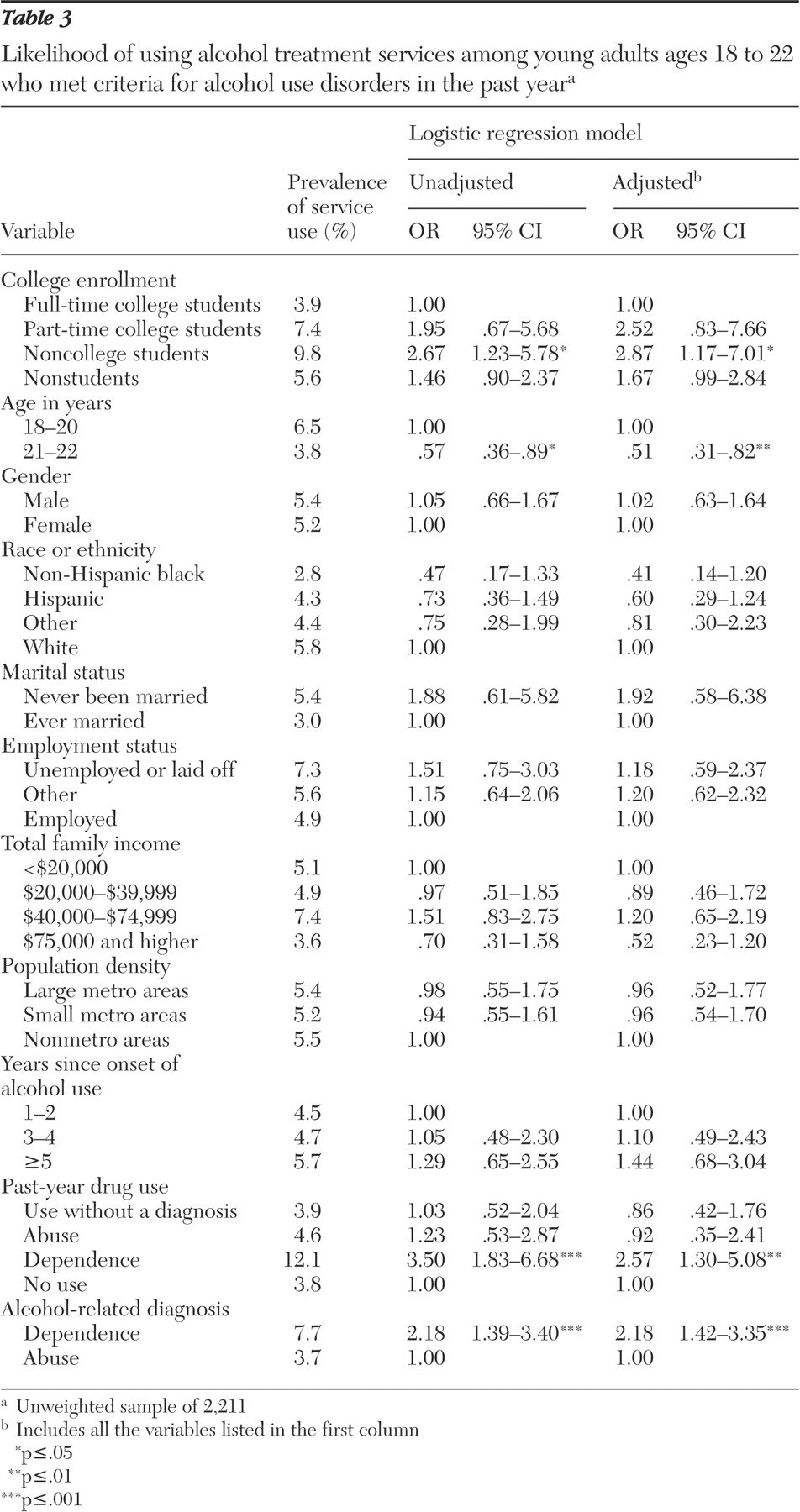

The prevalence and likelihood of past-year use of alcohol treatment services are reported in

Table 3 . Use of specialty alcohol treatment (data not shown) was defined as a subset of overall treatment service use. Among those with an alcohol use disorder, very few full-time college students used services: 3.9% used any services and 1.9% used specialty services. The prevalence for part-time college students was 7.4% and 2.8%, respectively. Noncollege students were slightly more likely than the other groups to use services: 9.8% and 7.3% used any services and specialty services, respectively.

