In this article, we examine the correlates of adverse childhood events in a large, multisite sample of public-sector mental health clients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The long-term health implications of adverse childhood events are becoming better understood in the general population. However, no published studies have reported on this relationship among people with schizophrenia. At the same time, the few available studies suggest that people with severe mental illness often experience adverse childhood events, including childhood sexual and physical abuse, neglect, witnessing domestic violence, and out-of-home placement (

1,

2,

3 ). In addition, people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders may be more vulnerable to the impact of such events (

1,

3,

4 ), and they are often characterized as having worse physical health and mental health functioning than the general population (

5 ).

National surveys report that adverse events in childhood are common. Adverse events represent a broader category than trauma per se, which is defined by criteria specified in

DSM-IV (

6 ) and must involve actual or threatened death or serious injury or a threat to physical integrity. Adverse events also may include nontraumatic stressors, such as parental divorce or placement outside of the home. Using the more inclusive category of adverse events, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (

7 ) found that 50% of respondents reported experiencing two or more such events, including physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; neglect; parental substance abuse or mental illness; witnessing domestic violence; or the loss of a parent. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study (

8 ), which was conducted in a primary care setting, found that more than half of the sample had experienced at least one kind of adverse event in childhood and that 25% reported more than two types of events. Results from these studies also suggest that childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction often occur together. For example, in the ACE study, 80% of individuals who were sexually abused in childhood reported at least one other type of adverse childhood experience, and 55% reported two or more types of other adverse experiences (

8 ). Childhood adversity is associated with a broad range of negative health and mental health outcomes, both in childhood and among adult survivors.

There is emerging evidence that childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse are related to more severe symptoms among people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses (

9,

10,

11,

12 ). However, little research has examined the relationship between the broad spectrum of adverse experiences in childhood and clinical, functional, and health outcomes of adults with schizophrenia. Studies to date have been limited by small samples (

5 ) and have not examined the impact of cumulative exposure to adverse events in this population. With this study we aimed to examine the cumulative effects of these associations in a large, multisite sample.

Correlates of adverse childhood events among adults

Childhood abuse has been linked to increased medical problems in adulthood, including chronic fatigue syndrome, lung disease, autoimmune disorders, diabetes, migraines, gastrointestinal disorders, and ulcers (

27,

28,

29,

30 ). Findings from a number of studies indicate correlations between childhood abuse and increased rates of adult psychiatric disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use disorders, borderline personality disorder, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, eating disorder, panic disorder, and antisocial personality disorder (

2,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36 ).

The experience of prolonged foster care (five or more years) is associated with poorer social functioning among adults (

37 ) and with elevated rates of various psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses. These include increased self-destructive and high-risk behaviors, substance use, depression and other mood disorders, and anxiety disorders (

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43 ). Bereavement in childhood also has been reported to be related to depression in adulthood (

44,

45 ).

In addition to research showing associations between specific types of childhood adversity and physical and mental health functioning, there is evidence that the total cumulative exposure to adverse childhood events is related to several negative outcomes. For example, the ACE study found a strong and graded relationship between the amount of exposure to adverse childhood events and rates of substance use disorders, suicide attempts, and multiple sexual partners in adulthood. In addition, cumulative exposure to adverse childhood events predicted adult health problems, such as sexually transmitted diseases, heart disease, and cancer (

8 ). These findings are consistent with those reported in the NCS study, which reported that total adverse childhood event exposure was correlated with increased rates of mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders in adulthood (

7 ).

