Physical activity has the potential to enhance the quality of life for people with serious mental illness. It has been shown to improve physical health and to alleviate psychiatric and social disabilities (

1 ). It has been recommended that physical activity programs be routinely integrated into psychiatric services (

1 ), and individuals with severe mental illness are interested in physical activity as a component of weight management (

2 ).

For physical activity to be promoted, the interests of particular groups need to be considered (

3 ), including preferences for types of activity as well as support and perceived barriers to the activity. This information is available for the general population (

4 ); however, we could not identify any cross-sectional studies that have elicited this information from persons with severe mental illness. This information would assist psychiatric services in planning interventions, communication campaigns, and recreation facilities.

The study presented here assessed physical activity preferences, preferred sources of assistance to promote physical activity, and perceived barriers to physical activity among persons with serious mental illness. In addition, we assessed other psychosocial variables (self-efficacy, beliefs, perceived social support, motivation, and enjoyment) that have been shown to be important influences on physical activity uptake in the general population (

5 ).

Methods

The study involved a cross-sectional survey. Adults receiving treatment for psychiatric illness in the United Kingdom National Health Service and receiving inpatient treatment or outpatient treatment from community mental health centers in southwest London were eligible for the study. Between January and April 2003, presentations describing the study were made to patients at these centers and hospital wards. After the presentation all patients present were invited to joined the study (N=151), irrespective of their psychiatric disorder. For all individuals agreeing to be interviewed the site manager confirmed that the person had the capacity to give written consent. None of those volunteering were refused entry to the study. All volunteers were interviewed in a private room for approximately 20 minutes on a single occasion by a researcher using a structured questionnaire. Questions were read out loud to participants, and the researcher wrote down the responses. Participants were not compensated for their involvement. Participants gave written consent to participate and to provide access to their medical records. Approval of the local ethics committee was obtained. Statistical analyses were carried out by using SPSS version 13.

Demographic characteristics and primary psychiatric diagnosis were extracted from patients' medical records. Physical activity during the previous seven days was reported (

6 ). This measure has shown adequate validity and reliability in this population (

7 ). It was explained to participants that the term "exercise" was used to refer both to structured exercise and to lifestyle activities—for example, walking.

Preferences for physical activity were assessed by asking, "Which of the following types of exercise do you most like to do?" (

8 ).