We also examined the prevalence of service use separately for abuse and dependence (data not shown). The overall use of any alcohol services was higher among those with alcohol dependence (7.7%) than among those with alcohol abuse (3.7%). Only 7% of full-time college students with alcohol dependence received any alcohol services in the past year.

Characteristics associated with alcohol service use among 2,211 young adults with an alcohol use disorder in the past year are reported in

Table 3 . Compared with full-time college students, noncollege students were about three times as likely to use any alcohol services (adjusted OR=2.87). There were no differences in service use between full-time college students and the other groups. In addition, young adults ages 21 or 22 were less likely than those of ages 18 to 20 to use any services (adjusted OR=.51). Service use also was associated with alcohol dependence (adjusted OR=2.18) and with comorbid past-year drug dependence (adjusted OR=2.57).

Perceived need for alcohol treatment services

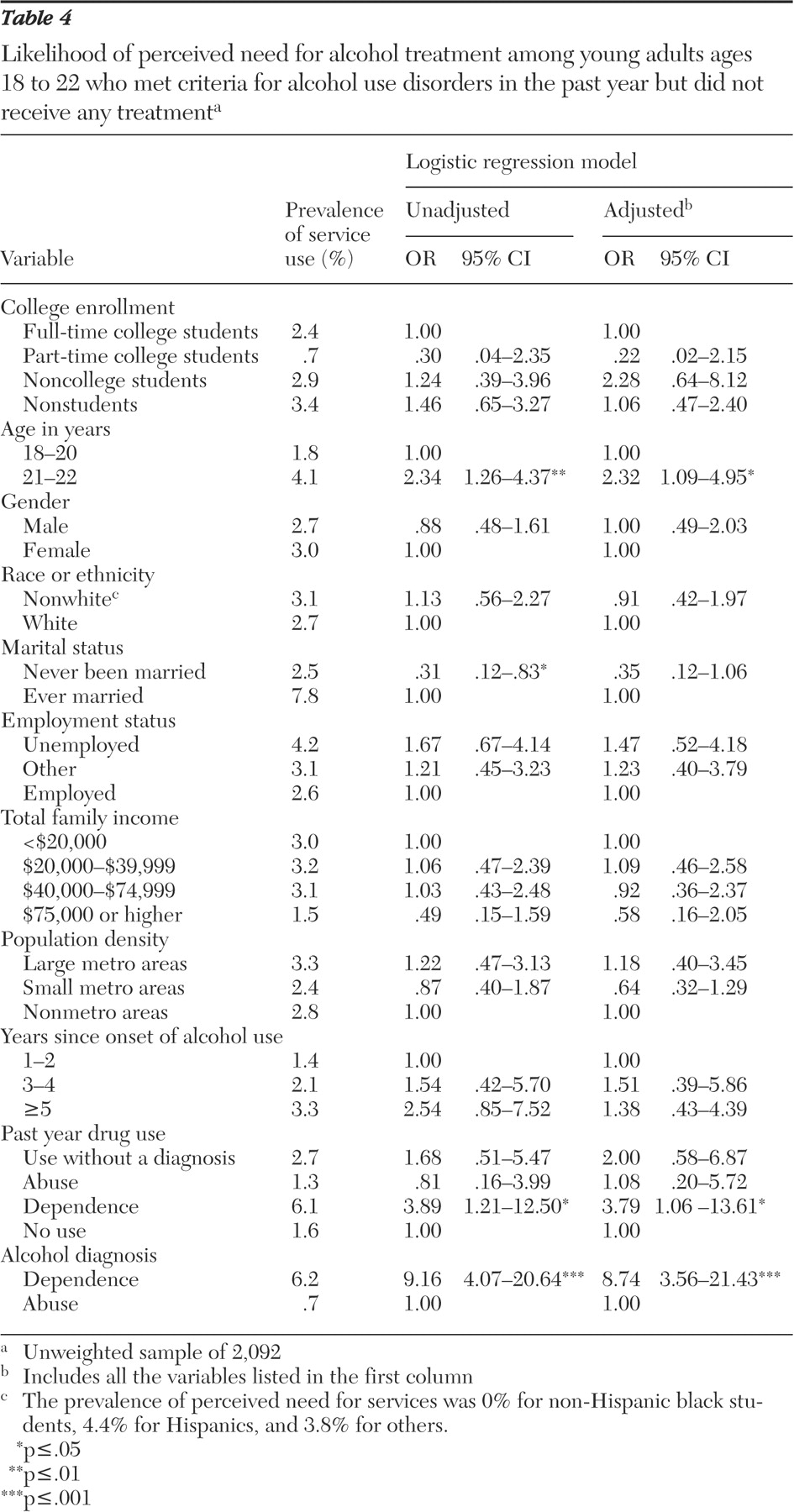

Very few young adults who met criteria for a past-year alcohol use disorder and did not receive any alcohol services in the past year reported needing alcohol services (

Table 4 ). The prevalence of the perceived need for alcohol treatment among young adults with an alcohol use disorder was 2.4% for full-time college students, .7% for part-time college students, 2.9% for noncollege students, and 3.4% for nonstudents. We also found that students with alcohol dependence (6.2%) were more likely than those abusing alcohol (.7%) to perceive the need for such treatment.

ORs of perceived need for alcohol services among 2,092 young adults with a past-year alcohol use disorder who did not receive any alcohol treatment services are reported in

Table 4 . Whereas college enrollment status was not associated with the perceived need for alcohol services, older age (adjusted OR=2.32), alcohol dependence (adjusted OR=8.74), and comorbid drug dependence (adjusted OR=3.79) were associated with increased odds of perceiving a need for such services.