On the basis of major research in the general population (

46 ), we hypothesized that greater exposure to adverse experiences in childhood would be related to worse functioning across several domains among people with schizophrenia, including psychiatric problems, substance abuse, physical health problems, and social functioning.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 624 adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder drawn from a larger investigation (N=1,152) of risky behavior and sexually transmitted diseases among women and men with severe mental illness (

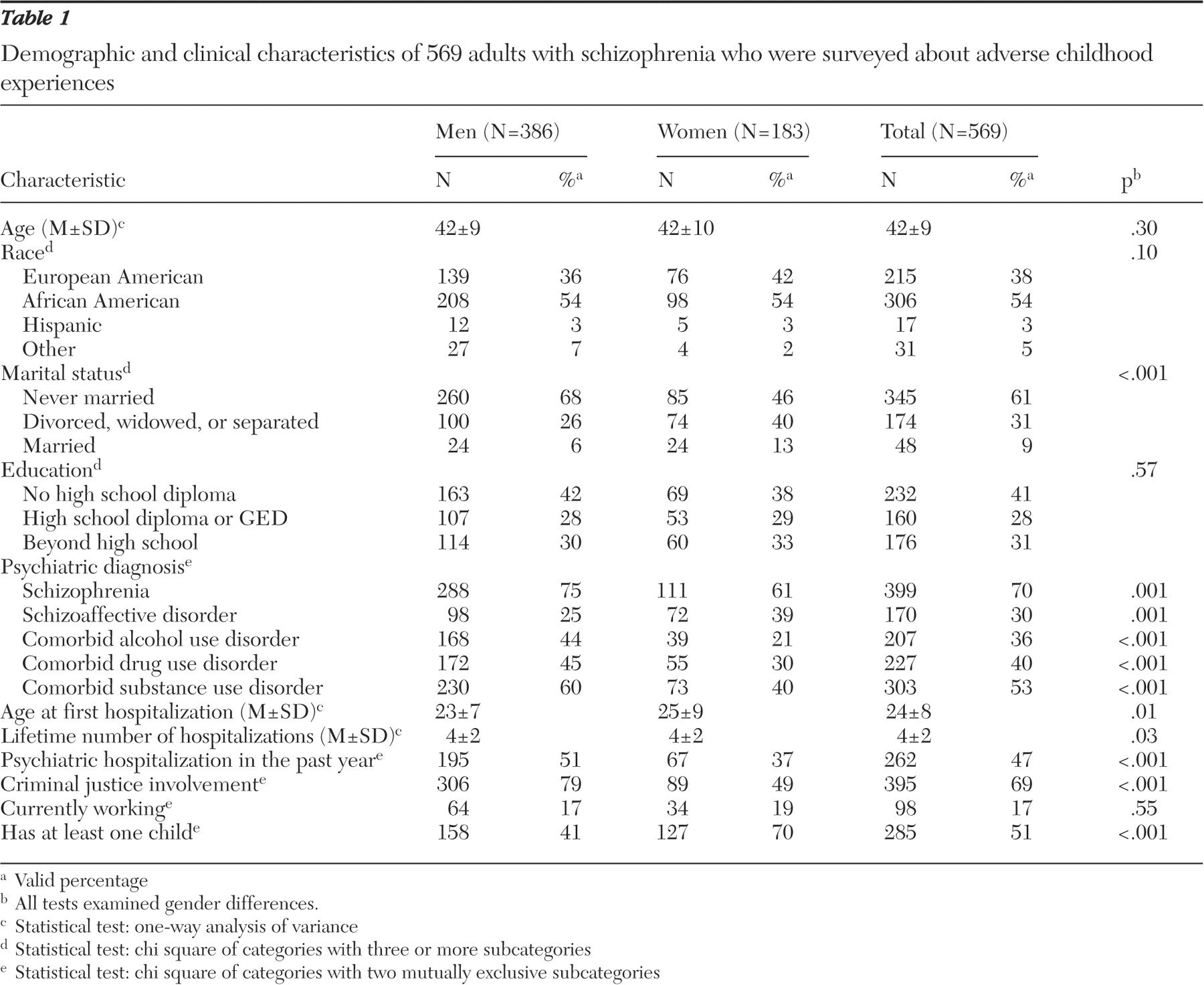

47 ). Participants entered the study between June 1997 and December 1998. The larger sample also included persons with affective disorders, chronic PTSD, and other diagnoses and who met state criteria for severe mental illness. However, the analyses presented in this article included only those with primary schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses. All participants were receiving treatment through the public mental health systems of Connecticut, Maryland, New Hampshire, or North Carolina, and study procedures were approved by all relevant institutional review boards. The settings from which they were recruited were diverse in that the mental health centers were located in rural, urban, and small metropolitan areas. Among the 624 persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders, 569 had complete data on adverse childhood events, which could be assessed and were included in the analyses. Characteristics of the sample are described in

Table 1 .