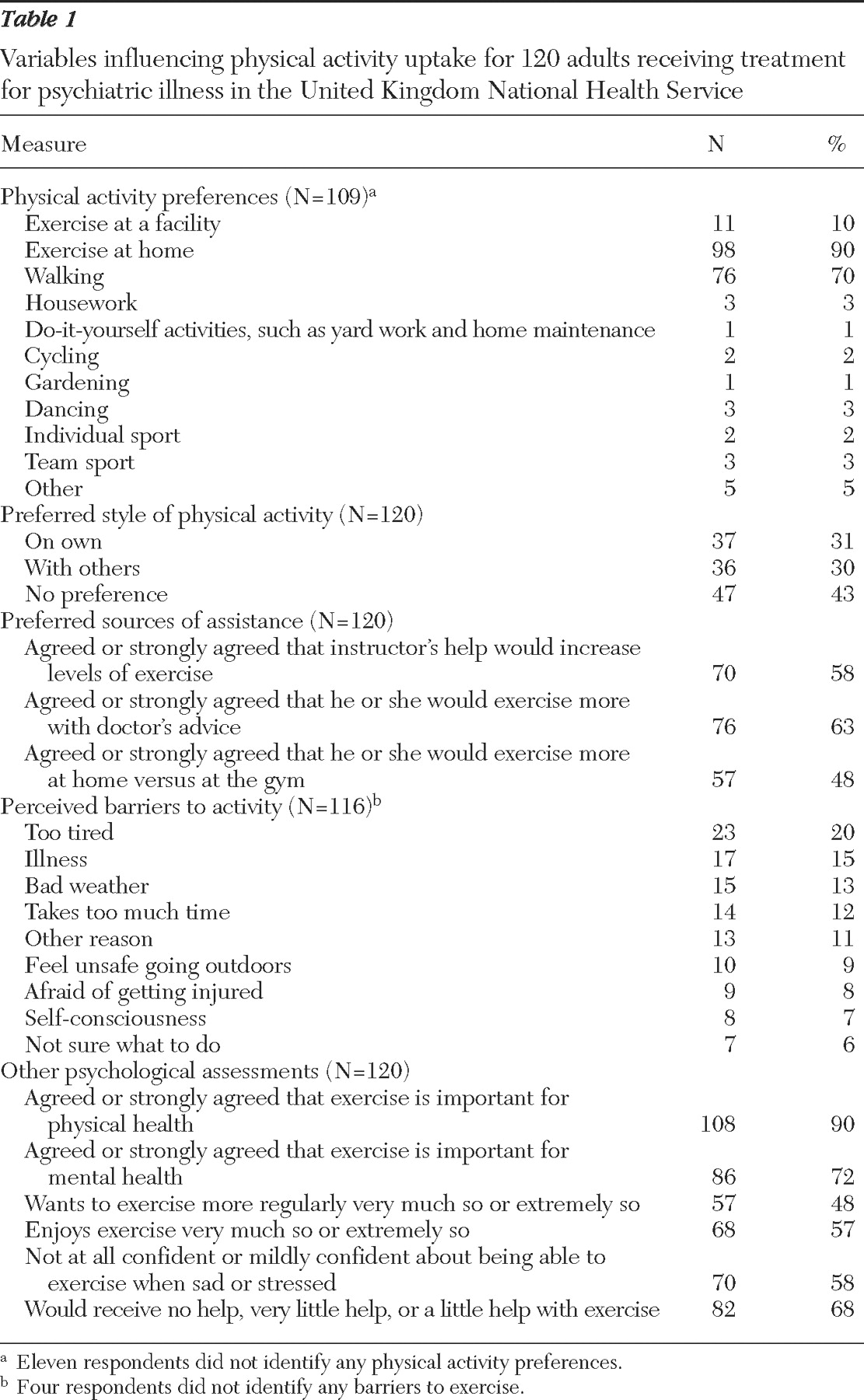

Table 1 shows a complete list. Preferences were also assessed by asking, "Given the choice, would you prefer to exercise on your own, with other people, or don't you have a preference?"

Preferences for assistance were assessed by asking, "How much do you agree with the following statements (strongly disagree=1, disagree=2, neither agree or disagree=3, agree=4, strongly agree=5): (i) I would exercise more if an [exercise] instructor talked through with me what I should be doing, (ii) I would exercise more if my doctor suggested that I should, (iii) I would exercise more at home than at a gym."

The psychological measures were adapted from existing questions (

9 ). Perceived barriers to physical activity were assessed by asking, "Which of the following would you say is the most important reason why you don't do as much exercise as you would like?"—for example, takes too much time or afraid of getting injured;

Table 1 shows a complete list of options. Self-efficacy for exercise was assessed with the question "How confident do you feel about exercising [being able to exercise] when you are feeling sad or stressed?" Possible responses included 1, not at all; 2, mildly; 3, somewhat; and 4, very. Beliefs regarding exercise were determined by assessing level of agreement with the statements "Exercise is very important for my physical health" and "Exercise is very important for my mental health." Possible responses range from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. Social support for physical activity was gauged by asking, "How much help would you get from family and friends if you were to start taking more regular exercise?" Possible responses ranged from 1, no help at all; 2, very little; 3, a little; 4, quite a lot; and 5, a lot. Motivation was assessed by asking, "How much do you want to start taking more regular exercise?" Possible scores range from 1, not at all, to 5, extremely so. Enjoyment was assessed by asking, "How much do you enjoy exercise?" Possible scores are 1, not at all; 2, a little; 3, somewhat; and 4, very much so.