Alcohol use disorder, service use, and perceived need for services

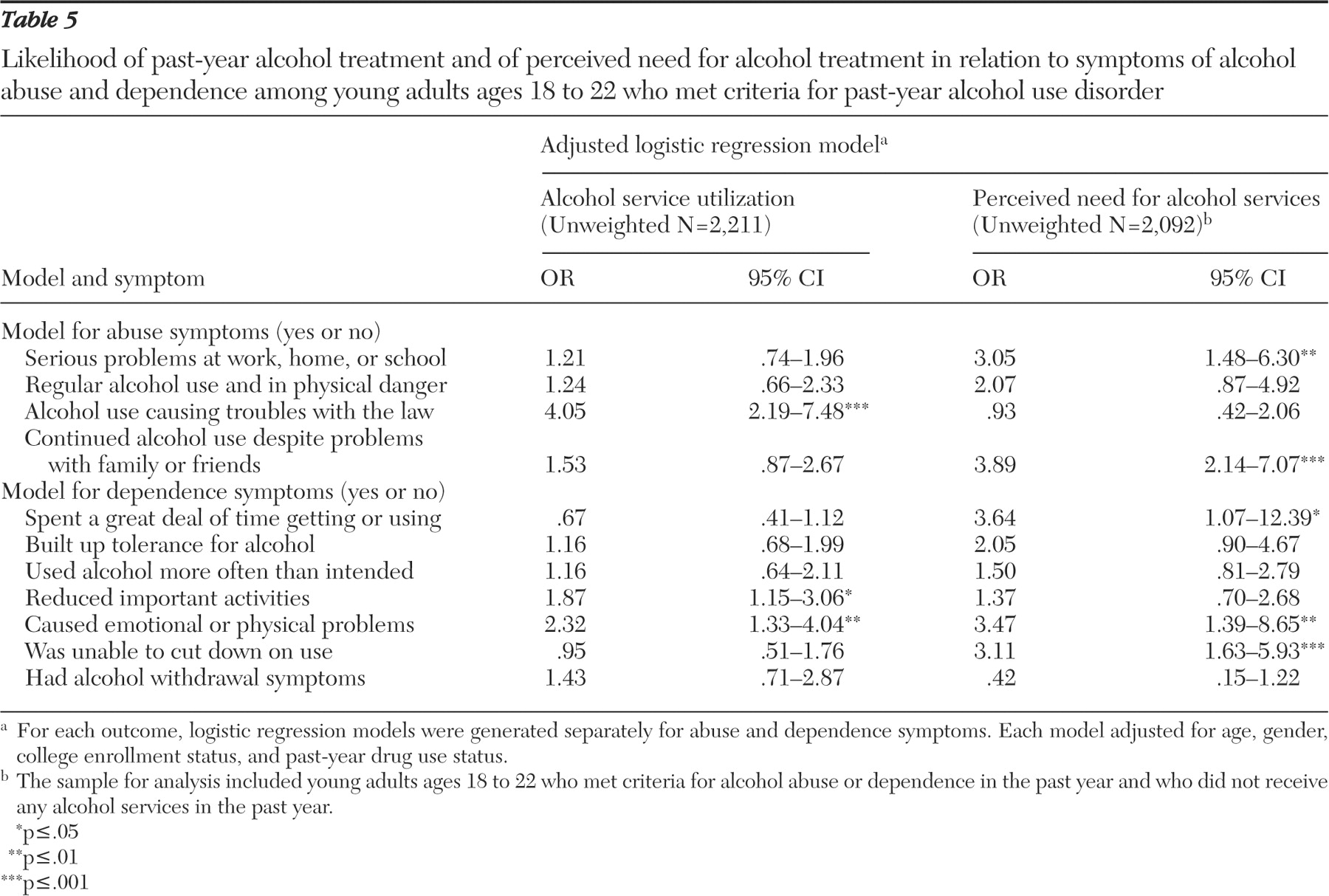

We used logistic regression models separately for abuse and dependence to examine whether specific symptoms of alcohol use disorder were associated with service use and the perceived need for such services (

Table 5 ). Controlling for age, gender, college enrollment, and past-year drug use status—which was associated with alcohol use disorder or service use—we found that "alcohol use causing troubles with the law" was associated with increased use of alcohol services, without a concomitant increase in the perceived need for these services. In addition "continued alcohol use despite problems with family or friends" and "serious problems at work, home, or school" were associated with a perceived need for services.

Alcohol dependence, service use, and perceived need for services

In the model for dependence symptoms, "reduced important activities" and "caused emotional or physical problems" were associated with service use. Significant correlates of a perceived need for alcohol services included "spent a great deal of time getting or using alcohol," "caused emotional or physical problems," and "was unable to cut down on use."

Reasons for not receiving alcohol services

The subsample with an alcohol use disorder who did not receive any alcohol service but reported the perceived need for such services was small, only 46 students. The most common reasons for not using services were "not ready to stop using alcohol and/or drugs" (47%), "having no health care coverage and unable to afford the cost" (19%), "concerned that getting services might cause neighbors and community to have a negative opinion" (18%), and "not knowing where to go to get treatment" (15%).

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of young adults ages 18 to 22, we found a high prevalence of alcohol use disorders and a low prevalence of alcohol service use. About one-fifth of college-age young adults met criteria for a past-year alcohol use disorder, which was higher than estimates for adolescents ages 12 to17 (5%) (

26 ), persons ages 15 to 54 (7%) (

27 ), and adults ages 30 or older (less than 6% for abuse and less than 4% for dependence) (