Measures

This study assessed psychiatric diagnosis, adverse childhood events, psychiatric problems, substance abuse, physical health, and social functioning through chart review, structured expert ratings, and standardized self-reports.

Psychiatric diagnosis. Diagnoses were ascertained with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (46) for 219 participants (19% of the sample), and chart diagnoses for the rest of the sample. Good agreement was found between SCID and chart diagnoses for those clients assessed by SCID ( κ =.72), which supports the general reliability of chart diagnoses for the broad purposes of the study.

Adverse childhood events. Standardized, self-report measures were administered to participants in an interview format to assess childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and loss that occurred during the first 16 years of life.

Childhood sexual abuse was assessed with the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire (

48 ). This self-report scale identifies ten categories of increasingly invasive sexual experiences. This scale has been shown to have good test-retest reliability for both women and men with serious mental illness (

49 ). Participants were considered to have experienced childhood sexual abuse if they responded affirmatively to any of the six items involving physical sexual contact.

Childhood physical abuse was assessed by the three most severe items from the violence subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scales (

50,

51 ), a widely used measure of domestic violence. An affirmative response on any of the three questions was used to indicate child physical abuse (being hit, being knocked down or thrown, and being burned or scalded on purpose).

Parental separation or divorce was defined by a response of yes to the question, "When you were growing up, did your parents/caretakers get a divorce or separation?"

Parental mental illness was defined by an affirmative response to the question, "When you were growing up, did your parent(s)/caretaker(s) ever see a counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist, or go to a mental hospital, or take medication for an emotional problem?"

Domestic violence was determined by the following item: "When you were growing up, did you see or hear your parents/caretakers arguing or fighting a lot?"

Foster care and kinship care were assessed by two questions that asked the respondent whether she or he was placed in an orphanage, foster home, boys' home, reformatory, detention home, or jail or similar placement, or sent to live with relatives, family friends, or other people.

Parental death was based on client self-report of whether the client's father or mother died before the person turned 16.

Psychiatric problems

Health-related quality of life was assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (

52 ). The SF-12 consists of items assessing physical and mental health and yields two summary scores: the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS). Scoring is normatively based, with a mean±SD of 50±10; higher scores indicate better health. The SF-12 is reliable and valid in general and medical populations (

52 ), as well as for people with severe mental illness (

53 ).

PTSD was assessed with the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (

54 ), a self-report screening measure for PTSD. The PCL includes 17 questions, one for each

DSM-IV PTSD symptom, requiring the respondent to rate the severity of each symptom over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. PTSD diagnoses are made if at least one criterion B (intrusive) symptom, three criterion C (avoidant) symptoms, and two criterion D (hyperarousal) symptoms are rated at 3 or above on the Likert scale. The PCL has strong test-retest reliability and convergent validity for people with severe mental illness (

55 ).

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with a subset of items from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (

56 ). The BPRS is a widely used interview for assessing psychiatric symptoms among persons with severe mental illness. The instrument includes 24 items, of which ten items are based on observation of the client alone. Because of interview length and concerns about client burden, only the observational items on the BPRS were included in this study, and these included items from three of the four factors reported by Thomas and colleagues (

57 ): thought disturbance, animation, and apathy.

Hospitalization history was measured by the age at first hospitalization, the lifetime number of psychiatric hospitalizations, and the number of hospitalizations in the prior year.

Substance abuse

Current alcohol and drug use disorders were identified through a combination of the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI) (

58 ) and chart or SCID diagnosis. The DALI is an 18-item screening tool for substance use disorders (abuse or dependence) that was specifically developed and validated for persons with severe mental illness. It has high classification accuracy for

DSM-IV substance use disorders of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine. Cutoff scores have been developed with an empirically derived algorithm. Clients were categorized as having a substance use disorder if either the DALI or diagnosis (via chart or SCID) was positive for a substance use disorder.