Results

Of the 151 patients invited, 120 patients agreed to be interviewed. Of these a majority were male (70 patients, or 58%), smokers (70 patients, or 58%), single (92 patients, or 77%), unemployed (98 patients, or 82%), and receiving inpatient treatment (80 patients, or 67%). A total of 82 patients (68%) were Caucasian, 27 (23%) were black, six (5%) were Asian, and five (4%) were in another racial or ethnic group. The mean±SD age was 42.6±16.1 years. Sixteen patients (13%) had recently entered the treatment service and a diagnosis had not yet been made. Of 104 participants with a diagnosis, the largest percentage had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (36 patients, or 35%), followed by depression (20 patients, or 19%), bipolar disorder (18 patients, or 17%), schizoaffective disorder (nine patients, or 9%), personality disorder (eight patients, or 8%), and psychosis (five patients, or 5%). The remaining eight patients were diagnosed as having either mania (two patients, or 2%), alcoholism (one patient, or 1%), anorexia (one patient, or 1%), generalized anxiety disorder (two patients, or 2%), monosymptomatic delusional disorder (one patient, or 1%), or acute confusional state (one patient, or 1%). Recommended physical activity levels—at least 30 minutes of at least moderate intensity at least five days a week (

10 )—were achieved by 24 participants (20%). Details of other assessments are given in

Table 1 .

The most popular activity was walking, followed by structured exercise at a facility. The sample was evenly split between preferring individual exercise or group exercise, and more than a third expressed no preference. Almost half agreed or strongly agreed that they would exercise more at home rather than at a gym. A majority agreed or strongly agreed that they would exercise more if they talked with an instructor or were advised to do so by their doctor. The most frequently reported reasons for not exercising were fatigue, illness, and bad weather.

A vast majority of respondents reported that they believed in the benefits of exercise for both physical and mental health and that they enjoyed exercise, but they had little confidence in being able to exercise when feeling sad or stressed and received little, if any, support for exercise from family and friends. Around half reported a high level of motivation to exercise more regularly.

The findings for exercise levels (number of days with 30 minutes of activity) and for the key psychological variables of motivation to exercise, self-efficacy, and social support were assessed for differences according to gender, age, smoking status, treatment setting, diagnosis, employment status, and marital status. When regression analysis was performed, we found no significant differences in reports of exercise levels, motivation, or social support according to these characteristics. However, self-efficacy for exercise was significantly lower among women compared with men, among patients with depression compared with those with other disorders, and among outpatients compared with inpatients. When a forced-entry regression analysis was performed, several factors remained associated with self-efficacy: gender ( β =.43, p=.042), outpatient versus inpatient ( β =.57, p=.011), and diagnosis ( β =.76, p=.011).

Discussion

Consistent with previous findings (

1,

11 ), participants tended to be more sedentary than the general population and walking was the most common activity. There was a high level of interest in being more active, and a vast majority reported that they believed in the benefits of exercise and enjoyed exercise. This should be grounds for optimism in developing physical activity opportunities for this population. However, participants tended to report very little confidence in their ability to exercise when feeling sad or stressed and little, if any, social support for exercise. Lack of regular social contact appears to be a common correlate of inactivity in this population (

11,

12 ), and low self-efficacy is one of the strongest determinants of inactivity in general (

5 ).

Evidently, physical activity interventions for the psychiatric population need to find ways to bridge the gap between high levels of interest and low levels of exercise. This might involve increasing social support. Our findings suggest that, consistent with findings in the general population (

8 ), this population values the support of health professionals. Self-efficacy for exercise may need to be enhanced by, for example, using cognitive-behavioral strategies (

4 ). In addition, our findings suggest that such interventions may be especially needed among women, outpatients, and those with depression. Moreover, interventions may be more beneficial by being integrated with recovery and peer-support approaches to psychiatric rehabilitation (

13,

14 ) that embrace health promotion (

15 ).

Interventions will need to address barriers to the uptake of exercise, such as fatigue and illness, which have been reported more frequently among persons with severe mental illness than in the general population (

4 ), and interventions may need to consider other barriers (

12 ) not assessed in the study presented here. Physical activity interventions for persons with severe mental illness need to be tailored to individual preferences—for example, toward the mode of exercise and for exercising alone versus with others. Education may be beneficial concerning opportunities for leisure-based and lifestyle activity on the basis of personal preferences, as opposed to prescribed and structured exercise regimens (

16 ). The results presented here provide support for interventions focusing on walking, and encouraging an existing activity may be a simpler task than trying to initiate a novel behavior (

16 ). This study was limited in that it was a cross-sectional study with a relatively small sample and it used several measures that have not been validated. Prospective studies of preferences and barriers are required with larger samples of patients and with subgroups of patients—for example, with persons with severe depression.