28 ). Our finding was similar to a recent estimate (18%) among all young adults ages 18 to 24 (

8 ).

Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among part-time and noncollege students was lower than among full-time college students. Part-time and noncollege students are more likely to live with their parents than full-time college students, which may have some protective effects on alcohol abuse (

29 ) because those living with their parents may be more likely to be monitored and less likely to spend long hours with alcohol-using peers or in a context that promotes alcohol use behaviors (such as bars in college towns). The resulting reduction of opportunities for alcohol exposure may contribute to moderation and lessen the risk of alcohol abuse. This explanation is speculative and requires future work to test it. Noncollege students seem to be an important subgroup to study further. They had a lower prevalence of alcohol use disorders than full-time college students but were more likely to receive alcohol services. The reasons why they were still in high school (or technical or vocational schools) were unavailable in the survey.

We also found that full-time college students were as likely as the nonstudent subgroup to have an alcohol use disorder. Frequent alcohol use is associated with increased odds of dropping out of school among high school students, and youths not in school are more likely than those in school to use alcohol (

30,

31 ). Yet some aspects of college-related environments also place college students at risk for alcohol abuse. In particular, full-time college students tend to live away from their parents, to associate with peers who use alcohol regularly, and to be in environments where social activities involve alcohol use, which appear to increase their risk of having an alcohol use disorder (

3,

4,

32 ). However, college-related environments seem to have no significant negative influences on drug use disorders, which had a similar prevalence among all young adults. The reason might be related to the greater social acceptability of alcohol use in American colleges compared with drug use. This hypothesis requires confirmation by studies of students' attitudes toward different licit and illicit substance use.