Physical health outcomes

Physical health was assessed with items from the Piedmont Health Survey (

59 ). Questions were asked about the following chronic medical problems: asthma, diabetes, heart trouble, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, lung disease, ulcers, stroke, epilepsy, head injury, and infectious diseases (such as sexually transmitted diseases and hepatitis). The problems endorsed were summed to form an overall measure of health problems. Participants also were asked to report for the past six months the number of times they had received care for a physical health problem and the number of days hospitalized for physical health problems. Health-related limitations were assessed by the PCS of the SF-12 (

52 ). Scoring is normatively based, with a mean of 50±10; higher scores indicate better health.

Social functioning

Homelessness was defined as having no regular residence or as living in a shelter or on the street over the past six months.

Poverty status was based on past-year income and was determined by using the 1999 guidelines of the Department of Health and Human Services. These guidelines take into account income, marital status, and number of children.

Criminal justice involvement was defined as having ever been arrested for an alcohol offense, a drug offense, or a driving offense; for writing bad checks, shoplifting, loitering, trespassing, or being a public nuisance; physical or sexual assault against someone; or other miscellaneous offenses.

Work functioning was defined by whether the client was working at the time of the survey and whether the client had worked in the past year.

Overall functioning was assessed with the Global Assessment Scale (

60 ). Scores on this scale range from 0 to 100 points. The measure assesses overall functional and symptomatic adjustment, with higher scores reflecting better functioning. Scores under 41, which represent "impairment in reality testing or communication" or "major impairment in several areas," were considered indicative of poor functioning.

Parental status was defined as having at least one child.

Procedure

After giving informed consent, respondents participated in structured interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes, received pretest counseling for HIV-AIDS, and provided blood specimens as part of a screening for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. All participants were paid $35 and were provided with test results, posttest counseling, and referrals for follow-up testing and treatment, as needed. Permission also was obtained for chart review and obtaining information from treatment providers.

Statistical analyses

Prevalence rates of adverse events in childhood were computed first, followed by examination of the association between different types of adverse events. The association between cumulative number of adverse events and functional outcomes was then examined by performing logistic regression analyses, which controlled for demographic characteristics (gender, age, and race). Because of the large number of tests, we report significance only when p<.01.

Results

Prevalence of childhood adversities

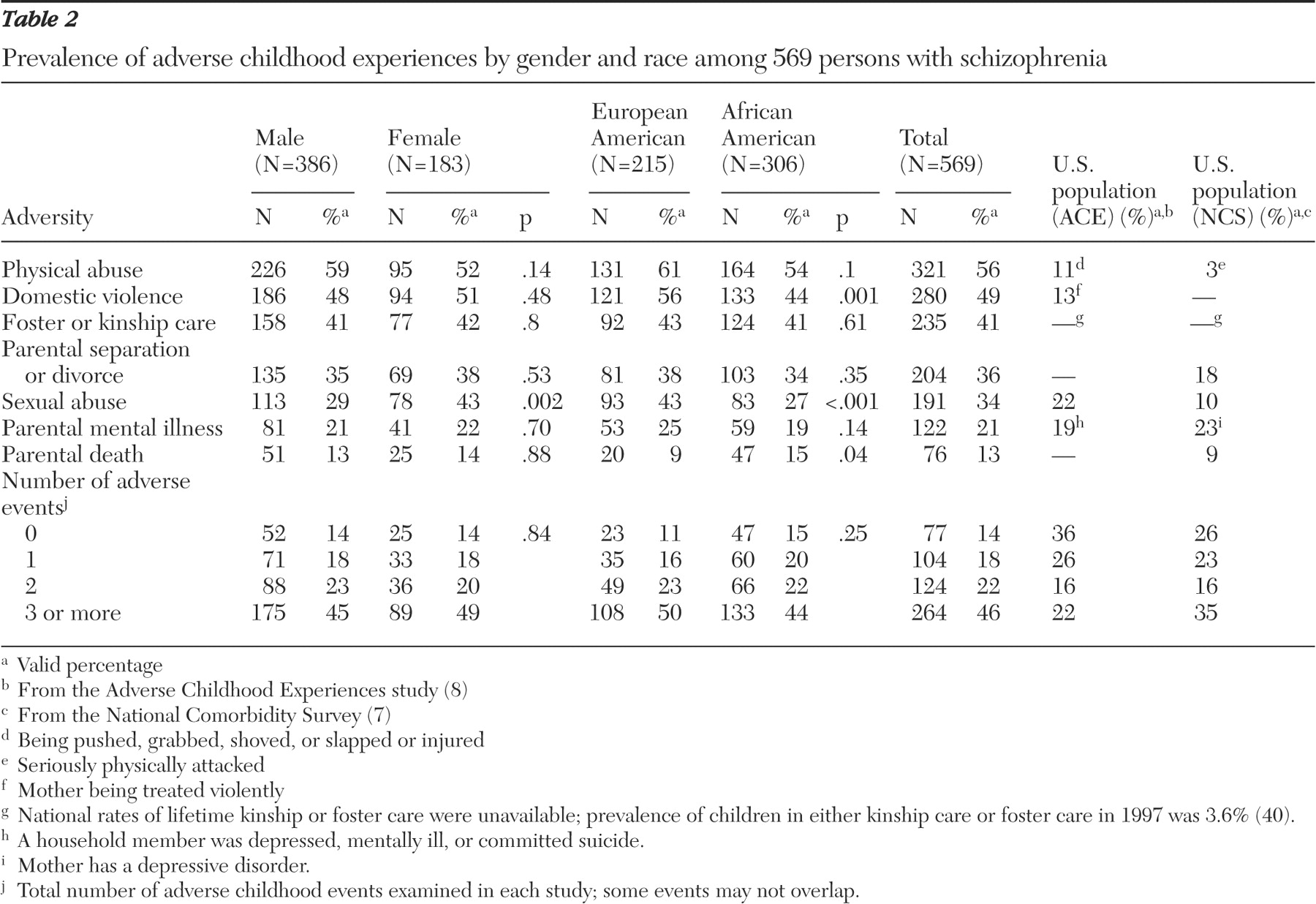

Among the 569 adults with schizophrenia in this study, only 14% reported that they had experienced no adverse childhood events, whereas 18% reported one event and 46% had experienced three or more events. In the ACE and NCS studies, by comparison, about one-fifth and one-third of respondents, respectively, had experienced more than two adverse events, compared with about half the persons in our study. These results are summarized in

Table 2 .