Our data suggest that entry into alcohol treatment services tends to be associated with drug or alcohol dependence and with legal problems. Among those with legal problems, treatment is often mandated by courts. Similarly, those with comorbid drug use problems may come to the attention of family members, health care providers, or the criminal justice system, who then prompt or coerce the person with the disorder into receiving services (

19,

33,

34,

35 ). Other studies also have suggested that individuals with an alcohol use disorder typically do not seek help until their alcohol use results in substantial problems in their lives (

36,

37 ). Denial of alcohol-related problems and lack of motivation to receive treatment may explain this finding (

38,

39 ). Consistent with other studies (

19,

40,

41 ), the individual's perception that alcohol use is not a problem was a major barrier to alcohol treatment. Our study found that, among those with an alcohol use disorder who did not receive alcohol services in the past year, only 2.4% of full-time college students reported a need for alcohol services. In addition, young people may have financial barriers or may not know where to go for help and how to obtain confidential alcohol treatment (

42,

43 ).

Alternatively, the low prevalence of alcohol treatment use may have resulted, at least in part, from the inclusion of mild cases of alcohol abuse, where the need for treatment is debatable. Such cases might occur when individuals receive a diagnosis of alcohol abuse with only one symptom of abuse, as dictated by

DSM-IV. Although studies have suggested that many adults with an alcohol use disorder eventually get better without receiving treatment (

44 ), treatment or counseling is important for at least some young adults with an alcohol use disorder. In particular, alcohol dependence is more chronic than abuse (

45,

46,

47 ) and may require formal treatment to prevent alcohol-related mental and physical illnesses. Various interventions, including prevention, alcohol treatment services, and harm reduction approaches (such as providing buses on weekend evenings from college towns, where drinking often takes place, to college dormitories), could help reduce substantial direct and indirect consequences of alcohol abuse, including academic problems, violent behaviors, physical injuries, property damage on campuses, and unwanted sexual behaviors, as well as injury and death from driving under the influence of alcohol (

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7 ).

The physiological aspects of alcohol use disorders (withdrawal symptoms) predict the chronicity of alcohol dependence (

48,

49 ), but they were unassociated with alcohol service use or the perceived need for such services in this study. Rather, alcohol-related social and legal problems, as well as the inability to cut down on alcohol use, increased young adults' or others' recognition of having alcohol problems. The low prevalence of service use (5%) among women with an alcohol use disorder also deserves research attention. Young women appear to be more likely than young men to first adopt binge drinking in college (

50 ), and college-attending women get drunk more frequently than non-college-attending women (

9 ).

These findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, NSDUH data, including school enrollment status, are based on respondents' self-reports. Although our key variables referred to past-year behaviors, and NSDUH incorporates computer-assisted interviewing techniques to improve the accuracy of self-reports of substance use behaviors (

24 ), our findings could be influenced by recall and reporting biases.

Second, NSDUH assessments of alcohol use disorders are based on a single structured interview administered by trained interviewers, and diagnoses are not validated by clinicians. This limitation is found in most large-scale epidemiological studies (

51 ). Our estimates of alcohol use disorders are much lower than the estimate (38%) from a survey of college students (

3 ), which suggests that NSDUH is unlikely to largely overestimate the prevalence of alcohol use disorders. Third, the lack of information about the quality of services received prevents our analysis of these variables.

Heavy drinking and alcohol problems increase during the transition into college years (

52 ). The high prevalence of alcohol use disorders among full-time college students and nonstudent young adults calls for continuous efforts to reduce alcohol use and alcohol-related harm. Both primary prevention and focused interventions have been recommended (

32,

53,

54,

55 ). Interventions to motivate treatment use among young adults with an alcohol use disorder may be more effective if they build on the symptoms that increase the perceived need for treatment, including associated emotional problems or the inability to reduce alcohol use. Increased availability of and access to community- and college-based alcohol-screening programs may be an effective way to identify individuals with harmful alcohol use behaviors, to offer alcohol-related education, and to refer them to appropriate treatment service programs (

40 ).