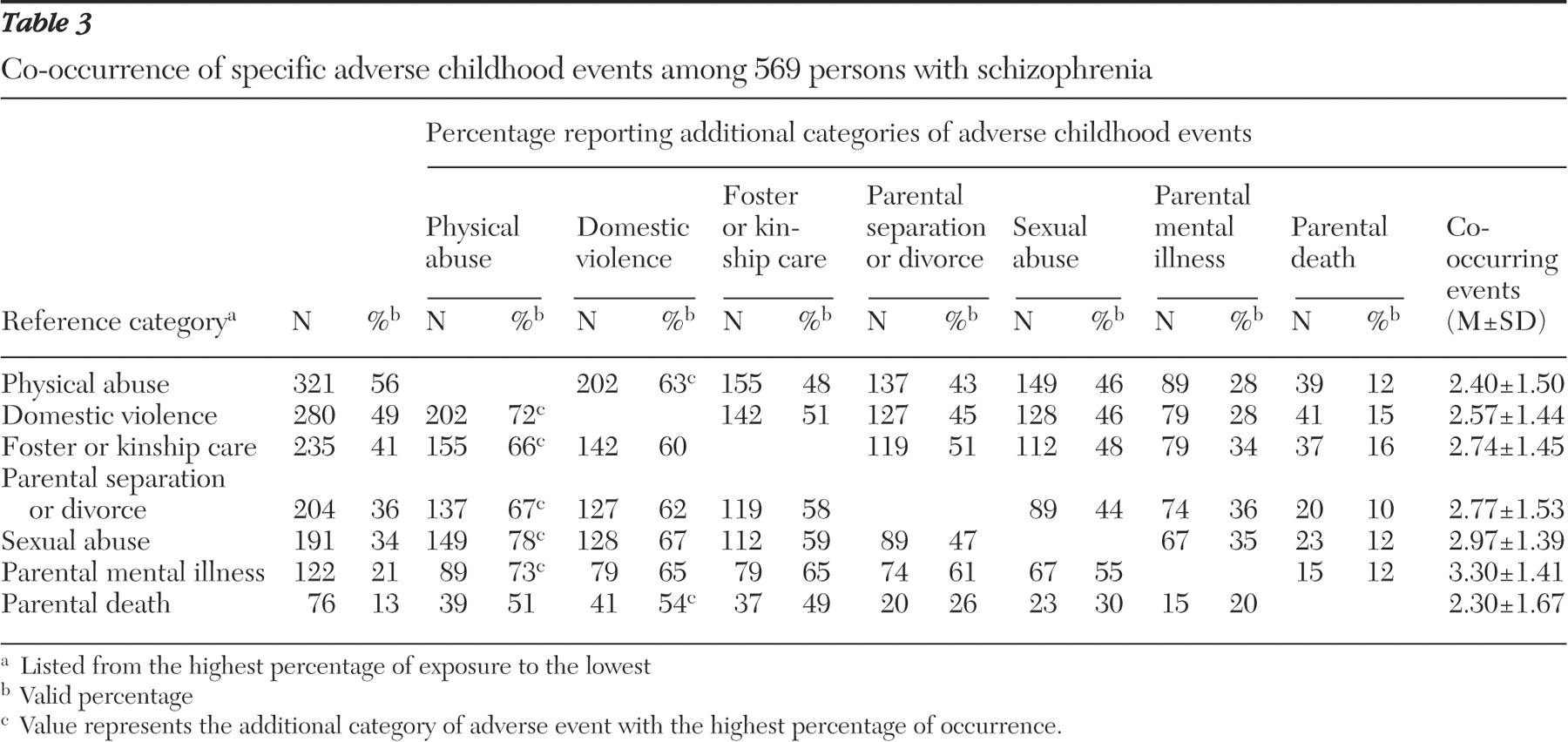

Table 3 summarizes the co-occurrence of different adverse events in childhood. The most common form of adverse childhood event was child physical abuse, followed by witnessing domestic violence, foster or kinship care, parental separation or divorce, child sexual abuse, parental mental illness, and finally, parental death. Most clients who had experienced one adverse event had also experienced between two and three other events. For example, for those who had mentally ill parents, more than half also experienced parental divorce, foster care, and childhood physical and sexual abuse. For those who had experienced sexual abuse as children, more than half also experienced childhood physical abuse, witnessed domestic abuse, and were placed in foster care.

Adverse childhood events and functional outcomes

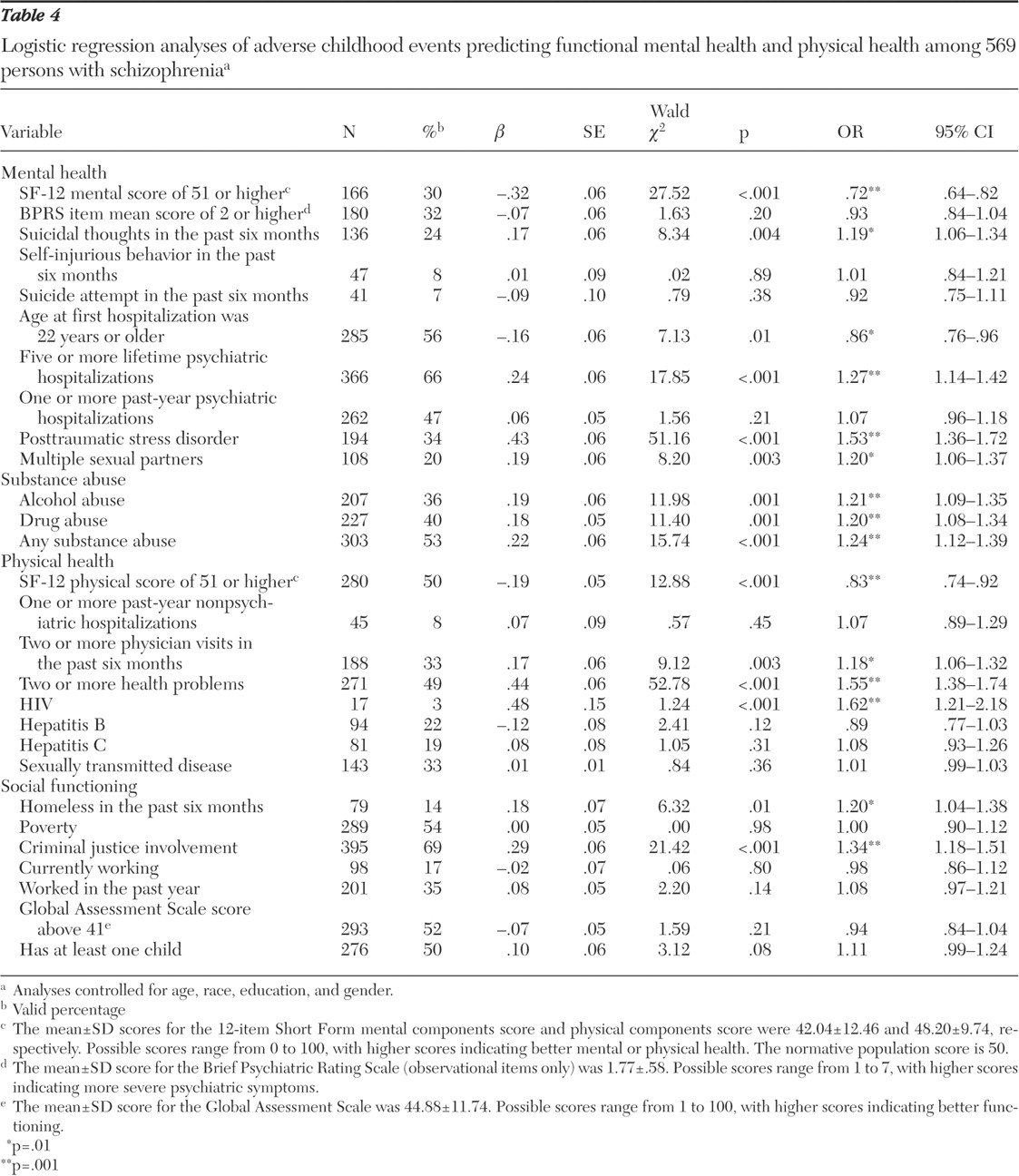

The results of the logistic regression analyses evaluating the associations between cumulative exposure to adverse childhood events and hypothesized outcomes are summarized in

Table 4 . As shown, adverse childhood events were significantly related to six of the ten measures of psychiatric disorder, the exceptions being BPRS score, recent psychiatric hospitalization, and recent self-injurious or suicidal behavior. All measures of substance abuse were significantly related to cumulative number of adverse childhood events. Adverse childhood events were significantly related to four of eight health functioning outcomes, including physician visits, health problems, and most strongly, HIV infection. Finally, with respect to social functioning, adverse events in childhood were related to homelessness and criminal justice system involvement but not to work, poverty, parental status, or overall functioning.

Discussion

There are several limitations to this study. This was a retrospective study; thus underreporting of adverse childhood events may have occurred. Longitudinal follow-up of adults whose childhood abuse was documented has shown that their retrospective reports of childhood abuse are likely to underestimate the actual occurrence (

61,

62 ). In addition, although a large, multisite sample was used, it was nonetheless a convenience sample and may not be representative of all clients of the public mental health system in this country. For example, the sample underrepresents the Hispanic population. Finally, the measures used in this study also were not identical to those used in the NCS and ACE studies, so comparisons are somewhat approximate.

The prevalence of adverse childhood events reported in this sample was high, suggesting greater exposure to adverse childhood events among clients with schizophrenia in comparison with community samples (

7,

8 ). These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that adverse events in childhood are related to subsequent development of a range of mental illnesses, including schizophrenia (

1,

3,

63 ). However, this study goes beyond prior research in this area by documenting relationships between cumulative exposure to adverse childhood events and different functional outcomes.

Our results suggest that adverse childhood events represent risk factors for psychiatric, substance abuse, health, and social functioning problems among adults with schizophrenia, as they do in the population as a whole. Because the primary disorder of schizophrenia is associated with high levels of morbidity and dysfunction in all of these domains, it may be harder to demonstrate the added impact of adverse childhood events on some of the variables assessed, such as poverty and unemployment. Adverse childhood events cumulatively predicted most of the mental health indices (such as presence of PTSD, alcohol or drug use disorders, days of hospitalization, suicidal thoughts, and self-rated mental health). These results are consistent with other studies showing relationships between childhood sexual and physical abuse and psychiatric symptoms in severe mental illness (

2,

5,

9,

10,

11,

12,

64 ). Childhood adversity was also a powerful predictor of physical health outcomes, such as number of physician visits, self-rated physical problems, total number of self-reported physical illnesses, and presence of HIV. These findings extend prior research on the health correlates in adulthood of childhood adversity in the general population (

27,

28,

29,

30 ) to persons with schizophrenia.

Finally, adversity in childhood was a less strong predictor of functional outcomes in this study, predicting criminal justice involvement and homelessness but not poverty, employment status, or global functioning. Homelessness, criminal justice system involvement, and substance use disorders have all been linked to each other and to childhood adversity in the general population. All together, the findings suggest that even among people with an established severe mental illness (schizophrenia), those with higher levels of childhood adversity have significantly worse psychiatric, health, and social functioning than similar individuals with less exposure to such events.

Conclusions

Important implications of this study are that most clients with diagnoses of schizophrenia in the public mental health system are likely to have been exposed to serious adverse events in childhood and that the social and psychological consequences of this exposure include worse health, mental health, and functional outcomes. Exposure to adverse childhood events is associated with elevated rates of comorbid conditions such as alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and PTSD, even though these diagnoses are already elevated in this population. These comorbid disorders have a deleterious effect on the course of illness and may add considerable complexity to treatment management. Tailored interventions to address the adult consequences related to adverse childhood events may be necessary to improve outcomes for many clients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grants R01-MH-50094-03S2, P50-MH-43703, R01-MH-48103-05, P50-MH-51410-02, R24-MH-54446-05, and R01-MH-52872 from the National Institute of Mental Health, by grant UNC-CHJ from the Duke Program on Services Research for People With Severe Mental Disorders, by grant CT DMH from Yale, and by grant EPP97-022 from the Veterans Affairs Epidemiologic Research Information Center. The authors acknowledge the contributions of the members of the five-site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Connecticut: Susan M. Essock, Ph.D., and Jerilynn Lamb-Pagone, M.S.N. Duke University, Durham, North Carolina: Marvin Swartz, M.D., Jeffrey Swanson, Ph.D., and Barbara J. Burns, Ph.D. Durham, North Carolina: Marian I. Butterfield, M.D., Keith G. Meador, M.D., M.P.H., Hayden B. Bosworth, Ph.D., Mary E. Becker, Richard Frothingham, M.D., Ronnie D. Homer, Ph.D., Lauren M. McIntyre, Ph.D., Patricia M. Spivey, and Karen M. Stechuchak, M.S. Maryland: Fred C. Osher, M.D., Lisa A. Goodman, Ph.D., Lisa J. Miller, Jean S. Gearon, Ph.D., Richard W. Goldberg, Ph.D., John D. Herron, L.C.S.W., Raymond S. Hoffman, M.D., and Corina L. Riismandel. New Hampshire: Patricia C. Auciello, M.S., George Wolford, Ph.D., Mark C. Iber, Ravindra Luckoor, M.D., Gemma R. Skillman, Ph.D., Rosemarie S. Wolfe, M.S., Robert M. Vidaver, M.D., and Michelle P. Salyers, Ph.D.

The authors report no competing interests.